Biography

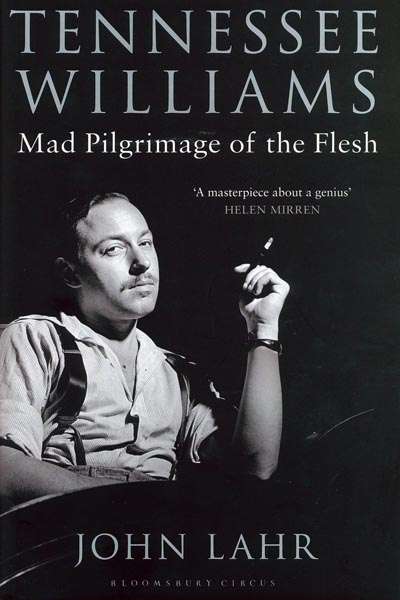

Tennessee Williams: Mad pilgrimage of the flesh by John Lahr

by Ian Dickson •

Margaret and Gough: The love story that shaped a nation by Susan Mitchell

by Carol Middleton •

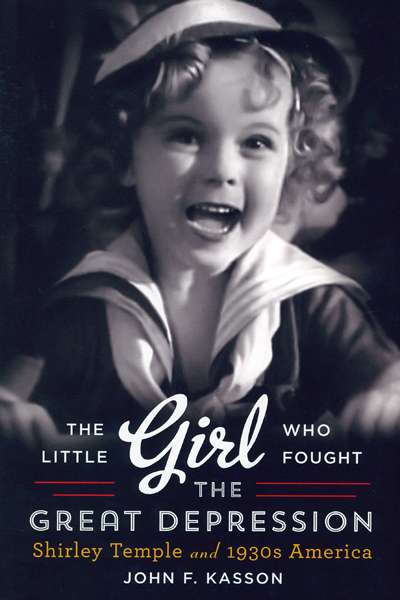

The Little Girl who Fought the Great Depression: Shirley Temple and 1930s America by John F. Kasson

by Desley Deacon •

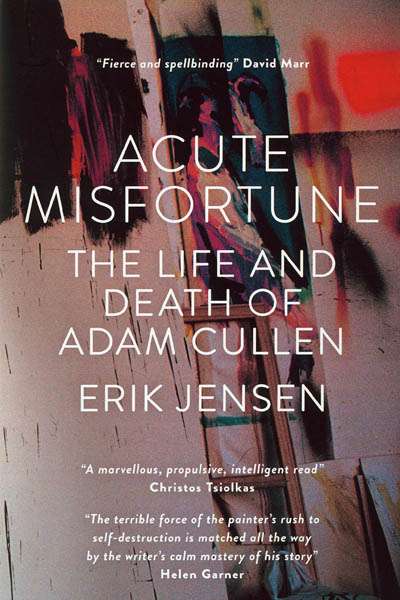

Acute Misfortune: The life and death of Adam Cullen by Erik Jensen

by Peter Rose •

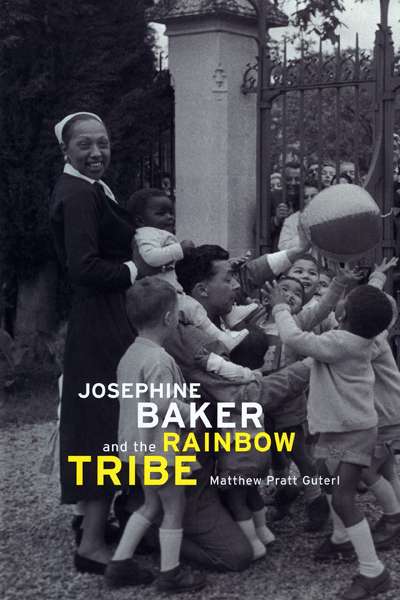

Josephine Baker and the Rainbow Tribe by Matthew Pratt Guterl

by Colin Nettelbeck •

An Unsentimental Bloke: The life and work of C.J. Dennis by Philip Butterss

by Dennis Haskell •

Worldly Philosopher by Jeremy Adelman & The Essential Hirschman edited by Jeremy Adelman

by Adrian Walsh •