2018 Arts Highlights of the Year

To celebrate the year’s memorable plays, films, concerts, operas, ballets, and exhibitions, we invited twenty-nine critics and arts professionals to nominate some personal favourites. We indicate which works were reviewed in ABR Arts and when.

Gabriella Coslovich

‘A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us,’ Franz Kafka famously wrote. Film is equally capable of slashing through the ice – or, in this case, the frozen sea of ‘compassion fatigue’ – as Irish artist Richard Mosse shows with his harrowing video work Incoming (2015–16), the standout, for me, of the National Gallery of Victoria’s inaugural Triennial. Mosse flips the intended use of an enemy-seeking, thermal-imaging military camera and uses it to track the perilous flight of refugees in ghostly black and white. The result is a mesmerising work about the crisis of our times.

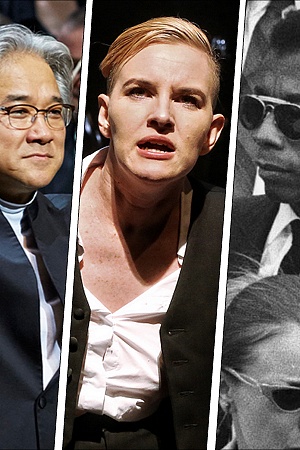

Melbourne playwright Patricia Cornelius’s adaptation of Federico García Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba, staged by the Melbourne Theatre Company, was equally pertinent. It is a superbly cast and chilling re-imagining of Lorca’s tragic tale about gender and power, set in the oppressive heat of outback Western Australia, with a mining fortune at stake.

The cast of The House of Bernarda Alba (photo by Jeff Busby)

The cast of The House of Bernarda Alba (photo by Jeff Busby)

Humphrey Bower

My theatrical highlight of 2018 was Ivo van Hove’s epic multimedia adaptation of Shakespeare’s Kings of War at the Adelaide Festival (ABR Arts, 3/18), featuring Hans Kesting’s deadpan, Keaton-like Richard III. Also at the Festival was the musical performance that moved me most: Jochen Sandig and Sascha Waltz’s immersive staging of Brahms’s (aptly retitled) Human Requiem (ABR Arts, 3/18).

My dance highlight was at Perth Festival: Belgian choreographer Damien Jalet and Japanese sculptor Kohei Nawa’s mysterious, chthonic Vessel. The visual art installation that most absorbed me was also at the Festival: Lisa Reihana’s vast scrolling panoramic video work Emissaries. My opera highlight was WASO’s concert performance of Tristan und Isolde with Stuart Skelton and Gun-Brit Barkmin, conducted by Asher Fisch (ABR Arts, 8/18), closely followed by Lost and Found’s playful, provocative staging of Charpentier’s Actéon at the UWA Aquatic Centre. Finally, the film that most affected me was BPM (Beats Per Minute), Robin Campillo’s visceral account of AIDS activism in 1990s Paris (ABR Arts, 5/18).

Gun-Brit Barkmin in Tristan und Isolde (West Australian Symphony Orchestra)

Gun-Brit Barkmin in Tristan und Isolde (West Australian Symphony Orchestra)

Anwen Crawford

Kamila Andini’s The Seen and Unseen, which screened in competition at Sydney Film Festival, is a tonally mysterious, formally assured drama set in Bali. It explores choreography, animism, and dreams in its depiction of twin siblings. Andini, who has completed two feature films, is a director to watch; she elicits terrific performances from her two child leads, Ni Kadek Thaly Titi Kasih and Ida Bagus Putu Radithya Mahijasena – this in a year of outstanding turns by young actors. Thomasin McKenzie, in Debra Granik’s Leave No Trace, was preternaturally wise as the daughter of a traumatised US army veteran. Thomas Gloria, in Xavier Legrand’s Custody, vividly embodied the anxiety, fear, and grief of a young child living in the shadow of a physically abusive parent. On a lighter note, the young cast members of Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird – including Saoirse Ronan, Lucas Hedges, and Beanie Feldstein – were, by turns, comic and poignant in their ensemble evocation of suburban teenage life (ABR Arts, 2/18).

Promotional image for The Seen and Unseen

Promotional image for The Seen and Unseen

Michael Shmith

At the end of 2017, and too late for last year’s highlights, I marvelled at Opera: Passion, Power and Politics at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (ABR Arts, 11/17). This extraordinary collaboration between the V&A and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, was brilliantly achieved and a miracle of compression: just seven operas by seven composers, each work premièred in a major European city, from 1642 to 1934. Not only did this immersive retrospective display operatic history, it ensured it was heard. The catalogue was just as great. In Melbourne, I particularly liked Victorian Opera’s pioneering production of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell (the French version) in its first staging in Australia since 1876 (ABR Arts, 7/18). Bravo to VO’s artistic director and conductor, Richard Mills.

The NGV’s exhibition of works from the Museum of Modern Art, New York, was exhaustive and exhausting, but I wouldn’t have missed it for quids.

The cast of William Tell (Victorian Opera)

The cast of William Tell (Victorian Opera)

