Theatre

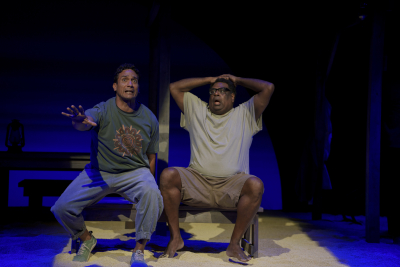

On the opening night of Dear Son at Belvoir, director and co-adaptor Isaac Drandic takes to the stage before the performance. One of the cast members is ill; on short notice, Drandic will play his role. Don’t expect a star turn, he warns.

... (read more)To judge by much of this Melbourne Theatre Company (MTC) production of Much Ado About Nothing, you might think that Shakespeare had written not a tragicomedy but a farce – and a poor farce at that. Director Mark Wilson – renowned, the program notes tell us, for his ‘radical’ adaptations of Shakespeare – pushes so hard at the comedy buttons that ch ...

Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca (1938) opens with one of the most iconic lines in literature (and, thanks to Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 adaptation, one of the most iconic lines in cinema): ‘Last night I dreamed I went to Manderley again.’

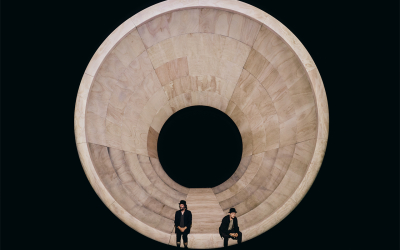

... (read more)In his Broadway debut, sexagenarian Keanu Reeves has reunited with Alex Winter – his co-star from the Bill & Ted film trilogy (1989, 1991, 2020) – for Jamie Lloyd’s bold, minimalist production of Samuel Beckett’s classic. Hollywood stars seeking to prove their mettle on the stage can wrong-foot fans, opting for experimental fare, but this tendency is strangely fitting in Waiting for Godot, a play devoid of traditional exposition, in which confusion reigns supreme.

... (read more)In her classic work of speculative fiction ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’ (1973), Ursula Le Guin forces us to ask what – or who – we are prepared to sacrifice in order to build our utopias. Le Guin describes Omelas as a place of great beauty and happiness. A place that is joyous and ordered, that needs no kings. The people of Omelas are ‘mature, intelligent, passionate’, and there is no grief or misery in their lives. Crucially, Le Guin invites her readers to contribute to the imagining of this utopia, thereby implicating us in the substantial cost of building and maintaining it. As the story reveals, the bliss of Omelas is founded on the suffering of a starved and neglected child locked in a ‘foul-smelling’ underground closet. The child begs and screams, ‘Please let me out. I will be good!’

... (read more)You can make the case that Othello’s handkerchief is the most consequential prop in all of Shakespeare. Yorick’s skull and Macbeth’s floating dagger are more iconic, but neither is integral to the action of the plays in which they feature. The handkerchief, on the other hand, really is the whole of the tragedy of Othello.

... (read more)Look out – here comes Cassandra. Her hair falls long and loose with a braid running through it: part classical heroine, part bohemian drifter. She could be a warrior maiden or the lead singer of an indie rock group. Fake-vintage band T-shirt, gold metallic miniskirt cut like the flaps of ancient armour, and the detail that unsettles the image: a large shopping bag she schleps from scene to scene.

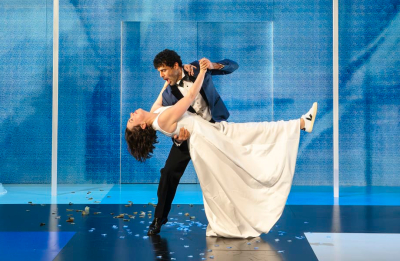

... (read more)What image does Romeo and Juliet conjure for you? How high is your balcony? In Shakespeare’s play, vertical distance is a nod to the Petrarchan courtly love conventions that placed the lady on a pedestal. But, like a lot of conventions, Shakespeare calls up this one only to implode it.

... (read more)Publicity notes for The Orchard outline the questions that provoked Pony Cam’s loose adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard (1904): ‘You’ve inherited a redundant cherry orchard, a crumbling climate, a failing economy and the final play written by Anton Chekhov. What will you salvage? Will you survive the adaptation?’ As far as this audience member is concerned, the answers to those questions are indisputable: ‘Nothing’ and ‘No’.

... (read more)