Australian History

Sex and Savagery in the Good Colony: South Australia 1836-1901 by Julie Marcus

With a title that grabs the attention of readers and a subject deserving of a wide readership, I eagerly awaited Julie Marcus’s Sex and Savagery in the Good Colony: South Australia 1836-1901. As an anthropologist who specialises in depictions of race, gender, and sexuality, Marcus is well placed to survey the historical sources and provide fresh insights into early cross-cultural relations, frontier violence, the mistreatment of Aboriginal women, as well as the enduring impacts of colonialism in South Australia. Unfortunately, red flags appeared in short succession.

... (read more)In 1996, an Age poll found that seventy-six per cent of Australians wanted their country to become a republic. The issue had been rapidly gaining momentum since the early 1990s. The creation of the Australian Republican Movement (ARM) in 1991, and the active championing of the issue by Prime Minister Paul Keating, turned a fringe issue of the 1980s into a realistic prospect.

... (read more)This week, on The ABR Podcast, Patrick Mullins reviews Hawke PM: The making of a legend by David Day. Approaching Day’s second volume of the Hawke biography, Mullins asks: ‘how much more can there be to say?’

... (read more)There is a fine tradition in Australia of two-volume prime ministerial biographies. John La Nauze on Alfred Deakin (1965), Laurie Fitzhardinge on Billy Hughes (1964, 1979), John Edwards on John Curtin (2017, 2018), Allan Martin on Robert Menzies (1993, 1999), Jenny Hocking on Gough Whitlam (2009, 2012): all are insightful and enduring accounts of significant figures who exerted deep influence on the country.

... (read more)Defiance: Stories from nature and its defenders by Bob Brown

In a dark age on a burning planet, radical hope is not an easy assignment, but every decade or thereabouts, Bob Brown invites Australians to give it a crack. His Memo for a Saner World (2004) was followed by Optimism (2014), and his new release, Defiance, opens as a redux of both, with the cinematic story of the environmental campaign that changed Australia’s political contours.

... (read more)Reframing Indigenous Biography edited by Shino Konishi, Malcolm Allbrook, and Tom Griffiths & Deep History edited by Ann McGrath and Jackie Huggins

The growth in understanding of the tens of thousands of years of this continent’s pre-colonial and post-colonial Aboriginal history has been one of the great intellectual achievements of postwar Australia. But if these two collections of essays are any guide, there are reasons to be gravely concerned about the future of this field of knowledge.

... (read more)The genocide of the First Peoples of Tasmania, concentrated within a brief, sixty-year span from 1815-75, was an incalculable tragedy that destroyed a remarkably adaptable and ecologically sustainable group of nations who occupied the island for at least 40,000 years. The rapid destruction of Aboriginal Tasmania in a colonial environment that was rapacious and profoundly racist meant that there was next-to-nothing left that might allow us to understand how they saw themselves, or the nature of their social structures and customs, and the belief systems of their world. This is especially tragic for the descendants who have sought to affirm their Aboriginal identity in the face of the ignorance and self-satisfied indifference of the immigrant society.

... (read more)Mark McKenna’s The Shortest History of Australia is the latest offering in Black Inc.’s Shortest History series (now nearing twenty titles). Combining erudition and expertise with good writing and respect for readers, the books aim to be more than a primer or a simple precis of common knowledge. Rather, the challenge of length imposed by the publisher and heralded in the title is generative for the history told. In both the text and in ensuing publicity, authors explain and justify how they tackled the task.

... (read more)Our Story: Aboriginal Chinese people in Australia edited by Zhou Xiaoping

It is deeply sobering to be writing about the depth of the history of multicultural Australia only days after rallies against immigration have been held and in the midst of a palpable and disturbing negative response to non-white immigration. There are echoes of the shameful twentieth-century White Australia policy. Far from being a recent phenomenon, multiculturalism has been an integral aspect of Australian society since European settlement in the late eighteenth century. This collection, edited by the artist Zhou Xiaoping, is the outcome of a three-year research project and is the companion monograph for Our Story: Aboriginal Chinese people in Australia, a free, ground-breaking exhibition currently at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra that will run until late January 2026.

