Language Column

The Dictionary People: The unsung heroes who created the Oxford English Dictionary by Sarah Ogilvie

My edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (1979) defines ‘dictionary’ in two ways: ‘1. A book dealing with the individual words of a language … so as to set forth their orthography, pronunciation, signification and use … arranged, in some stated order, now, in most languages, alphabetical …’; ‘2. By extension: A book of information or reference on any subject or branch of knowledge, the items of which are arranged in alphabetical order …: as a Dictionary of Architecture, Biography, Geography … etc.’

... (read more)The Oxford Guide to Australian Languages edited by Claire Bowern

Kado Muir – a Ngalia man – will never be able to have another conversation in his mother tongue. He tells the story of witnessing each of his elders dying and, in the process, his language. Successively, he had fewer and fewer people to communicate with. In the case of his language community, younger contemporaries shifted to English as the language exerted its colonial power – until at last Kado Muir became the last speaker of Ngalia.

... (read more)When I told a friend I was thinking of writing an essay on pre-Hispanic literature he said, ‘Forget it. You’d have to go to university to find out how to write an essay. Why don’t you write about your Christmas holidays?’ So perhaps it’s polite to warn readers that the following words, observations, and ideas are derived solely from personal experience, reading and reflection. I am a genuine lay person, shamelessly uneducated, having left school at fifteen and not found the time (or funds) to return since.

... (read more)Cheerio Tom, Dick and Harry: Despatches from the hospice of fading words by Ruth Wajnryb

This is a book about words that are on their way to the dictionary cemetery where they will be stamped with the labels ‘archaic’ or ‘obsolete’. Of course, unlike us, these dying words will achieve a kind of eternity through being permanently displayed in dictionaries, but the time will come when no living person possesses them as part of their actual speech. Ruth Wajnryb proposes that a hospice should be set up to provide sanctuary and comfort for these weary and largely forgotten lexical bits and pieces, a ‘hospice of fading words’.

... (read more)In the introduction to their excellent collection of essays, Class in Australia (2022), Jessica Gerrard and Steven Threadgold note the eclipsing of the word class in our public discourse. Other descriptive markers are more commonly used, words such as disadvantage (by scholars) and bogan (in popular culture). In my own work on the Australian English lexicon, I have been intrigued by the contemporary language of class. The words we choose to use when talking about class can tell us much about changing popular perceptions.

... (read more)In his concession speech on election night, after a perfunctory Acknowledgment of Country and a fulsome acknowledgment of Australia’s defence personnel, past and present; after hymning our ‘functioning’ democracy with reference to Ukraine, and intimating that without him we imperil ourselves; after mentioning the ‘great upheaval’ of recent years but failing to use the words pandemic, floods, lockdown, bushfire, or climate change; and after reassuring us that he still believes in miracles, outgoing Prime Minister Scott Morrison declared that ‘the one thing’ he had ‘always counted on’ was ‘the strength and resilience and character of the Australian people’.

... (read more)Each federal election brings with it a bunch of promises, attacks, blunders, and unpredictable moments. During the recent federal election we had Anthony Albanese’s ‘gaffe’, Scott Morrison’s undercooked chicken curry, and #JoshKeeper. As usual, the intrepid (and long-suffering) lexicographers and language watchers were hard at work monitoring the language of the campaign.

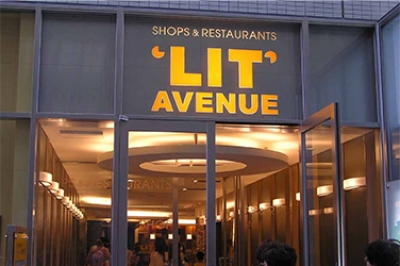

... (read more)At a dinner party recently, the conversation turned to how our language gives away our age. No more so than in the use of slang, proposed one guest, who suggested that each person’s use of slang, like a favourite pop song, is frozen in time from their teenage years. Take, for example, terms for something considered ‘wonderful’. The theory goes that if someone still says swell, tickety-boo, or snazzy, chances are they were teenagers during World War II. Boomers, those born after the war until the mid-1960s, are the most likely to use super duper, wild, or far out. Someone nearing fifty, a Gen Xer, is probably the most likely to say brill or wicked. Millennials and Gen Z would be the ones saying crunk, wig, and slaps.

... (read more)Kingdom of Characters: A tale of language, obsession, and genius in modern China by Jing Tsu

Picture, poem, or puzzle? The Chinese written character has been one of the most enduring obstacles to and catalysts for intercultural appreciation. When, in the early decades of the nineteenth century, the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel wanted to demonstrate the relative backwardness of Oriental thought, he could find no better exhibit than the form of its writing. Attached as it was to ‘the sensuous image’, the putatively pictographic Chinese character forfeited access to the conceptual abstraction that afforded European thinkers their passports to the ‘free, ideal realm of Spirit’.

... (read more)A deadpan comedian maintains a straight face or an even tone while delivering ridiculous content. As a performance of humourlessness that makes people laugh, deadpan registers tensions in contemporary culture. Comedy is among the most popular modes of entertainment and social commentary: the Melbourne International Comedy Festival, for example, is Australia’s largest ticketed cultural event, with attendances of up to 770,000. But over the past few years, criticism of comedy’s traditional reliance on stereotypes and its misogynistic and homophobic industry conditions has intensified as high-profile comedians (Bill Cosby, Louis C.K.) were denounced or tried for sexual misconduct and as a new generation of ‘woke’ comedians have engaged with a resurgent cultural earnestness, often disparaged as ‘PC humourlessness’.

... (read more)