Zoltán Szabó

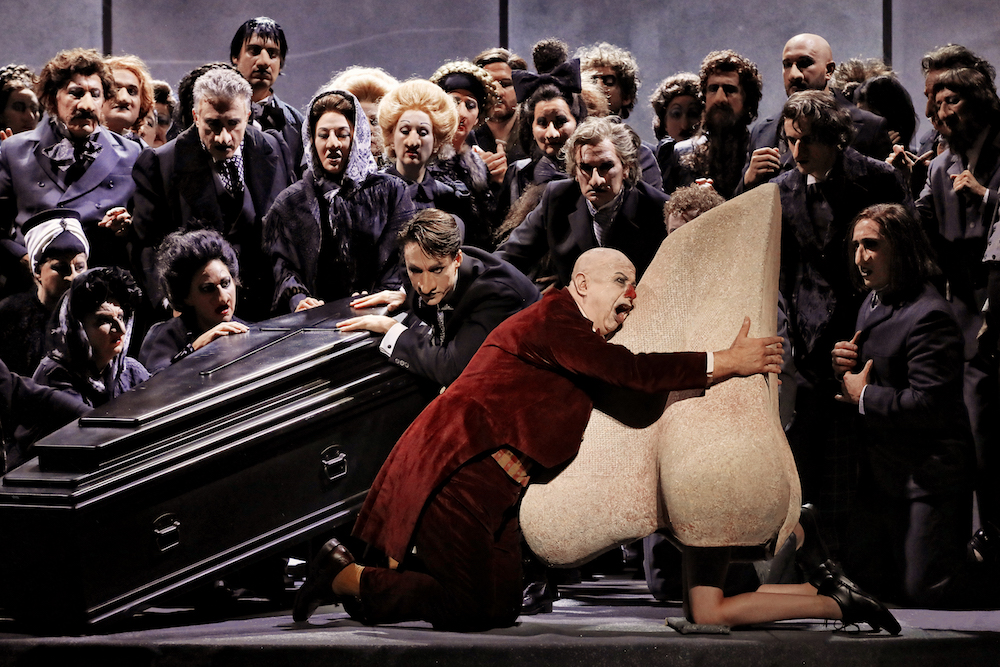

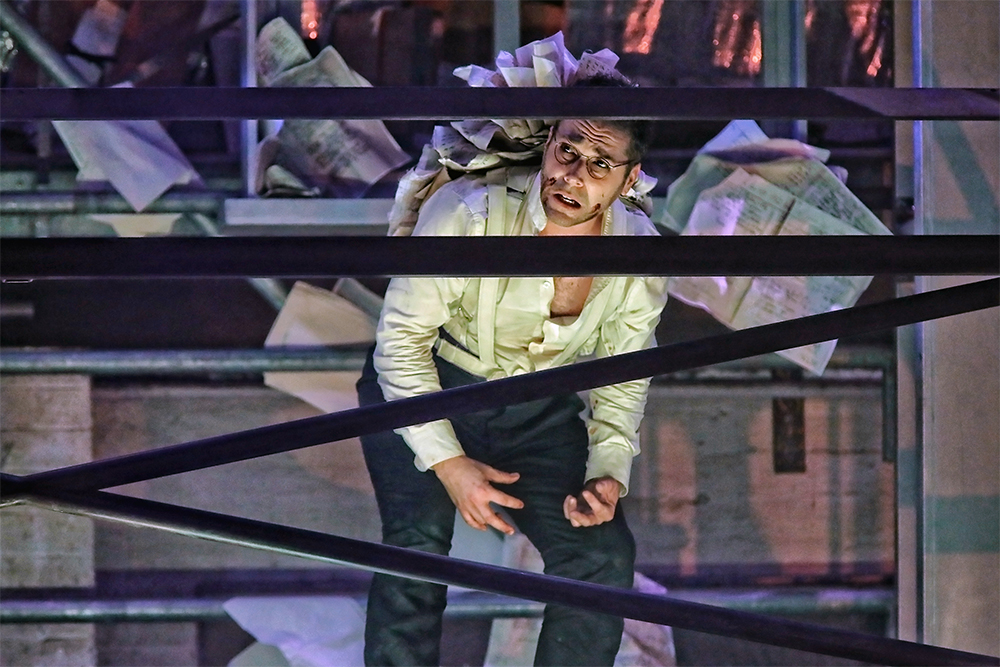

It seems incredible that The Nose, a major opera by Dmitri Shostakovich (his first, in fact), only received its Australian première in 2018 (ABR Arts, 2/18). This production marked the first return of Barrie Kosky to Opera Australia in almost twenty years. Are we so rich in talent, one wonders? This was a celebration of boundless artistic imagination; the delights of this grotesque and quirky story and music splendidly brought to the fore by an outrageously grotesque and quirky production.

A very different artistic and truly cathartic experience was on offer in the latest opus by Hungarian film director, Ildikó Enyedi, On Body and Soul (ABR Arts, 5/18). The metaphorically rich, stunning images of a doe and a stag in the snowy forest were an integral part of a tender love story placed in the unlikely and brutal background of a slaughterhouse.

Martin Winkler and the cast of The Nose (Opera Australia)

Martin Winkler and the cast of The Nose (Opera Australia)

Diana Simmonds

It’s impossible to go past Sydney Theatre Company’s The Harp in the South as the outstanding theatre production of 2018 (ABR Arts, 8/18). Adapted by Kate Mulvany from Ruth Park’s novels, the two-part epic ran to six hours. The published play calls for a ‘large cast’. Nineteen fine actors portrayed the Irish Catholic family and a muddledom of neighbours across the generations. After the success of The Seed, Medea, and Jasper Jones, Mulvany demonstrates astonishing maturity and confidence with The Harp, capturing its intimacy and sprawl, the colour and shape of characters, and the all-important humour. Assembling a top creative team, STC boss Kip Williams cemented his place as one of the best directors with a production that satisfied in every way.

Jack Ruwald, Anita Hegh, and Jack Finsterer in The Harp in the South (photo by Daniel Boud)

Jack Ruwald, Anita Hegh, and Jack Finsterer in The Harp in the South (photo by Daniel Boud)

John Allison

‘Must the winter come so soon?’ is something nagging at us all in the northern hemisphere right now, but such thoughts are eased slightly by memories of this aria – the most celebrated music in Samuel Barber’s 1958 opera Vanessa – being sung on a summer evening at Glyndebourne. The first professional British staging of Barber’s wonderful opera was a highlight of the year, thanks not least to Keith Warner’s psychologically probing production.

