Literary Studies

In the dying days of the ignominious Conservative government that he led from 2019 to 2022, the former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson compared his fall to that of Shakespeare’s Othello. ‘It is the essence of all tragic literature,’ he claimed, ‘that the hero should be conspicuous, that he should swagger around and that some flaw should lead to a catastrophic reversal and collapse.’ Fintan O’Toole seizes on this self-serving, deluded commentary as an instance of a widespread misconception of Shakespeare’s tragic art and one that can be traced, in part, to the playing fields of Eton.

... (read more)Telling Lives: The Seymour Biography Lecture 2005-2023 edited by Chris Wallace

In her Preface to Telling Lives, editor Chris Wallace invites the reader to join a thought experiment: a group of biographer-refugees, driven by earthly global warming to reside on planet Alpha Centauri, ask themselves: ‘Did biographers play a role in the downfall of Homo sapiens on Earth?’ Were they, in other words, complicit in the culture of disinformation that contributed to global catastrophe? Writing in the ‘post-truth era’, Wallace highlights the centrality of truth in what has traditionally been termed the ‘biographical contract’.

... (read more)‘Australia has been a great experience,’ declares Seamus Heaney in a letter to Tom Paulin from Launceston, Tasmania, in October 1994. As well as visiting Melbourne, Brisbane, and Sydney, delivering poetry readings along the way, Heaney gave a lecture in Hobart on Oscar Wilde and The Ballad of Reading Gaol, ‘saying it was as much part of the protest literature of the Irish diaspora as “The Wild Colonial Boy” or the ballad of “Van Diemen’s Land”’. What he most enjoyed in Queensland was a drive through the country – ‘red earth and white-barked gum trees’ – to the town of Nambour, close to where his Uncle Charlie (his father’s twin brother) had lived in the 1920s. Heaney’s letters are a vivid interweaving of travelogue, literary allusion, poetic imagery, and personal history. Sharing pleasure in the power of words is fundamental, even when letter writing becomes a thing of duty, rather than beauty, and the unanswered mail piles up around him.

... (read more)Mothers of the Mind: The remarkable women who shaped Virginia Woolf, Agatha Christie and Sylvia Plath by Rachel Trethewey

Reading for this review I came across some apposite words by Jacqueline Rose, biographer of Sylvia Plath, cultural analyst and explorer of the lives and roles of women:

... (read more)Lands of Likeness: For a poetics of contemplation by Kevin Hart

There is a moment early on in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) – think of it as the novel’s opening gambit, the disturbance which sets its plot in motion – when the impish Clarisse McClellan attempts to rouse the book’s stolid and otherwise self-possessed protagonist, Guy Montag, from the partial oblivion in which he lives his life. She shadows him on his walk home from work one evening, verbally prodding him in the hope of puncturing what is evidently less a form of sincere conviction than it is a state of unthinkingness. After Montag rebuffs her questions one time too many, Clarisse finally complains, ‘You never stop to think what I’ve asked you.’

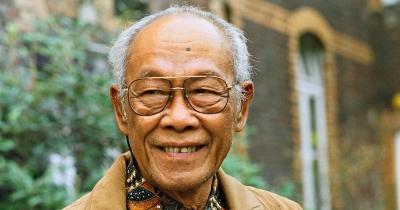

... (read more)What was the best decision Brian Johns ever made?

In 2005, Johns – legendary leader of Penguin Books Australia, publisher of Elizabeth Jolley, Thea Astley, Frank Moorhouse, and so many others, and later managing director of the ABC and SBS – nominated his publication of the Buru Quartet, by Indonesian author Pramoedya Ananta Toer. Johns was speaking at an event for Pramoedya’s Indonesian editor and publisher Joesoef Isak, who was receiving the inaugural PEN Keneally Award for publishing. This may have been a case of politeness on Johns’s part, but there are reasons to think this was likely a more considered assessment.

... (read more)The Bloomsbury Handbook to J.M. Coetzee edited by Andrew van der Vlies and Lucie Valerie Graham

In 2015, the Nobel Prize-winning author J.M. Coetzee released a volume of reflections on ‘truth, fiction and psychotherapy’ under the title The Good Story. The volume, co-written with Arabella Kurtz, a psychotherapist, preserves the distinctiveness of the viewpoints of the two interlocutors throughout. As we read these exchanges between the writer and the psychotherapist, we are in the realm not of ‘autrebiography’, where the self is endlessly reflected as if in a hall of mirrors, but of autobiography, where the self is transparent to itself and its own viewpoint. What we hear on Coetzee’s side is the plain voice of the author – an author not undone by an army of caveats about truth in the vein of the postmodern, an author who has not departed and been replaced by her readers. This is a voice that engages with Plato’s injunction against the poets in The Republic, a voice that finds value in the artifice of the ‘good story’ even as it acknowledges the failure to tell the story of the good, a voice that ruminates on whether truth as an ethical enterprise might even have disappeared from the psychotherapist’s consulting rooms. In the only mention of this work in the capacious Bloomsbury Handbook to J.M. Coetzee – it occurs in Nick Mulgrew’s chapter ‘Later Criticism and Correspondence’ – this statement is recorded:

... (read more)The Visionaries: Arendt, Beauvoir, Rand, Weil and the salvation of philosophy by Wolfram Eilenberger, translated by Shaun Whiteside

Wolfram Eilenberger’s previous book, the bestselling Time of the Magicians (2020), explored the four Germans – Ernst Cassirer, Walter Benjamin, Martin Heidegger, and Ludwig Wittgenstein – who ‘invented modern thought’. The Visionaries keeps to the formula, this time with women in the lead roles. It is described as a group biography, but Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Ayn Rand, and Simone Weil were very much not a group. Nor is it a biography: there is scant biographical information and no analysis of why they lived as they did. Apart from being born at the same time, writing books, and sharing what Eilenberger calls an ‘honest bafflement that other people live as they do’, the quartet have nothing in common: Arendt was a German Jew escaping the Gestapo; Beauvoir a French intellectual on a mission to enjoy herself; Rand a Russian émigré refashioned as an American neoliberal; and Weil a latter-day Joan of Arc. The closest any of them came to meeting was when Beauvoir, for whom the existence of others was ‘a danger to me’, was introduced to Weil, who had wept at the news of famine in China. It did not go well. The only thing that mattered, Weil announced, was a revolution to feed the world’s starving, to which Beauvoir ‘retorted that the problem was not to make men happy but to find the reason for their existence. She looked me up and down. “It’s easy to see you’ve never been hungry”, she snapped. Our relations ended right there.’

... (read more)The death of Gabrielle Carey earlier this year was a cruel loss for the Australian literary world, especially its Joyce community. I first met Gabrielle shortly after moving to Sydney from London in 2010. She invited me to her annual Bloomsday celebration, which took place in a Glebe pub. I was new in town and delighted to join the readings and revelry. I suspected, rightly, that my Dublin accent would glean me some credibility, if nothing else did.

... (read more)Retroland: A reader’s guide to the dazzling diversity of modern fiction by Peter Kemp

In the dying months of the last century, I took a crash course in Modern British Fiction. I had opted for the most contemporary course on the Oxford English MPhil that covered the most contemporary period (1880 to the present, then generally understood to have ended circa 1970). My elective choices had all been a little unpopular: rather than a term parsing Ulysses, I read all of Conrad; where the crowd chose Pound or Eliot for the poetry elective, I turned up at St John’s each week to talk about Yeats.

... (read more)