Biography

The last institution of old Collingwood, the Collingwood Football Club, is poised to take flight from yuppified terraces in the former industrial suburb or new headquarters, on the site of what was once John Wren’s motordrome, Olympic Park. Now is a perfect moment in which to read this intriguing story of the one-time patron of Collingwood’s football, politics and gambling – Its masculine working-class culture, more or less. Published fifty-one years after Wren’s death, will Griffin’s biography finally allow the ghosts – not of Collingwood, but of its fictional shadow, the Carringbush of Frank Hardy’s Power Without Glory (1950) – to rest? Probably not.

... (read more)Very Big Journey: My life as I remember it by Hilda Jarman Muir

In her recently published collection of critical writing by indigenous Australians, Michele Grossman notes that ‘[s]ince the early 1980s, the burgeoning interest in and publication of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writing …has become increasingly well-established’. This is particularly true when we consider the success of life-writing by Aboriginal women in the last twenty years. Sally Morgan is practically a household name, and even the once-maligned work of Ruby Langford Ginibi has taken its place on school reading lists around the country.

... (read more)Do John and Janette choke on their cereal at the name of Robert Manne as they breakfast in their harbourside home-away-from-home? They have every reason to do so. No single individual has provided so comprehensive a challenge to Howard and his ideological claque in the culture wars now raging in this nation. Manne was early to denounce Howard: for his soft-shoe shuffle with Pauline Hanson; for the inhumanity of the government’s approach to the boat people; for the shallow basis for our participation in the Second Iraq War. In the wider war, he wrote a savage critique of the right-wing cognoscenti who assailed Bringing Them Home, and he has rallied the troops to repel Keith Windschuttle’s revisionist history of black–white confrontation in nineteenth-century Australia. Now he has edited this selection of essays, which provides a critical survey of the Howard government across a wide range of its policies.

... (read more)Alfred Felton, bachelor who lived for many years in boarding houses of one kind or another, might seem a familiar Victorian figure, particularly in a colony where there were not enough women to go around. But Felton was a bachelor with a difference. In the first place, as the co-founder of the prosperous drughouse Felton, Grimwade and Co., he was a colonial success story. He also had interests beyond business. His rooms at the Esplanade Hotel in St Kilda, where he spent his last years, were crammed with paintings, books and objects; some splendid, recently unearthed photographs document this ‘obsessive profusion’, as John Poynter describes it.

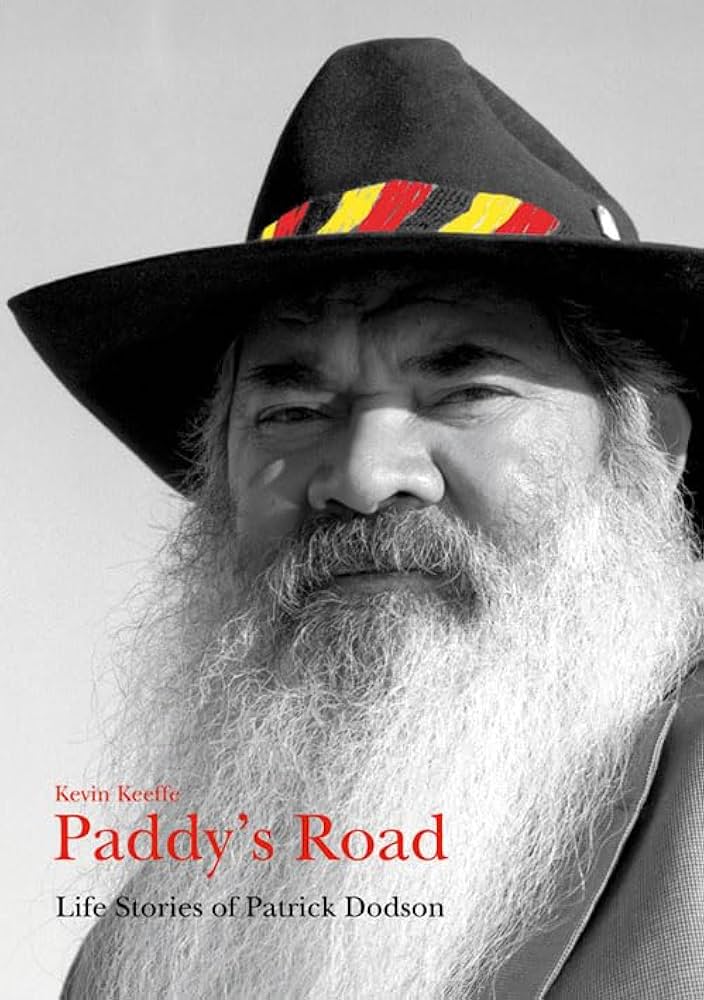

... (read more)Paddy's Road: Life stories of Patrick Dodson edited by Kevin Keeffe