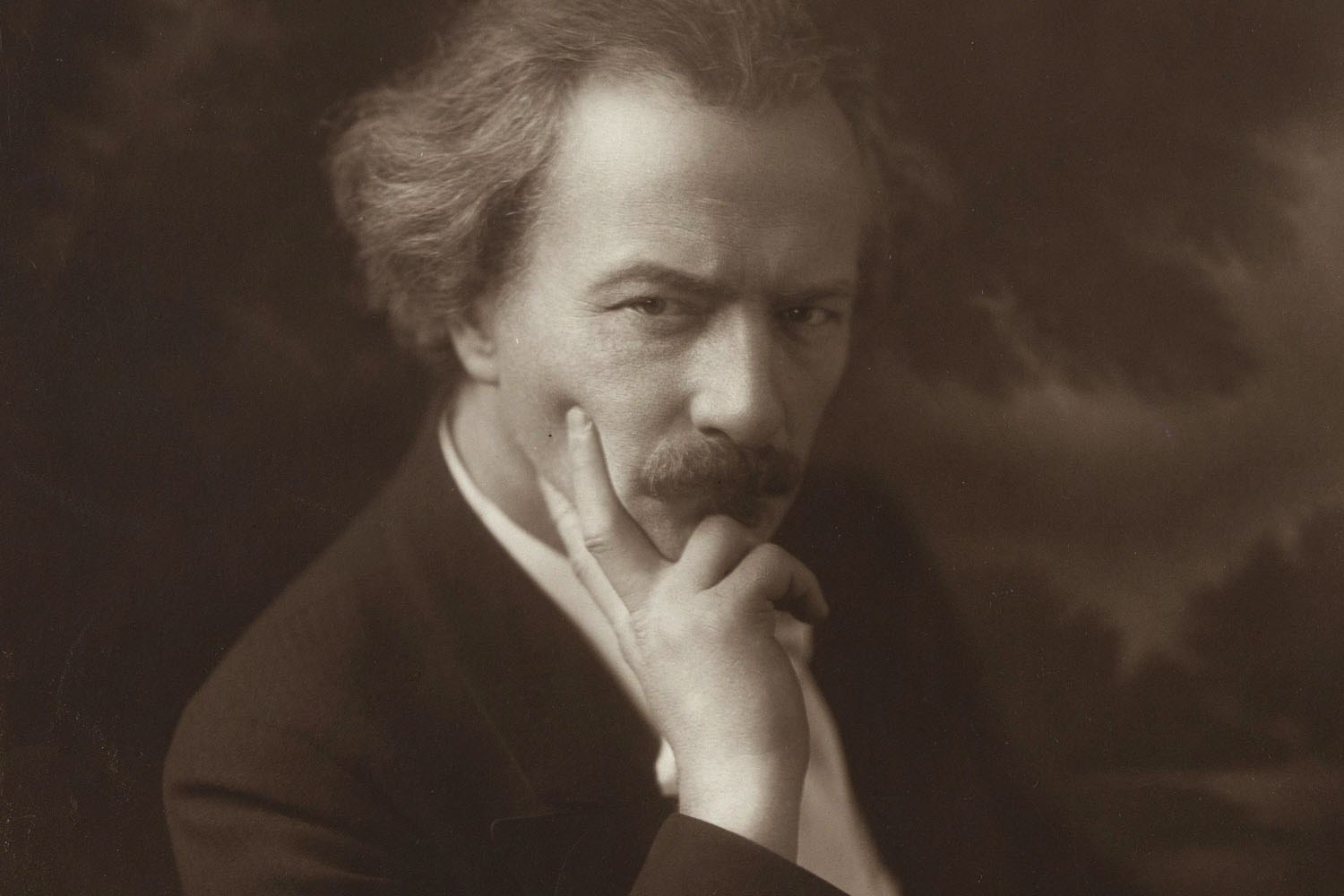

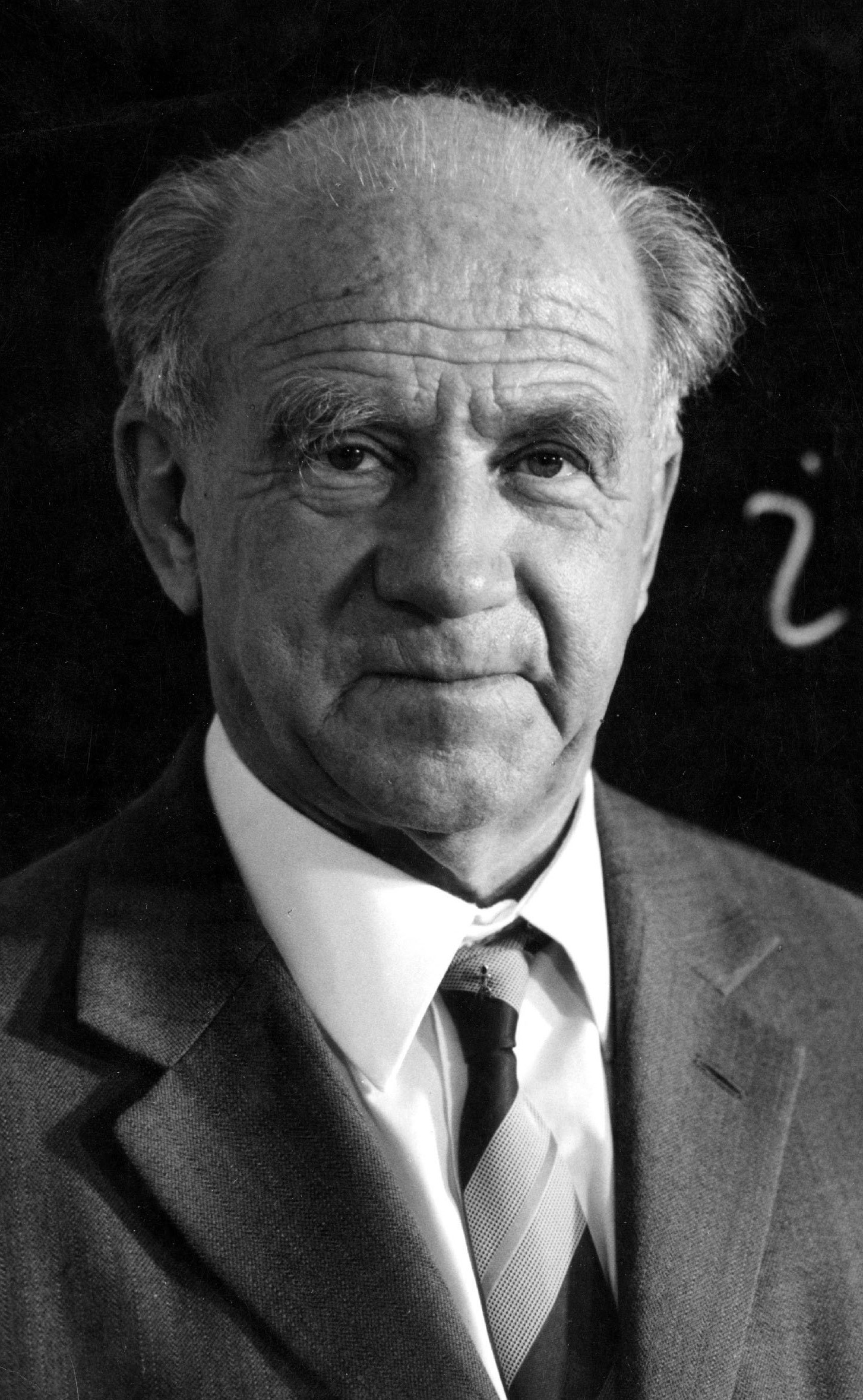

Many of my other revelations came in Poland, from hearing the inaugural International Chopin Competition on Period Instruments in Warsaw, to finally visiting Katowice’s recently built new concert hall, a stunning addition to Europe’s musical landscape. As Poland celebrates the centenary of regaining statehood, it has been revelatory to hear so much of Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the virtuoso pianist–composer who was a signatory to the Treaty of Versailles and an early prime minister of the country. And to see him: Warsaw’s National Museum put on a magnificent show about a figure who will no longer be quite so undervalued.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski, 1920 (photo: Wikipedia Commons)

Ignacy Jan Paderewski, 1920 (photo: Wikipedia Commons)

Leo Schofield

The STC’s adaptation of Ruth Park’s The Harp in the South trilogy was one of the ensemble’s most ambitious projects to date and a showcase for some of the country’s finest acting talent, a kind of Cloudstreet redux. At the other end of the theatrical scale, the exuberant Calamity Jane, vaulting from the pocket handkerchief-sized stage of the hundred-seater Hayes Theatre Company to Belvoir St Theatre and beyond, was a blast, proving that there is much to be said for unchallenging entertainment and evenings of pure fun. Virginia Gay’s wildcat performance in the title role was one to treasure forever, alongside another great Aussie star Gloria Dawn in Annie Get Your Gun in a big top on Brookvale Oval.

An initiative of cellist James Beck, the fledgling Sydney Art Quartet performs in the Yellow House, an art gallery in Potts Point. Always original and fresh, their programming hit new heights in September when they gave a joyful recital with guest soloist Erin Helyard. Playing first on harpsichord and later on fortepiano. Helyard is not only a noted musicologist and conductor but also a performer with the rare talent of engaging fully with his audience and charming the socks off ’em.

Virginia Gay in Calamity Jane (photo by John McRae)

Virginia Gay in Calamity Jane (photo by John McRae)

Peter Craven

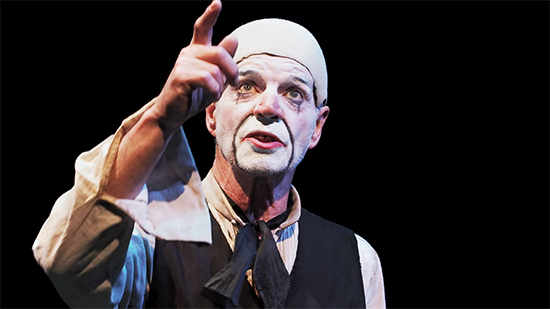

The best piece of theatre I saw this year and the greatest feat of acting was, by a long shot, Barry McGovern’s adaptation and one-man dramatisation of Samuel Beckett’s Watt (ABR Arts, 10/18). It had an absolutely unshowy precision through every wry desolation of a joke, a comical brilliance that was also poignant.

