Literary Studies

Consuming Joyce by John McCourt & One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses edited by Colm Tóibín

James Joyce’s Ulysses was published 100 years ago by American Sylvia Beach, who ran a Parisian bookstore called Shakespeare and Company. The early history of the work was marked by controversy and censorship. The centenary is being marked by numerous publications in celebration of the work by writers, academic Joyceans, and even the odd Irish ambassador. John McCourt’s Consuming Joyce: 100 years of Ulysses in Ireland traces the reception of Ulysses in Ireland. As much a book about Ireland as it is about Ulysses, it follows the critical, institutional, and popular reception/consumption of the work through the different phases of Irish history.

... (read more)The Life of Such Is Life: A cultural history of an Australian classic by Roger Osborne

‘Such is life’ is a common phrase in Australian popular culture – it has even been tattooed on bodies – but Joseph Furphy’s novel of the same name, published in 1903, is often forgotten. Ned Kelly mythology suggests that he uttered this phrase just before being hanged in 1880, though some historians argue that what he actually said was, ‘Ah well, I suppose’. Long before Furphy (1843–1912) wrote his magnum opus, the stoic phrase was perhaps wrongly associated with a cult hero’s execution.

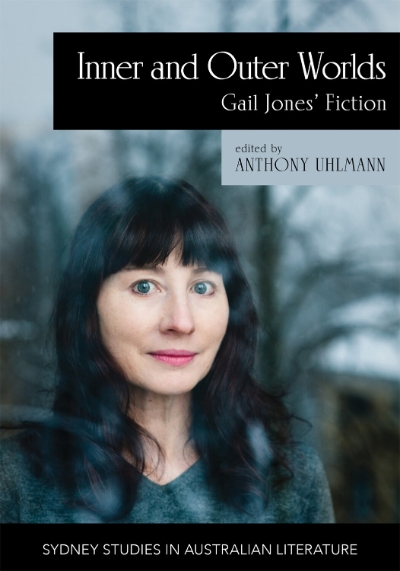

... (read more)Inner and Outer Worlds: Gail Jones’ fiction by Anthony Uhlmann

The novels of Gail Jones present a challenge to would-be critics. Jones being a formidable scholar in her own right, her eight novels to date pose sophisticated philosophical questions within their elegantly structured narratives. Her novels canvass aspects of human experience that are murky and complex: these are often forms of familial or romantic relationship shaped by loss, both personal and historical. The challenge for critics is that the novels are themselves thinking about the potential of fiction to do this kind of philosophical or ethical work. In this sense, Jones might seem to be one step ahead of the scholar who takes her work as their subject. Inner and Outer Worlds, a collection of essays edited by Anthony Uhlmann, steps up to this challenge.

... (read more)The Beauty of Baudelaire: The poet as alternative lawgiver by Roger Pearson

The life and work of Charles Baudelaire (1821–67) must be viewed against the historical background of the crushing failure of the Paris revolution of 1848, in which soldiers massacred three thousand workers. In the elections that followed this unsuccessful working-class uprising, which Baudelaire and his fellow artists supported, the French Romantic poet Alphonse de Lamartine received 18,000 votes, while Louis Napoleon received fifteen million.

... (read more)When Susan Varga made the momentous, long-delayed decision to commit herself to writing, her first task was to write her mother’s story – that of a Holocaust survivor who migrated from Hungary to Australia with her second husband and two daughters in 1948, when Susan was five. That story, which is also one of a complex and difficult relationship between mother and daughter, became the award-winning Heddy and Me (1994).

... (read more)Essays Two: On Proust, translation, foreign languages, and the City of Arles by Lydia Davis

Lydia Davis writes long essays and short stories; some of them, like this one of six words, very short indeed: ‘INDEX ENTRY: Christian, I’m not a’. Influenced by Kafka and Beckett, she is drawn to Anglo-Saxon words, complex sentences, and literary forms which are hard to define. In the United States she has been awarded Guggenheim and MacArthur Genius Grants; in France she is a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters; in the United Kingdom she won the 2013 Man Booker International Prize for what Christopher Ricks, chair of the judges, called her ‘vigilance … to the very word or syllable’. Rick Moody calls her ‘the best prose stylist in America’, The New York Times compares her precision to that of Vermeer, while for her publisher she is simply ‘beyond compare’. Claire Messud, looking for fresh adulatory epithets, says that Lydia Davis ‘has the gift of making us feel alive’. What, then, am I missing?

... (read more)The Red Witch: A biography of Katharine Susannah Prichard by Nathan Hobby

Katharine Susannah Prichard is one of those mid-century Australian literary figures like Vance Palmer whose name is mentioned in literary histories more often than her books are read. As it happens, she was a schoolfriend of Vance’s future wife, Nettie, née Higgins, who became a distinguished literary critic, as well as of the pioneering woman lawyer Christian Jollie Smith, and Hilda Bull, later married to the playwright Louis Esson. All were politically on the left as adults, and Prichard and Jollie Smith joined the Communist Party. It was the distant Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917 that converted Katharine to the communist cause; she was a communist in Western Australia before there was a party there for her to belong to.

... (read more)Cacaphonies: The excremental canon of French literature by Annabel L. Kim

Freud once argued that the pleasure of shit is the first thing we learn to renounce on the way to becoming civilised. For Freud, the true universalising substance was soap; for Annabel L. Kim it is shit; and French literature is ‘full of shit’, both literally and figuratively, from Rabelais’s ‘excremental masterpieces’ Pantagruel and Gargantua and the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom through the latent faecality of the nineteenth-century realists to the canonical writers of French modernity.

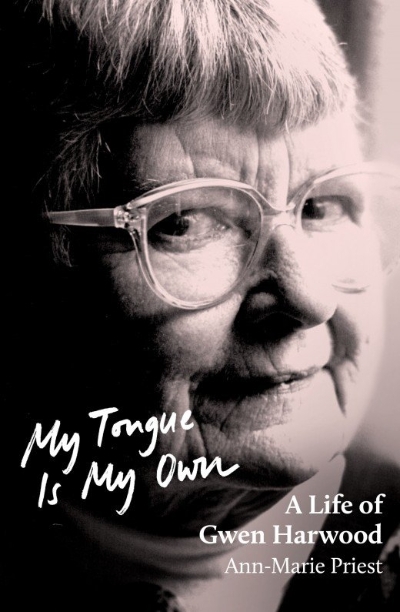

... (read more)When Ann-Marie Priest wrote to me in 2015 asking whether she might talk to me about her proposed biography of my mother, and requesting my permission to examine some correspondence in the Fryer Library, which I, as Gwen Harwood’s literary executor, had placed on restricted access, I replied with a terse refusal to cooperate. Since my mother’s death in December 1995, I had kept tight control of her vast correspondence, nearly all of which she had donated to various research libraries over the last two decades of her life, and I saw no reason to change my ways.

... (read more)My Tongue Is My Own: A life of Gwen Harwood by Ann-Marie Priest

The Red Queen’s impossible rule offers a striking allegory of the biographer’s dilemma. While your subject is still alive, it seems reasonable to get to know them and build a relationship of trust with them. In this way you might be better able to understand their private and intimate worlds. If your subject is a writer, you might become more confident in your ability to weave closer correspondences between their life and work. But if you then become privy to their secrets, and perhaps even come to love them as a dear friend, it becomes almost impossible to write about them dispassionately: to ‘cut’ them with your knife and fork.

... (read more)