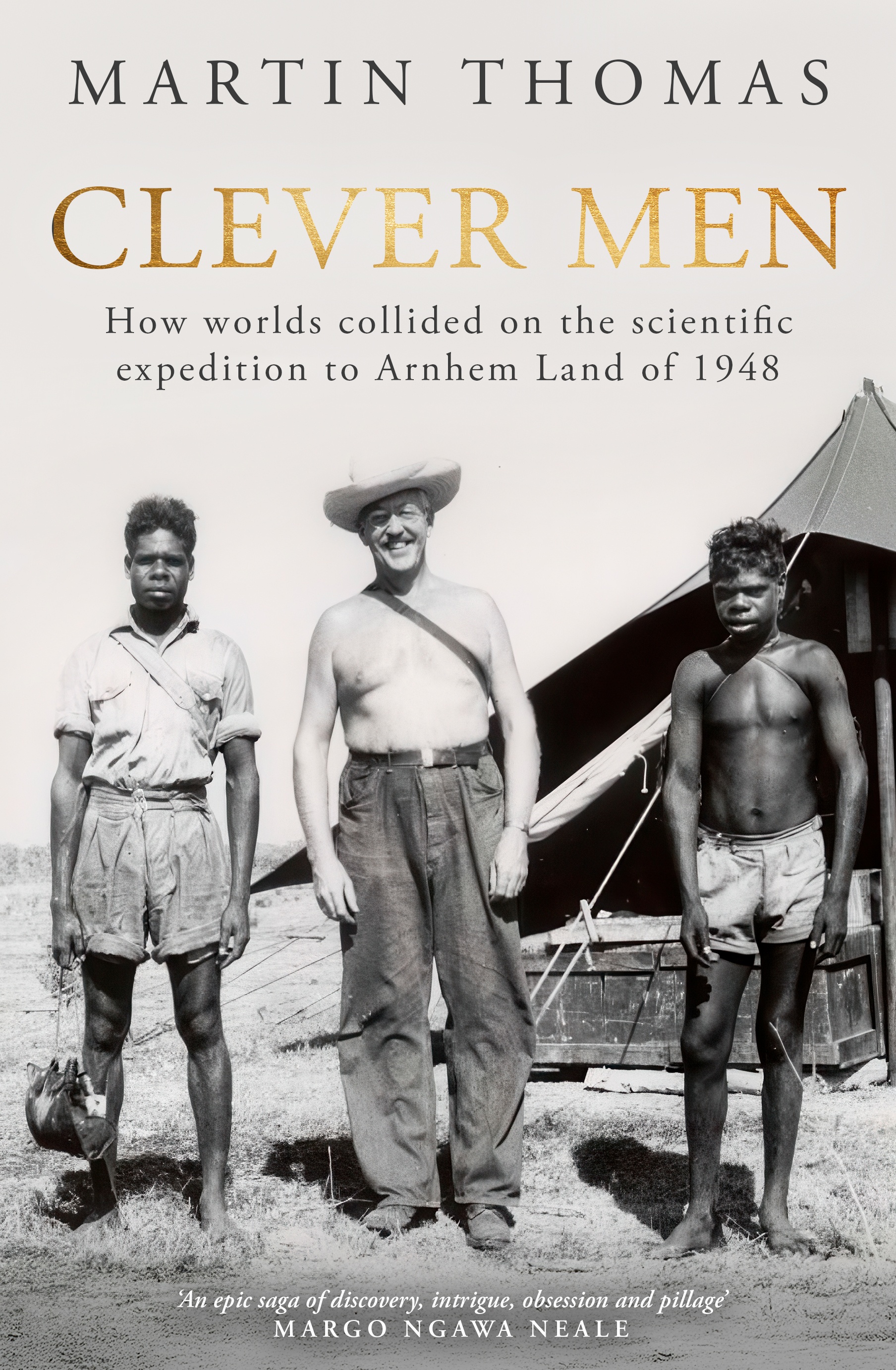

... (read more)Clever Men: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948 by Martin Thomas

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

... (read more)