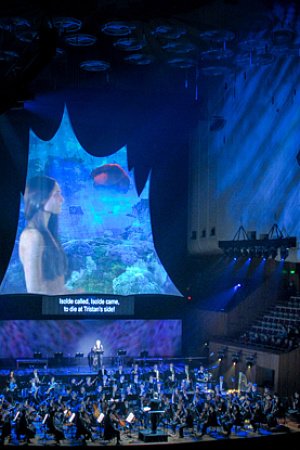

Pelléas et Mélisande (Sydney Symphony Orchestra) ★★★★

As one of the jewels in this year’s program by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Claude Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, rarely performed in Australia, has finally returned to the Sydney Opera House. This is not the first time that the SSO has ventured into opera. Judiciously, though, it never competes directly with the national company, selecting repertoire neglected by OA. In 2014, it performed Elektra by Richard Strauss, to critical acclaim, followed by Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde a year later. Later this season, Béla Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle will be on the programme.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comment (1)

Managed to hear part of the radio broadcast and it did not have the same effect as seeing it live. Less than most, oddly.

Thank you

Minnie

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.