Commentary

Biography seems relatively easy to produce, but difficult to write well. It is therefore treated with a certain amount of suspicion by academics. Historians tend to regard it as chatty, not primarily concerned with policy or the identification of social factors; literary people are more sympathetic, but, in order to blot out the prosy or the fact-laden, tend to revert to a default position. Biography for them is basically about writers, and best written by literary academics.

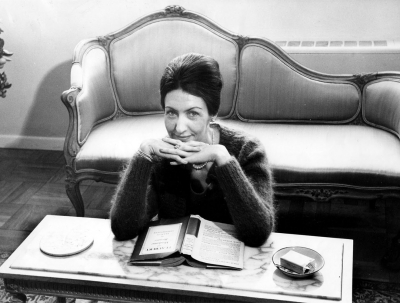

... (read more)In October 2009, Shirley Hazzard spoke at the New York launch of the Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature. Hazzard read from People in Glass Houses, her early collection of satirical stories about the UN bureaucracy. Her appearance serves to remind Australian readers that Hazzard continues to occupy a defining, if somewhat attenuated, place within the expansive field of what Nicholas Jose described in 2008, on taking up the annual Harvard Chair of Australian Studies, as ‘writing that engage[s] us with the international arena from the Australian perspective’. Jose went on to cite Hazzard’s most recent novel, The Great Fire (2003), as part of ‘a range of material which Americans would not necessarily think of as Australian’.

... (read more)I was in the house of a friend’s parents recently and noticed, stuck to the fridge door, a poem clipped from a newspaper, among the sundry magnets and notices. Companion to book reviews, its subtleties had taken their fancy as being more than ephemera. Good, I thought, these are poetry readers – an engineer and an art teacher – who can confidently duck and weave among poems that come their way and say, yes, this one’s a pleasure. But do they buy and read collections of poetry? Well, they would more often if …

... (read more)Antipodes: A North American Journal of Australian Literature was founded in 1987 as the journal of the American Association of Australian Literary Studies, itself founded the previous year. Both institutions are products of the Hawke era, when the still-simmering question of Australian identity and the Australian film boom of the early 1980s created an ideal state for Australians to be interested in (and to help fund) US literary culture’s own nascent interest in Australia.

From the beginning, it had no problem attracting prestigious contributors. A.D. Hope, Peter Carey, Les Murray, Thea Astley, Rosemary Dobson, and Mudrooroo were all featured in early issues. Even Patrick White consented to be profiled, though not formally interviewed, by our gentlemanly founding fiction editor, Ray Willbanks. Paul Kane, our poetry editor, has always made sure we are vitally engaged with the best and most exciting Australian verse. The journal continues to publish biannually, with most space devoted to refereed academic essays, but also including fiction, poetry, book reviews and the most recent addition – creative non-fiction, a hybrid genre in which regular contributors such as Ouyang Yu, Elizabeth Bernays, and the ‘Trans-Tasman’ figure Stephen Oliver have excelled.

... (read more)A New Literary History of America edited by Greil Marcus and Werner Sollors

Cynthia Ozick’s most recent collection of criticism, The Din in the Head (2006), contains a brief but engaging essay called ‘Highbrow Blues’. It begins with her musing about a gaffe made by Jonathan Franzen following the publication of The Corrections (2002). Oprah Winfrey had selected Franzen’s novel for her televised book club, which was popular enough to turn any work she chose into a bestseller, but Franzen was uncomfortable with her program’s folksiness. He felt that the club’s reputation for featuring works of middlebrow fiction did not fit with his literary ambitions and that an appearance on the Oprah Winfrey Show was not likely to enhance his credibility. ‘I feel,’ he explained, ‘like I’m solidly in the high-art literary tradition.’ Brickbats flew from all directions. But why, wonders Ozick, did Franzen’s remark seem so jejune?

... (read more)Holden Caulfield is a garrulous bore. Seymour Glass is a phoney. Franny and Zooey are spoiled brats. And J.D. Salinger is a media tart. All these things are partly true. To take the last first: there is surely a ring of truth about Imre Salusinzsky’s recent spoof obituary in which Jay Leno and David Letterman are quoted expressing their sadness at the loss of a favourite regular guest who was always ready to front up and sparkle as he promoted an endless succession of Catcher in the Rye merchandise. Salinger, who died on January 27, aged ninety-one, may not have done such things, but at least one of his alter egos might.

... (read more)In 2004, Somersault, a drama of youthful coming to terms with life’s challenges, scooped the pool at the Australian Film Institute’s annual awards. It was a melancholy comment on the state of the local industry that no other films could compete with this affecting but scarcely remarkable work. How different the situation will be in 2009.

... (read more)Clive James has been at the business of writing now for so long that his literary activities have almost outlived the fame that used to get in the way of their apprehension. Twenty or so years ago, it was possible to think that the man who clowned around in those ‘Postcards’ travelogues on television, and who seemed to reach some apogee of self-satisfaction and self-definition chatting to celebrities on the box, was just slumming it when it came to literature; that he had bigger fish to fry than this diminished thing, even, if he was forever reminding us of the grandness of the refusal he had made.

... (read more)In the anniversary week of Barack Obama’s election, the New York Yankees won the World Series, as all the world surely knows by now. The victory might have guaranteed a celebration, even in an America where unemployment hit ten per cent in the same week, but the glitz of the Yankees’ Friday ticker-tape parade through Lower Manhattan’s sombre but not sobered financial district was overshadowed by the news of the mass shooting at Fort Hood in Texas by American-born Major Nidal Malik Hasan.

... (read more)A year ago, I came to Australia prepared to spend the first half of my sabbatical leave completing a book on John Keats. Never having been to Australia, I was eager to spend some time here: five months in all. When I participated in the 2008 Mildura Writers Festival, it became clear to me that something both delightful and extraordinary was at work. There was a fine group of writers, including Les Murray, David Malouf, Alice Pung, Alex Miller, Sarah Day, and Anthony Lawrence. But what made the festival remarkable was the combination of conviviality and serious talk about literature and ideas that surpassed anything in my previous experience, which included far more such events than I could begin to count.

... (read more)