Literary Studies

Shakespeare is not a hoax, but he is hoaxy. The field of Shakespeare studies is brimming with fibs and fables. There are the ‘Shakespeare heretics’ who have posited, on flimsy evidence, that Henry Neville, Francis Bacon, Edward de Vere, or someone else was the ‘secret author’ of William Shakespeare’s works. There have been plenty of frauds and near-frauds on the ‘orthodox’ side of Shakespeare studies as well. A.L. Rowse, for example, simply made up an elaborate back story for the ‘Dark Lady’ of Shakespeare’s sonnets.

... (read more)This week on The ABR Podcast, we feature a special essay by biographer Nadia Wheatley titled ‘Liars, inventors, embroiderers: Rewriting the life and myth of Charmian Clift’.

... (read more)What does a biographer do when she discovers she has something wrong? I am not talking about a misinterpretation, but missing a great big whopping fact …

In this case, the new information did not concern my subject directly, but her mother. Nevertheless, it has caused me to rewrite parts of both the life and the myth of Charmian Clift.

... (read more)The Making of a Poem: Eleven Australian poets talk about their craft by Rosanna McGlone

Extraordinary though it is, narrative film has its limitations. It is a truism of film criticism, for instance, that biopics of writers are usually at their weakest when representing the process of writing. It is an understandable problem. How, in the dynamic medium of film, is one to represent the (in)action of writing, which is largely solitary, motionless, and internal? In biopics of poets such as Syliva Plath and Dylan Thomas, the process of composing poetry is usually rendered in a Terrence Malick–like montage of soft-focus, shallow depth of field, handheld shots meant to signify the numinous, visionary experience of poetic inspiration. This cinematic convention is more or less nonsense. Biopics of writers are also largely indifferent to issues of technique – the slow, uneconomical labour of dealing with language as a medium. Who cares if that verb in the last line should be a gerund?

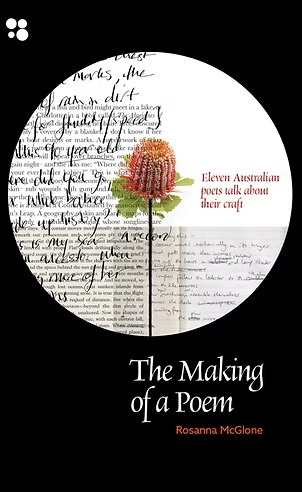

... (read more)Some literary biographies are best known for their gestation – or malgestation. Some authors, we might go further, should have a big sign around their neck – noli me tangere. Muriel Spark is one of them. Her voluminous archive, lovingly tended all her life, is full of booby traps. Twice she went into battle with biographers: first Derek Stanford, a former lover; then Martin Stannard, whose biography of Evelyn Waugh she had admired.

... (read more)The Collected Prose of Sylvia Plath by Sylvia Plath, edited by Peter K. Steinberg & Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark

For seven years after her 1963 burial, Sylvia Plath lay in an unmarked grave near St Thomas the Apostle Church in Heptonstall, West Yorkshire. The gravestone, when it came, bore her birth and married names, Sylvia Plath Hughes, the years of her birth and death, and a line from Wu Cheng-en’s sixteenth-century novel Monkey King:Journey to the West: ‘Even amidst fierce flames, the golden lotus can be planted.’

... (read more)On Patrick White’s Dilemmas: A personal essay by Vrasidas Karalis

‘Lonely Country’ is the term Arnhem landers use for empty or uncared-for places. Sometimes the custodians have died. In other cases, the land is simply too difficult to get to or inhabit. Whatever the reason, Lonely Country brings sadness. There is no one to burn the bush or manage it; no one to call out to the spirits of the old people who remain on their Country, isolated from the living.

... (read more)In 1588, with England facing the threat of Spanish invasion, Elizabeth I visited her troops assembled at Tilbury to deliver some rousing words: ‘I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.’ This assertion, the idea that the body politic was eternal and existed in a sacred realm beyond historical time, was ideally suited to a moment of national crisis. But rhetorical force notwithstanding, Elizabeth was propounding a fiction. In Shakespeare’s Tragic Art, Rhodri Lewis explores how William Shakespeare was able to use the tragic form to interrogate those ‘fictions of order, stability, and perpetuity’ that humans deploy in their desire to make sense of a random universe. Beginning with Titus Andronicus and ending with Coriolanus, Lewis shows how each play is a response to a particular set of aesthetic challenges. Shakespeare’s motivations lay in exploring the possibilities of the tragic genre. Through plays as various as Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, and King Lear, he explored ‘never-settled notions’ of what tragedy could achieve.

... (read more)Inconvenient Women: Australian radical writers 1900-1970 by Jacqueline Kent

Was Katharine Susannah Prichard one of those present at the first meetings of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), or not? Did she or didn’t she later pass intelligence to the Soviets, as charged by historians of ASIO Desmond Ball and David Horner? What difference would it have made to have had Lesbia Harford’s full queer oeuvre before the Australian public when it was written? Why didn’t Dymphna Cusack join the CPA if, as this book asserts, her politics were just as far left as Frank Hardy’s? How aware was Eleanor Dark of First Nations activism when writing The Timeless Land (1941)? Politics sit at the heart of Australian literary history, but a raft of questions remain for contemporary readers.

... (read more)Stranger than Fiction: Lives of the twentieth-century novel by Edwin Frank

What is the twentieth-century novel? asks Edwin Frank in Stranger than Fiction. What it is not, he begins, is the nineteenth-century kind. This doesn’t mean he argues from a merely negative premise; rather, he’s attempting to wrest the discussion from certain warping assumptions. The very notion of periodisation by centuries – a ‘convenient, newly minted unit’, writes Frank, ‘larger than a lifetime, conformable to the memory of the nuclear family and designed to connect past to future in the developing narrative of human history’ – is itself a product of the nineteenth century.

... (read more)