In music, what could touch the great Anne-Sophie Mutter, that transcendent violinist, doing the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto with Andrew Davis and the MSO (ABR Arts, 6/18). It was also marvellous to see Thomas Hampson, a baritone where musicianship and a sense of drama meet and fuse, performing Mahler’s Song of the Wayfarer: a princely performance in every sense.

And my film? Lady Bird, written and directed by Greta Gerwig, and featuring Saoirse Ronan. Such freshness and sap and that rare apparitional thing of recognising something you had never quite seen on a screen before.

Tali Lavi

In the ABC’s Mystery Road, the East Kimberley was revealed as a glorious embodiment of Country. Much of the power of this mesmerising television series, directed by Rachel Perkins, resides in what is repressed or unsaid. Aaron Pedersen’s masterful portrait of a flawed hero – enigmatic, wry, seething – and his nuanced interplay with Judy Davis make for unmissable viewing.

A revival of Thyestes (The Hayloft Project/Adelaide Festival) left me feeling cowed by its roar of violence and misogyny (ABR Arts, 3/18). Part of its disturbing nature was the sense of audience complicity as its humour plumbed the depths and laughter could still be heard.

Samuel Maoz’s masterpiece Foxtrot (ABR Arts, 6/18) was a sublime portrait of grief with elements of comic surrealism. Lior Ashkenazi and Sarah Adler were luminous as grieving parents. The question it poses – how does one live in the face of so much pain? – was encountered with a pulsating humanity.

A still from Foxtrot (Sharmill Films)

A still from Foxtrot (Sharmill Films)

Paul Kildea

Five works dating from 1996 to 2014 and performed in a Portrait Concert at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music put the unrestrained imagination of Liza Lim on stage. My favourite – The Alchemical Wedding – brings together different musical and philosophical traditions amid much whirring and clanking and sheer virtuosity.

I could not attend the performance, but the final rehearsal of Siobhan Stagg singing Strauss with the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra (at the Melbourne Recital Centre) under Johannes Fritz was exquisite. The orchestral playing was superb, Fritz an inspiring leader, Stagg simply radiant. A similar radiance is to be experienced at The Brunswick Green in Melbourne where each Thursday night Michelle Nicolle performs with her band. She really is an astonishing artist, fielding jazz requests with grace and an impossibly good memory. And what a voice!

David Greco and Erin Helyard launched their brilliant new recording of Schubert’s Winterreise with an inspiring presentation in which they discussed their many startling departures from the received traditions associated with this cycle.

