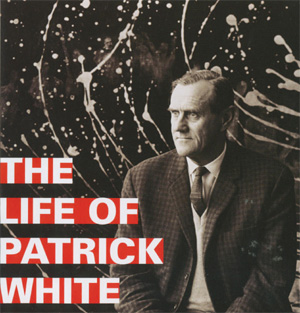

To Canberra on 12 April for the opening of a new travelling exhibition, The Life of Patrick White.

To Canberra on 12 April for the opening of a new travelling exhibition, The Life of Patrick White.

First, though, a quick dash that morning to Sydney for a meeting with Bernadette Brennan and Hilary McPhee. The three of us have been judging this year’s National Biography Award. We met in the small but spectacular Shakespeare Room at the Mitchell Library. First we shortlisted six of the dozen hitherto longlisted titles – biographies, autobiographies, memoirs. Then, after an unElizabethan lunch of shaslicks and chicken wraps, we chose our winner, who will be named and fêted and enriched by $25,000 at a ceremony on Monday, 14 May.

Then, rather glad to be able to read something other than biography for the first time in two months, I flew to Canberra rereading Persuasion for the first time in years.

The National Library’s congenial downstairs theatre soon filled, and James Spigelman (Chair of the National Library) – with a pleasing lack of ceremony (rare in the national capital; in any capital, for that matter) – introduced our two speakers.

Barbara Mobbs – Patrick White’s long-time literary agent, and now his literary executor – rightly came first. But for her the National Library and the State Library of New South Wales (partners in this venture) would struggle to mount a major exhibition, because of the paucity of manuscripts and memorabilia. Mobbs’s remarkable and laudable decision to ignore White’s express wish that all of his surviving notebooks and manuscripts (including the unfinished The Hanging Garden, which Peter Conrad reviews in our April issue) should be destroyed led ultimately – almost two decades after his death in 1990 – to their being transferred the most appropriate cultural repository in the country – the National Library of Australia.

When Mr Spigelman referred to this agential refusal – to coin a term – there was lengthy applause. Mobbs, always direct and impressively dry, began her short, witty, stylish speech in Piafian style – ‘I have no regrets.’ In passing James Spigelman had described Patrick White as curmudgeonly, but Mobbs was having none of this. She spoke of White’s kindness, good humour, and immense loyalty to friends – and to the several charities he quietly supported. She said that she enjoys writing cheques to the four principal beneficiaries of White’s estate, including the Smith Family and the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Her account of White’s ignorance of technology made me feel like less of a luddite. Once, having heard of the miracle of faxing, he asked Mobbs to send a letter to London. He was bamboozled next time they met when she returned the letter. But he’d asked her to fax it! She reminisced about their shopping expeditions, when she was often mistaken for his daughter.

Mobbs recalled White’s famous penchant for the telephone. When he asked her to become his literary executor, she said it wouldn’t be very different from her previous role – except that she wouldn’t be on the phone to him for six hours a week.

Then came Judy Davis – whose role as Dorothy in Fred Schepisi’s The Eye of the Storm rightly won her another AFI award, or an AACTA, as they are now called. Extemporising freely, with funny sawing gestures, she reminded us of her inspired Judy Garland in the miniseries that won her an Emmy. Davis first read White as an eighteen-year-old, in Perth. This was in 1973, soon after he had won the Nobel Prize. The book was Riders in the Chariot – a transformative experience for her. (Here I recalled my own introduction to White that same year – The Aunt’s Story in my case: so astonishing and transcendent in Part One that I had to put it aside and compose myself for a while before resuming it.) Davis was awed by the book – ‘Suddenly I didn’t feel alone.’

Afterwards, there was time only for a quick look at the exhibition, which remains in Canberra until June before moving on to the State Library of New South Wales on 13 August. It is a large, detailed, funny, poignant exhibition. I was impressed by the letters, the manuscripts, the photographs, the dust jackets – less so by the several pictures White donated to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The desk is there (a replica of the one Francis Bacon made for him in London); above it Ian Fairweather’s Gethsemane, which he donated to in 1974 (AGNSW, not uncontroversially, sold it two years ago to help fund its acquisition of Fairweather’s The Last Supper). Among the memorabilia are his typewriter and beret and spectacles – and a certain medal, in its own case.

Later the National Library hosted a dinner at Water’s Edge. I drew a good table, with Wendy Whiteley and actors Kate Fitzpatrick and Angela Punch McGregor – and we had an immoderately good time. Kate and the Whiteleys look to be having a similarly good one with Patrick White and Manoly Lascaris in the 1980 photograph by William Yang that hangs in this highly recommended exhibition.

Peter Rose

Editor, Australian Book Review

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.