For many Australians, Patrick Dodson is the guy with the land rights hat and flowing beard. With Paddy’s Road: Life stories of Patrick Dodson, Kevin Keeffe ensures that Dodson will also be remembered for being the first Aboriginal priest and for his contributions to the reconciliation movement.

... (read more)Paddy's Road: Life Stories of Patrick Dodson by Kevin Keeffe

For many Australians, Patrick Dodson is the guy with the land rights hat and flowing beard. With Paddy‘s Road: Life Stories of Patrick Dodson, Kevin Keeffe ensures that Dodson will also be remembered for being the first Aboriginal priest and for his contributions to the reconciliation movement.

More a homage than a warts-and-all tale, Keeffe’s tome contains numerous feel-good and funny moments. For example, we learn that Dodson, the so-called ‘father of reconciliation’, was born in a laundry toilet, ‘nearly drowning in the Phenyl used for cleaning the ... pans’; and that Patrick’s grandfather, Paddy Djiagween, claimed his citizenship rights in person. ... (read more)Shadow of Doubt: My Father and Myself by Richard Freadman

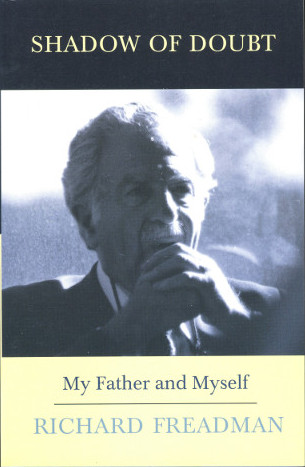

Richard Freadman’s first work intended for a non-academic readership is, in his own words, ‘the Son’s Book of the Father’ and thus belongs to a venerable genre. Freadman, whose contribution to our understanding of autobiography has been acute, is well qualified to draw on this tradition in portraying his own father and analysing their relationship. Along the way, he discusses memoirists such as John Stuart Mill, Edmund Gosse and Henry James.

Shadow of Doubt: My Father and Myself can’t have been an easy book to write. Few family memoirs are, if their authors are honest about their families and themselves. Freadman knows that autobiography is a ‘chancy recollective escapade’. ‘My father,’ he writes, ‘was an extremely, an impressively complex man, and there is no single “key” to a life like this.’

... (read more)George Orwell, born in 1903, was the child of a British Empire civil service family with long Burmese connections, which belonged, as he put it with characteristic precision and drollery, to the lower upper middle class. By the time he went to fight against fascism in Spain in 1936, he had already quit his job in the Burmese colonial police, attempted to drop out of the English class system, and become a writer and a socialist of a notably independent, indeed idiosyncratic, kind.