Promotion image of Siobhan Stagg

Promotion image of Siobhan Stagg

Patrick McCaughey

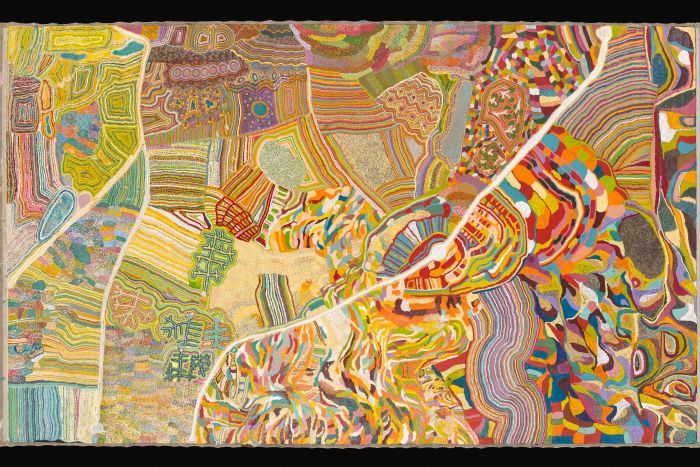

Three exhibitions changed the landscape in their respective fields. The National Museum’s Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters was the most exhilarating and instructive exhibition of Aboriginal art I have ever seen. The exhibition conveyed in nuce the journey across the landscape and the cosmogony that shaped it. The Metropolitan’s bold experiment to show and talk about modern art differently in Met Breuer (the old Whitney building) has given us profound exhibitions, none more than Like Life: Sculpture, Colour and the Body, 1300–Now. The excitement comes from the shock of juxtaposing ancient and modern. Jeff Koons’s sad Buster Keaton on a pony next to a fifteenth-century German polychrome carving of Christ on a Donkey was beyond riveting: it was piercing. Delacroix has taken over the Met this fall. Never have I seen him portrayed in such impassioned terms. André Breton’s ‘beauty must be convulsive’ could be the exhibition’s epigraph.

Hunting Ground, by Martumili Art Studio, part of the Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters exhibition (photo via National Museum of Australia)

Hunting Ground, by Martumili Art Studio, part of the Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters exhibition (photo via National Museum of Australia)

Susan Lever

The year began with sell-out performances of the marvellous musical version of Muriel’s Wedding (ABR Arts, 11/17). The Hayes Theatre Company’s delightful revival of Katherine Thomson and Max Lambert’s Darlinghurst Nights in January reminds us that there are other good Australian musicals in the repertoire, if we could only keep them in production. For Opera Australia, Barrie Kosky’s production of The Nose pushed Shostakovich’s absurd and wayward material to its hilarious theatrical limits.

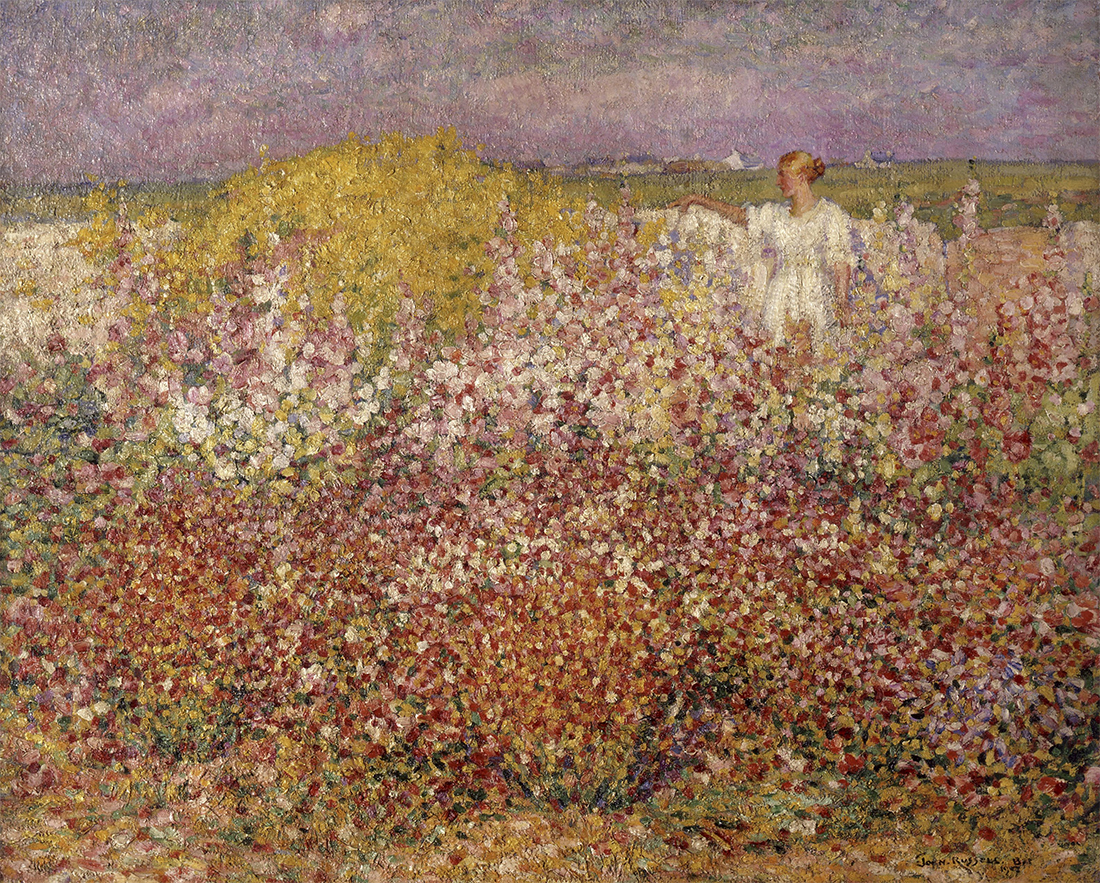

Later in the year, two art exhibitions were thoughtfully curated and full of beautiful work. The retrospective of John Mawurndjul’s work at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (I Am the Old and the New) was a revelation, full of masterpieces from this modest and prolific artist. At the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the John Russell retrospective displayed his rarely seen work with companion pieces from his more famous friends (ABR Arts, 7/18). A complementary pleasure was a trip across the harbour to see Luke Sciberras and Ewan Macleod’s paintings of Belle Isle, organised as a tribute to Russell by the Manly Art Gallery.

