Commentary

Kenneth Cook was always a little surprised by the success of Wake in Fright. He dismissed it as a young man’s novel, as indeed it was; he published it in 1961, when he was thirty-two. Among his sixteen other works of fiction he was prouder of Tuna (1967), a partial reimagining of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea set off the coast of South Australia, and The Man Underground (1977), which dealt with opal mining. Perhaps he preferred them because he had enjoyed the research involved. It is true that both are better crafted, more assured, than the novel that made his name. But he could never quite accept that Wake in Fright delineated grim truths about the bush and its inhabitants that his other novels do not capture.

... (read more)Perhaps the most influential guide to ‘theory’ in Australia in the 1980s was Terry Eagleton’s Literary Theory: An Introduction (1983). The cover of my paperback edition features a detail from Jan Vermeer’s painting Mistress and Maid, in which a respectful domestic servant hands a document to her mistress, who is seated at a writing table. I take this to be a visual allusion to Alexander Pope’s formulation in An Essay on Criticism that ‘Criticism [is] the Muse’s Handmaid’. Eagleton’s polemical refusal of that secondary and facilitating role was influential in turning a generation of Australian literary critics from ‘criticism’ to ‘critique’. From Graeme Turner’s National Fictions (1986) and Kay Schaffer’s Women and the Bush (1987) to my own Writing the Colonial Adventure (1995) and Susan Sheridan’s Along the Faultlines (1995), the cultural-nationalist and new-critical canons alike were supplemented by alternative canons – feminist, realist, postcolonial and ‘popular’ – as texts were subjected to rigorous ideological critique for their representations of class, race, gender and nation. Criticism was no longer the handmaid to literature; a hermeneutics of scepticism and suspicion prevailed.

... (read more)The new English edition of a selection of Harwood’s poems comes with an excellent editorial pedigree. With his co-editorship of Gwen Harwood: Collected Poems 1943–1995 (2003) and his editorship of A Steady Storm of Correspondence: Selected Letters of Gwen Harwood 1943–1995 (2001), Gregory Kratzmann has established himself as the foremost of Harwood scholars. As a major critic of Australian poetry, Chris Wallace-Crabbe was an early champion of Harwood’s poetry, with a particular affinity, demonstrated in his own poetry, for the wit and wordplay that are distinguishing marks of Harwood’s work.

... (read more)There is a timeless quality about some Australian authors that causes one to applaud when discerning publishers revive their work for new generations of readers. Wakefield Press’s reissue of Alan Moorehead’s The Villa Diana, first published in 1951, presents this fecund author’s book of essays, now subtitled ‘Travels in Post-war Italy’ ($24.95 pb, 224 pp, 9781862548459). It provides a neat introduction to Moorehead’s famous camera-like eye and his beguiling prose, which, as one commentator put it, offers ‘a long conversation that you wish would never end’.

... (read more)The judges of the early Miles Franklin Awards clearly knew what they were about. Their inaugural award went to Patrick White’s Voss in 1957; the second to Randolph Stow’s To the Islands in 1958. At the time, White was in the early stages of a distinguished career that would bring him Australia’s only Nobel Prize for Literature, while the precocious Stow also promised great things. Hailed as a literary wunderkind, he had published two novels, A Haunted Land (1956) and The Bystander (1957), and his first collection of poetry, Act One (1957), by the time he was twenty-two. When Act One was awarded the 1957 Gold Medal of the Australian Literature Society and To the Islands won it the following year, plus the Melbourne Book Fair Award and the Miles Franklin, he seemed to be embarked upon a stellar career.

... (read more)The physiotherapist I saw for a pinched nerve in my back not long ago turned out to be an avid reader of fiction. She would work her way through the Booker shortlist each year. But she wouldn’t read Australian novels. As she pummelled my knotted flesh, I wondered if this was the right moment to admit that I was a person who wrote such things. She explained that, having moved to Australia from South Korea as a twelve-year-old, she had been made to write essays at school about a book called A Fortunate Life that she found as painful as I was finding her pressure on my spine.

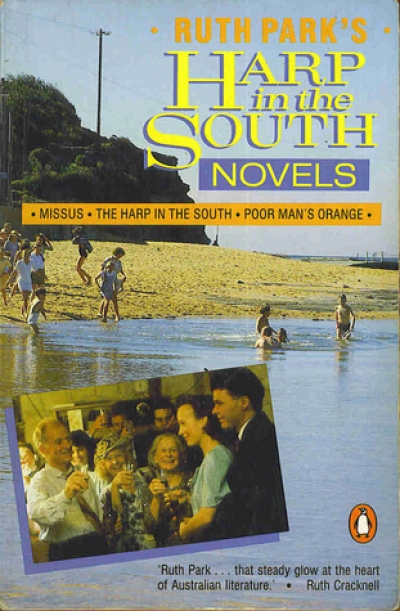

... (read more)The reissue in one volume of three of Ruth Park’s much-loved novels The Harp in the South (1948), its sequel Poor Man’s Orange (1949), and the prequel Missus (1985) is welcome. The trilogy completes the family saga, taking the Darcy family from its emigrant beginnings in the dusty little outback towns where Hughie and Margaret meet and marry, to their life in the urban jungle of Surry Hills, then for-ward to the 1950s when the next generation prepares to leave the slums for the imagined freedom of the bush. These are Australian classics, but classics of the vernacular, of the ordinary people. They should never be allowed to disappear from public consciousness.

... (read more)‘It wasn’t like that in the book’ is one of the commonest and most irritating responses to film versions of famous novels. Adaptation of literature to film seems to be a topic of enduring interest at every level, from foyer gossip to the most learned exegesis. Sometimes, it must be said, the former is the more entertaining, but this is no place for such frivolity.

... (read more)And now ’tis done: more durable than brass

My monument shall be, and raise its head

O’er royal pyramids: it shall not dread

Corroding rain or angry Boreas,

Nor the long lapse of immemorial time.

(Horace, Odes, III.xxx)

With what other words could one possibly begin a paper on philanthropy? Here we have the Roman poet Horace in full celebratory mode: his memorial will outlast even hard metal. What’s more, it comes at the end of the third book of Horace’s Odes, so many of which are dedicated to that legendary philanthropist Maecenas, who has given his very name to the arts of philanthropy, and who was the patron not just of Horace but also of Virgil and Propertius. Of course, then as now, Maecenas’s philanthropy was not altogether innocent, as even these poets suggest. Ultimately, the exquisite poetry of this Golden Age was in honour of the one and only emperor, Augustus, lauding his beneficence and the prosperity of his reign.

... (read more)When the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) opened in Canberra last December, more thoughtfulness was evident in its bookshop than the hang. The volumes are arranged by subject and in alphabetical order: the images accord to no principle beyond décor. Here are five writers; there, four scientists. The randomness of the whole embodies a culture of distraction. The root of this muddle is an evasion of whether the Gallery is to be guided by aesthetics or museology. The want of clarity is compounded by concern among staff not to be identified with a history museum.

... (read more)