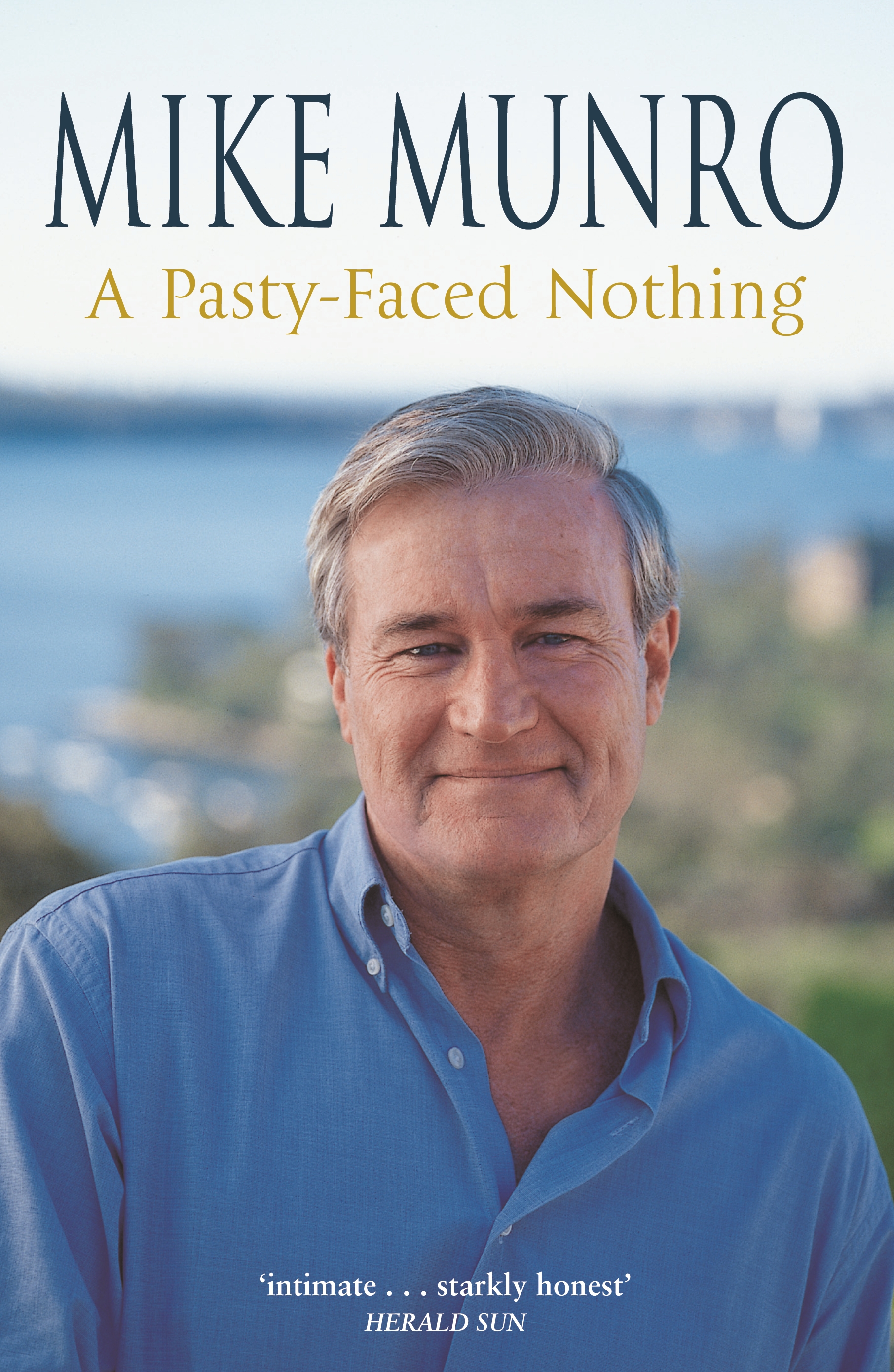

... (read more)I must confess I picked up this celebrity autobiography, complete with embossed cover and a price suggestive of a huge print run, without anticipation. I could not have been more wrong. Mike Munro’s excoriating and frank account of his abused childhood and early years in journalism chronicles a survival story that is Dickensian in scope and impact. Like Dickens, Munro managed to overcome poverty, cruelty and emotional deprivation to reach the top of a demanding profession. Remarkably, considering his scarifying experiences as a child and adolescent, he fell in love and married a partner with whom he has created the kind of loving family life that he never knew as a child. But I am jumping ahead.

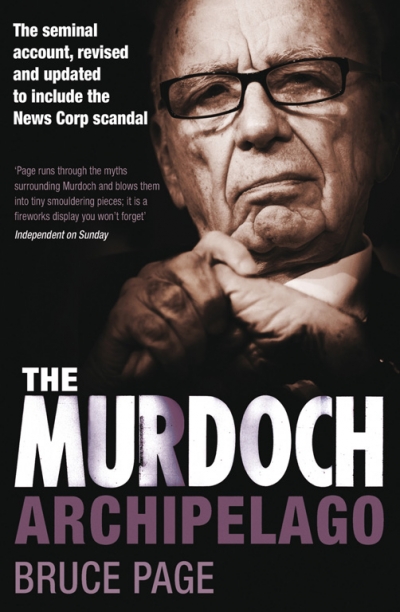

... (read more)Rupert Murdoch certainly attracts a good class of biographer. There was George Munster, who contributed so much to Australian politics and culture by helping to establish and edit Nation, and William Shawcross, one of Britain’s most prominent journalists. There were other biographies, too, before the efforts of Bruce Page ...

... (read more)