Mrs Russell among the flowers in the garden of Goulphar Belle Île 1907, by John Russell. Musée dOrsay Paris, held by the Musée de Morlaix bequest of Mme Jouve, 1948

Mrs Russell among the flowers in the garden of Goulphar Belle Île 1907, by John Russell. Musée dOrsay Paris, held by the Musée de Morlaix bequest of Mme Jouve, 1948

Peter Tregear

One standout for me was Melbourne Opera’s Tristan und Isolde (ABR Arts, 2/18). A supreme creative achievement of Western culture, Wagner’s opera is exceedingly difficult to perform. The fact that a local company was able to do so without drawing on any public subsidy belies those who might otherwise wish to claim that this art form neither comes from, nor addresses, modern Australia.

Ladies in Black – Bruce Beresford’s cinematic adaptation of Madeleine St John’s novel – evokes a late-1950s Australia where a profound lack of aesthetic experiences and imagination was the expected norm. Nominally a film about women and dresses, it is in fact as much about men and music and food and drink and sex, and the liberating impact made by a group of Hungarian wartime immigrants who knew about them all.

Julia Ormond as Magda Szombatheli in Ladies in Black

Julia Ormond as Magda Szombatheli in Ladies in Black

Ben Brooker

It’s often the shows I don’t have to write about that I enjoy the most – coincidence perhaps, or the result of being ‘off duty’. There were two such productions for me this year: MTC’s searing The House of Bernarda Alba, adapted by Patricia Cornelius from Federico García Lorca’s classic tragedy; and Chamber Made Opera’s unsettling theatrical exorcism Dybbuks at Theatre Works. With exceptional casts and creative teams dominated by women, both were spooky, fiercely political evocations of patriarchy and its spectres. Also of note were two musical experiences: Melbourne Film Festival’s stunning 4K presentation of Prince’s 1987 concert film Sign o’ the Times – a reminder of the Purple One’s much-missed genius – and famed choral ensemble Rundfunkchor Berlin’s immersive and deeply affecting Human Requiem, a ‘broadening’ of Brahms’s German Requiem that proved revelatory in its democratising intermingling of choristers and audience.

The cast of Chamber Made Opera's Dybbuks at Theatre Works (photo by Pia Johnson)

The cast of Chamber Made Opera's Dybbuks at Theatre Works (photo by Pia Johnson)

Tim Byrne

This year saw a resurgent Victorian Opera stage two superb productions – one a concert performance of Bellini’s The Capulets and the Montagues, with a predictably virtuosic Jessica Pratt and a stunning Caitlin Hulcup, and the other a fully realised triumph in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell. These works’ rarity only increased their appeal.

Two towering solo performances stuck in the memory: Colin Friels at his most exposed and generous in Scaramouche Jones (ABR Arts, 8/18) and Barry McGovern in complete control of the Beckett world view in Watt.

The finest, most surprising work of the year was Stephanie Lake’s Colossus for the Melbourne Fringe. With a cast of fifty dancers on the tiny Fairfax stage, this surging, multifarious piece managed to be both expansively political and almost microscopically intimate. With this sumptuous and thorny masterpiece, Lake has cemented herself at the heart of Australian dance.

Colin Friels in Scaramouche Jones at Arts Centre Melbourne (photo by Lachlan Bryan)

Colin Friels in Scaramouche Jones at Arts Centre Melbourne (photo by Lachlan Bryan)

Fiona Gruber

The Sydney White Rabbit Gallery mounts impeccably produced shows of contemporary Chinese artists. I relished The Sleeper Awakes in March. Taking its title from the H.G. Wells novel, this group show imagines waking in China forty years after the death of Mao Zedong to find his vision strangely distorted. It was deliciously witty, subversive, and lyrical, with immaculately realised works. In May, I visited Manifesta, Europe’s roving biennale; this year it is in Palermo, with work centred on the three hot topics of our times: migration, the environment, and digital surveillance. Sicily has been at the crossroads of Africa and Europe for millennia. With Manifesta, life, history, and urgent contemporary art combined brilliantly.

Finally, at this year’s Melbourne Festival, it was a treat to see the Belarus Free Theatre work with local actors to create a searing show about cultural identity. Trustees was exhilaratingly daring. Bravo!

Daniel Schlusser and Tammy Anderson in Trustees by Belarus Free Theatre (photo by Nicolai Khalezin)

Daniel Schlusser and Tammy Anderson in Trustees by Belarus Free Theatre (photo by Nicolai Khalezin)

Barney Zwartz

Shostakovich provided my finest musical moments of 2018. Opera Australia gave us his satirical opera, The Nose. Wildly inventive and anarchic, it has been described as an operatic Monty Python; Barrie Kosky’s production, conducted by Andrea Molino, realised this ingeniously. In September, I was lucky to be in Chicago for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s opening concert of the 2018–19 season: Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony, Babi Yar. Built around five Yevgeny Yevtushenko poems with basso profundo (Alexey Tikhomirov) and male chorus, it is one of the great masterpieces of political protest. Riccardo Muti drew an anguished, tender performance.

Close behind was Victorian Opera’s sublime account of Debussy’s haunting Pelléas et Mélisande, the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s concert performance of Act One of Wagner’s Die Walküre (ABR Arts, 8/18), while Melbourne Opera punched wildly above its weight with a fine Tristan und Isolde. Honourable mentions: OA’s Don Quichotte, starring Ferrucio Furlanetto (ABR Arts, 3/18) and the MSO’s The Dream of Gerontius, with Stuart Skelton (ABR Arts, 3/18)

Warwick Fyfe as Sancho Panza and the chorus in Opera Australia's production of Don Quichotte (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Warwick Fyfe as Sancho Panza and the chorus in Opera Australia's production of Don Quichotte (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Peter Rose

In a year of debased politics around the world, galleries and theatre of all kinds remained a refuge for illumination, brio, and liberal values. Three operas stood out: the Met’s revival of Mary Zimmerman’s stylish production of Lucia di Lammermoor (ABR Arts, 5/18), with Pretty Yende and Michael Fabiano as Donizetti’s demented lovers; WASO’s concert version of Tristan und Isolde, with the phenomenal Stuart Skelton and a sensational stand-in, Gun-Brit Barkmin; and the Australian première of Brett Dean’s Hamlet, even better than the 2017 Glyndebourne performance. Paul Lewis, that most probing and elegant of pianists, continued his revelatory series of Haydn and Brahms recitals. Anne-Sophie Mutter, in her Melbourne début, gave one of the great performances of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto.

