James Ley

Harold Bloom was one of the last of the so-called ‘Yale critics’, who shaped the terrain of literary criticism in the latter half of the twentieth century. Bloom died in October 2019, and his final book, Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles, arrives two years after his death and caps a long and controversial career. In this issue, James Ley surveys this swansong by a critic who ‘came to style himself less as a theorist and more as a theologian of literature: the high priest and only admitted member of his own private religion’.

... (read more)Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles: The power of the reader’s mind over a universe of death by Harold Bloom

A curse on art, a curse on society: Government contempt for the ABC, the arts, and the academy

It is curious the way certain books can insinuate themselves into your consciousness. I am not necessarily talking about favourite books, or formative ones that evoke a particular time and place, but those stray books that seem to have been acquired almost inadvertently (all bibliophiles possess such volumes, I’m sure), and taken up without any particular expectations, books that have something intriguing about them that keeps drawing you back.

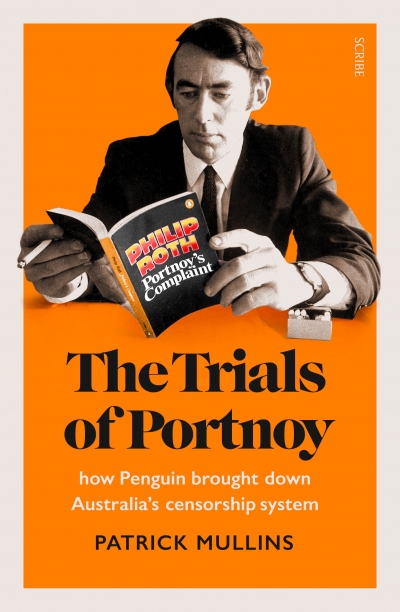

... (read more)In today's episode, we present James Ley’s hilarious and deeply serious review of The Trials of Portnoy by Patrick Mullins. James channels the memorable prose of Philip Roth himself. Mullins’s book chronicles the legal spat that surrounded Penguin's attempt to publish Portnoy's Complaint, Roth's controversial novel that was considered lewd and offensive by Australia's censuring authorities.

... (read more)The Trials of Portnoy: How Penguin brought down Australia’s censorship system by Patrick Mullins

Andrew McGahan’s first novel, Praise (1992), concludes with its narrator, Gordon Buchanan, deciding – perhaps accepting is a better word – that he will live a life of contemplation. This final revelation is significantly ambivalent. The unresponsive persona Gordon has assumed throughout the novel is something of an affectation. On one level, he is playing the stereotypical role of the inarticulate Australian male, but his blank façade is also defensive; it is a cover for his sensitivity. For Gordon, life is less overwhelming in a practical sense than in an emotional sense. His true feelings are a garden concreted over for ease of maintenance. He feels that the defining quality of human relationships is doubt, and this doubt confounds expression. ‘I’m never certain of anything I feel about a person,’ he says, ‘and talking about it simplifies it all so brutally. It’s easier to keep quiet. To act what you feel. Actions are softer. They can be interpreted in lots of different ways, and emotions should be interpreted in lots of different ways.’

... (read more)