Commentary

Robyn Archer debated Peter Singer during the 2015 Melbourne Writers Festival; their topic was 'Is Funding the Arts Doing Good?'. This is an edited version of her paper.

I hear that in New York

At the corner of 26th Street and Broadway

A man stands every evening during the winte ...

It was watching the empty buses leave in the dark outside the restaurant that did it. I was eating with my lover and my daughter on a June evening in Altona when I found myself being distracted by the rooms of light, quite empty, that floated behind my daughter's back. Every ten or fifteen minutes there would be another one heading off into the night, passengerless, ...

Many good books are published about Australian art, but few change the way we see and understand it. When Andrew Sayers’ Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century appeared in August 1994, it immediately did that, as the critic Bruce James was quick to recognise

Eminent psychologist Steven Pinker once described art as ‘cheesecake for the mind’. Many people think of culture as a luxury good, high up – and therefore low down – on Mazslow’s hierarchy of needs in comparison with basic physical requirements. Most of the time they are right. When they aren’t, the necessity for a detailed understanding of cultural proc ...

Once, when it was the beginning of the dry but no one could have known it yet, Dad drove us west – out past ‘Jesus Saves’ signs nailed to box trees, past unmarked massacre sites and slumping woolsheds, past meatworks and red-bricked citrus factories with smashed windows, and past one-servo towns with faded ads for soft drinks no one makes anymore – until we reached a cotton farm.

We stood on the old floodplain listening to the manager in his American cap, a battery of pumps and pipes behind him, boasting how much water these engines could lift once the river reached a certain height. To the left, an open channel cut through laser-levelled fields to the horizon.

... (read more)I am a ‘Sputnik’, born in the year the Soviet satellite launched the Cold War into space. The launching by the Russians of the first artificial Earth satellite on 4 October 1957 seemed to many in the West a threatening symbol of escalating superpower rivalry. And it did unleash extreme military anxiety and triggered what became known as the Space Race. Twelve years later, in the mid-winter of 1969, I remember waking up just before midnight to watch on television as a Saturn V US rocket, wreathed in smoke and flame, inched its way off the ground at Cape Canaveral. It powered mightily against the pull of gravity and triumphed. It was beginning its journey out of Earth’s atmosphere towards the Moon.

... (read more)As a freshwater ecologist, Alison Pouliot endeavours to understand the interplay of the processes that sculpt the Australian environment.

As an environmental photographer, she aspires to capture the intricacies and obscurities of these processes.

The insidious creeping nature of drought can sometimes lend itself more to images than words.

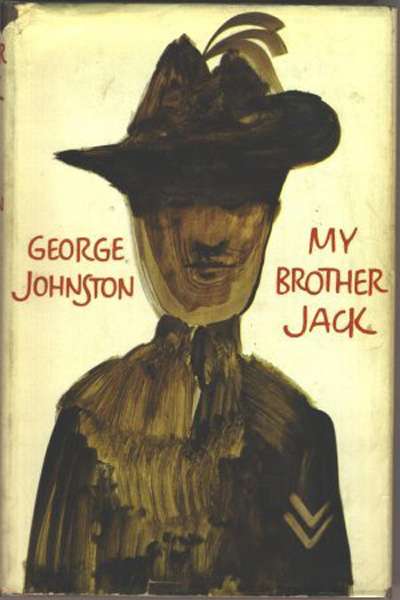

... (read more)The novel begins with the burnished quality of something handed down through generations, its opening lines like the first breath of a myth. Seductive in tone and concision, charged with an aura of enchantment, the early paragraphs of George Johnston’s My Brother Jack (1964) do more than merely lure the reader into the narrative. In these sentences, Johnston reveals the conviction and control of a master storyteller who, at the outset, establishes his ambition and literary lineage:

... (read more)Mary Cunnane, who has worked in the publishing industry since 1976, laments the laziness and irritation of those publishers who resent and underestimate unsolicited submissions from authors

... (read more)So here we are, talking about the so-called Cult of Wagner. No wonder some people recoil from the German composer, given such terminology. It’s not a new coinage of course, but it’s a fairly dubious one. One old acquaintance of mine, on hearing about this event, sent me an email demanding to know: ‘You are not besotted with it, are you??? Are you one of those ...