Theatrically, Barry McGovern was hilarious and tragic and suave in his adaptation of Beckett’s Watt. But the performance that stirred me most was the revival of Edward Albee’s Three Tall Women (ABR Arts, 4/18), with the incomparable Glenda Jackson.

Glenda Jackson in Three Tall Women

Glenda Jackson in Three Tall Women

Ron Radford

It was pleasing to see no fewer than four Australian colonial exhibitions in 2018, given that there have only been fifteen such shows in the thirty years since the Bicentenary. The Art Gallery of Ballarat showed the brilliant Eugene von Guérard as a great travelling artist and displayed, for the first time, his lively on-the-spot drawings with his oils. Next, an exhibition of convict portraitist Thomas Bock opened in his birthplace, Birmingham, then Hobart. It excluded his oils, concentrating on his uniquely individual Aboriginal portraits. The third show, opening at the National Gallery of Australia, displayed Aboriginal images by Bock and other artists. It centred on Benjamin Duterrau’s The Conciliation, which he called ‘the national picture’. The fourth and most ambitious was the National Gallery of Victoria’s huge survey Colony: Australia 1770–1861 (ABR Arts, 4/18). Incomprehensively displayed, it was a noble but cluttered failure compared with the more focused shows. It is to be hoped these exhibitions herald a trend in honouring our visual arts heritage.

John Glover, The River Nile, Van Diemen's Land, from Mr Glover's farm, 1837 (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1956)

John Glover, The River Nile, Van Diemen's Land, from Mr Glover's farm, 1837 (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1956)

Will Yeoman

It was a rich year for West Australian art lovers. There were the chthonic, textured evocations of the Pilbara and Kimberley landscapes encapsulated by trios of quasi-anthropomorphic vessels in Fragment, Stewart Scambler’s superb exhibition at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery; but also the Renaissance and Baroque splendours of Caravaggio, Guercino, Pontormo et al. in A Window on Italy – The Corsini Collection: Masterpieces from Florence at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (ABR Arts, 2/18).

Musically, the highlight was undoubtedly WASO’s concert performance of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, conducted by Asher Fisch and featuring the incomparable Stuart Skelton. I also enjoyed Black Swan State Theatre Company’s productions of Ray Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (ABR Arts, 5/18) and Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins (ABR Arts, 6/18), while Perth Festival’s presentations of Evgeny Grishkovets’s Farewell to Paper and Yeung Fai’s Hand Stories offered contrasting yet similarly elegiac views on culture, history, tradition, and innovation. Joe Stephenson’s wonderful documentary on Ian McKellen, Playing the Part, was the icing on the cake.

Kelton Pell, Amy Mathews, and Jacob Allan in Black Swan State Theatre Companys Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (photo by Philip Gostelow)

Kelton Pell, Amy Mathews, and Jacob Allan in Black Swan State Theatre Companys Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (photo by Philip Gostelow)

Gillian Wills

In April, the twenty-five-year-old Alexander Prior conducted the Queensland Symphony Orchestra as if it were a massive piano, in a brilliant concert of music by Brahms, Debussy, and Ginastera. Prior’s gift for shaping the micro was balanced by an unusually luxurious overarching coherence. Also in April, as part of the Wave Festival, Gordon Hamilton’s arrangements of Horrorshow hits from albums Bardo State and The Grey Place celebrated the versatility of Queensland Symphony Orchestra instrumentalists and the Hip-Hop collective. In this blend of Hip Hop and Classical, bassist Paul O’Brien mapped out jazzy grooves as skilfully as he underpins QSO’s classical works. Esther Hannaford was riveting as Carole King in Beautiful, presented by QPAC in July. Polished, authentic, funny, with stylised dance routines recalling The Shirelles. Beautiful, delighted the audience. King and Gerry Goffin’s chart-toppers were belted with infectious authority. Southern Cross Soloists’ stunning August concert, Star of the Concertgebouw, featured Principal Trumpeter Miroslav Petkov.

Miroslav Petkov, Principal Trumpeter of The Royal Concertgebouw Amsterdam

Miroslav Petkov, Principal Trumpeter of The Royal Concertgebouw Amsterdam

Ian Dickson

Opera Australia has often been accused of playing safe and rehashing the same repertoire, but with its co-production of Dmitri Shostakovitch’s The Nose it not only struck out, it struck gold. Barrie Kosky’s wildly inventive, hilarious production was matched by Andrea Molino’s incisive conducting and a superb cast led by Martin Winkler.

The STC is developing a rapport with the ambitious and challenging British playwright Lucy Kirkwood. Sarah Goodes’s production of Kirkwood’s post-apocalyptic play The Children (ABR Arts, 4/18) cleverly balanced the humour and horror of the piece, ably abetted by her magnificent trio of actors, Pamela Rabe, William Zappa, and Sarah Peirse. Can we hope for Kirkwood’s latest play, Mosquitoes, in the future?

Small in scale and light in touch it may be, but Bruce Beresford’s Ladies in Black is an absolute delight. The cast is perfect: unfair though it is to single out anyone, the gorgeous Angourie Rice as the protagonist, Leslie, who blossoms into Lisa, must be mentioned.

William Zappa and Pamela Rabe in The Children (photograph by Jeff Busby)

William Zappa and Pamela Rabe in The Children (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Kim Williams

The highlights of the past year have been two Adelaide Festival productions: Neil Armfield’s gripping production of Brett Dean’s magical opera Hamlet (ABR Arts, 3/18), with a stunning performance by Allan Clayton as the Prince. Also at the Festival was Belgian genius Ivo van Hove’s breathtaking Kings of War, his Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s melding of Shakespeare’s Henry V, Henry VI, and Richard III into a play that went to the heart of leadership and the polarities and venalities attaching to it. This memorable, singular piece of theatre integrated video and live action perfectly with impeccable theatrical purpose. Another wondrous night was at the National Theatre in London with another Ivo van Hove piece – his recreation of Paddy Chayefsky’s Network, with Bryan Cranston in the central role as Howard (‘I’m mad as hell’) Beale. In a year of theatrical marvels, Kate Mulvany’s adaptation of Ruth Park’s The Harp in the South trilogy was a theatrical highlight that touched the heart and mind indelibly.

Mary Finsterer’s The Lost: Missed Tales No. 3, for the MSO (self-confession: I commissioned it), the Canadian baroque ensemble Tafelmusik, and Ross Edwards’s various seventy-fifth anniversary performances rounded out the year with some wonderful music.

Allan Clayton in Hamlet at the 2018 Adelaide Festival photograph (photo by Tony Lewis)

Allan Clayton in Hamlet at the 2018 Adelaide Festival photograph (photo by Tony Lewis)

Lee Christofis

Three timely and absorbing dance dramas exploring invasion, colonisation, and the dragooning of Indigenous peoples into indentured labour or wars were this year’s dance highlights. Starry nights at Perth’s Quarry were perfect for Milky Way: Ballet at the Quarry (ABR Arts, 2/18), a meditation on the apotheosis of restless souls. Gary Lang. Deborah Cheetham, a Yorta Yorta woman, superbly enhanced Milky Way’s mystery, singing Henryk Gørecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs to a WASO recording. Xenos, a haunting critique of the British Raj and the conscription of native men into wars they could never comprehend, was exquisitely crafted by Bangladeshi-British choreographer Akram Khan to mark his retirement from the stage (ABR Arts, 3/18). More contemporary, and pressing, was Marrugeku Dance Theatre’s Le Dernier Appel (The Last Cry), a multiracial, cross-art-form psychodrama, which explored New Caledonia’s Kanak people’s current yearning for liberation from around 180 years of French colonialism (ABR Arts, 8/18).

Performers of Marrugeku Dance Theatre's Le Dernier Appel (photo by Prudence Upton)

Performers of Marrugeku Dance Theatre's Le Dernier Appel (photo by Prudence Upton)

Brian McFarlane

Perhaps the film that lingers most painfully in the memory is the Russian drama Loveless (ABR Arts, 4/18). Few films maintain such a steely grip on the viewer’s involvement as it traces the disappearance of a child of divorcing – and solipsistic – parents. Andrey Zvyagintsev’s rigorous direction of a tragic story at odds with the luminous beauty of the landscape asks a great deal of audiences, and offers a great deal in return. There is pain of a different kind to respond to in Dominic Cooke’s version of On Chesil Beach, scripted by its author, Ian McEwan, evoking a period of sexual inhibition, but convincingly arriving at a muted yet affecting outcome (ABR Arts, 10/17). Bruce Beresford’s Ladies in Black, a witty, humane version of Madeleine St John’s novel, captures the time and place and interweaves several personal stories with larger social changes. The result is a kindly but never sentimental piece of recreation.

Michael Halliwell

Three very different operas were my highlights of the year. Firstly, a musically ravishing Parsifal as part of the Bavarian State Opera Festival (ABR Arts, 7/18). While the production was inconsistent, it was probably the most complete musical performance of this monumental work I have experienced, with the dream casting of Jonas Kaufmann as Parsifal and Nina Stemme as Kundry. Another standard repertoire opera, La Traviata, was a landmark event, not so much for the production or overall performance, but for the outstanding role début of rising Australian star Nicole Car in the challenging title role (ABR Arts, 3/18). Finally, a welcome revival of Brian Howard’s Metamorphosis (ABR Arts, 9/18) suggested that Opera Australia are looking at reviving neglected Australian operas in exciting venues – in this case in the Surry Hills Workshops of the company.

Simon Lobelson in Opera Australia's 2018 production of Metamorphosis at The Opera Centre Scenery Workshop

Simon Lobelson in Opera Australia's 2018 production of Metamorphosis at The Opera Centre Scenery Workshop

Sophie Knezic

The ascendancy of sound art as a medium of urgent exploration by contemporary artists was evident in several Melbourne exhibitions. Sensitively curated and politically astute was Joel Stern and James Parker’s Eavesdropping: a purview into the legislative complexities of listening and overhearing, whose highlights included works by artists associated with the London-based research agency Forensic Architecture. The potency of sound was also probed by David Chesworth and Sonia Leber in their mid-career survey show Architecture Makes Us, now interwoven with the nature of time and obsolescence. A suite of alluring works included Myriad Falls (2017), a slick pseudo-corporate video exposing the mechanisms of analogue wristwatch maintenance filmed inside a horologist’s workshop. Both exhibitions scrutinised the ways in which – mostly beneath our threshold of general awareness – sounds, especially private ones, can be extracted, co-opted, and surveilled.

Susan Schuppli, Listening to Answering Machines, 2018, from Eavesdropping at the Ian Potter Museum of Art (photo by Christian Capurro)

Susan Schuppli, Listening to Answering Machines, 2018, from Eavesdropping at the Ian Potter Museum of Art (photo by Christian Capurro)

Michael Morley

Nothing has left as haunting an impact as Jochen Sandig and Sascha Waltz’s reimagining, with Rundfunkchor Berlin, of Brahms’s German Requiem as Human Requiem. At the other end of the musical and theatrical scale was the Hayes Theatre’s exhilarating, knockabout production of Calamity Jane, as if Peter Brook’s ideas on ‘rough theatre’ had been applied to the Hollywood musical.

Acting performances of the year were all on television. With Benedict Cumberbatch as the eponymous anti-hero, the final episode of Patrick Melrose spoke of ‘contempt, pity, rage, terror, tenderness’. Cumberbatch’s performance had all these and more. In A Very English Scandal (BBC First) we had Hugh Grant’s brilliant turn as the UK politician Jeremy Thorpe, matched by Ben Whishaw as his erstwhile lover and nemesis, Norman Scott. This series was television at its best. Perhaps the ABC could divert funds from Gulfstream or Jetboat for a repeat screening?

Hugh Grant as Jeremy Thorpe and Ben Whishaw as Norman Scott in A Very English Scandal (photo by BBC/Blueprint Television)

Hugh Grant as Jeremy Thorpe and Ben Whishaw as Norman Scott in A Very English Scandal (photo by BBC/Blueprint Television)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.