Biography

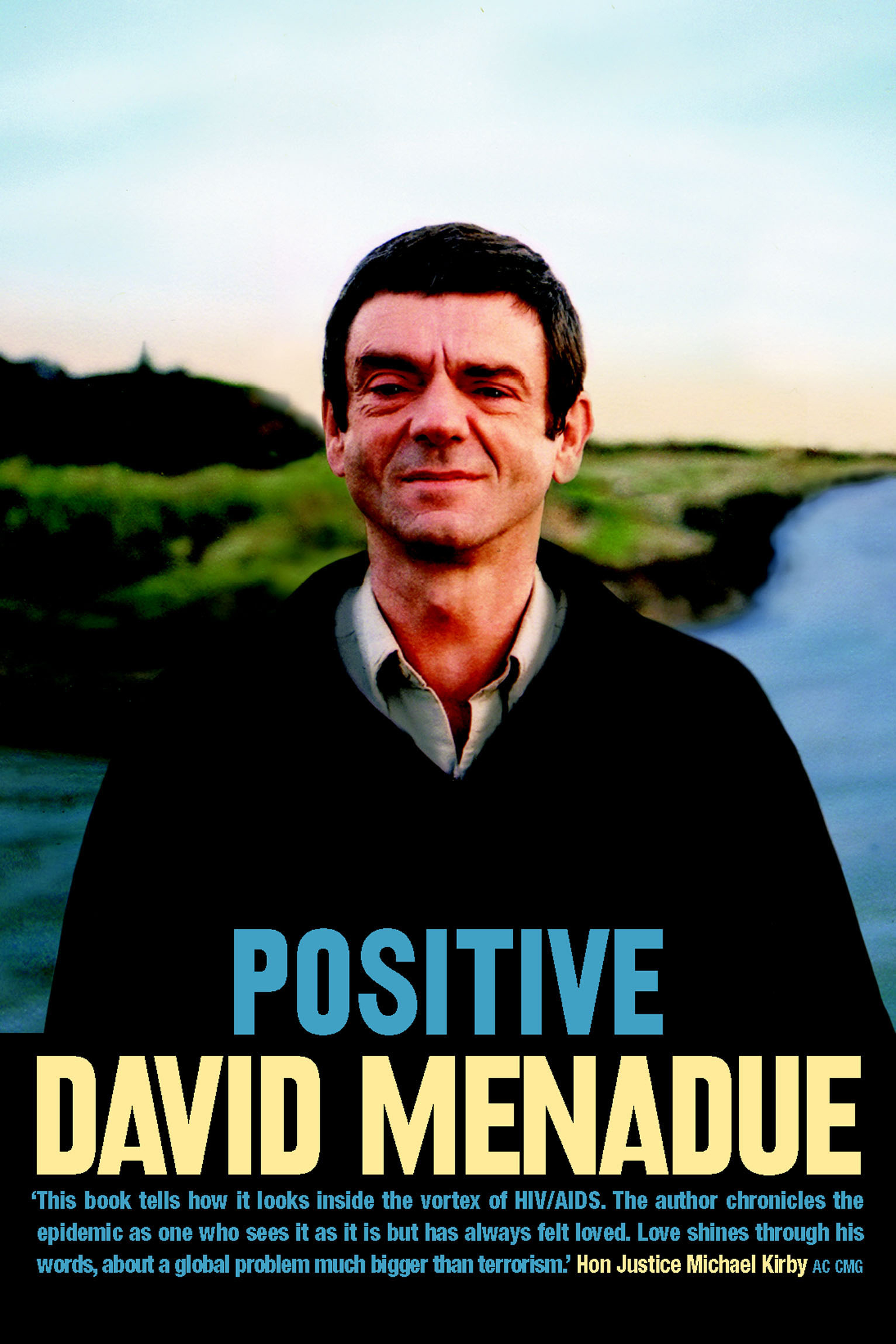

In the Australian world of HIV/AIDS, David Menadue is something of a legend. He tested positive to HIV in 1984, and first became ill with AIDS in 1989. This makes Menadue one of the longest-term survivors of an AIDS-defining illness in Victoria. As his doctors note, and as he reaffirms, not without a hint of justifiable pride, ‘this is a remarkable record … my survival is exceptional’. Equally exceptional is Menadue’s optimism. ‘I have always been an optimist,’ he writes, ‘and even in my darkest days with AIDS, I don’t think I ever gave up hope.’ This is how Menadue accounts for his longevity – a mix of optimism, hope and good fortune. The reader might also add courage.

... (read more)What Australia Means to Me by Bob Carr & Bob Carr by Andrew West and Rachel Morris

Not since Henry Parkes has New South Wales had such a literary-minded premier as Bob Carr. Parkes published his own poems and wrote two earnest volumes of autobiography. Carr, so far, has tried his hand at a novel, a memoir and a diary, as well as writing lots of occasional pieces. Carr, like Parkes, was a journalist before becoming a professional politician. Parkes, too, dragged himself from humble beginnings to a position where he could use official letterhead to arrange meetings with those he admired. Carr has sought out writers such as Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal to autograph his copies of their books and to join him at dinner. Once established, Parkes’s main aim was to stay in power. It was his only source of income, so his manipulation of factions, policies and the electorate all focused on that end. Graham Freudenberg has said of Carr: ‘Labor politics is central to Bob’s identity … if you took the politics away from Bob there would be nothing much left.’ But unlike Carr, Parkes did not have the option of moving to federal politics (he died before 1901). After Federation, NSW politics was stripped of talent as its leaders, including Edmund Barton, William Lyne and George Reid, made the move. Reid, a long-serving and highly effective NSW premier, is one of only two state premiers ever to have succeeded in becoming prime minister, the other being Joe Lyons.

... (read more)In 1519 the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortés marched into Tenochtitlán (Mexico City), heart of the Aztec Empire. Thus began the often tragic history of European colonialism in the Americas. Anna Lanyon’s previous book, Malinche’s Conquest (1999), retraced and recovered the extraordinary life of Cortés’s translator and lover, the native American woman Malinche. The present book does the same for their child, Martín Cortés.

... (read more)Not one word is wasted in Sir Nicholas Shehadie’s memoir, A Life Worth Living. Almost all the words are. This book is a triumph of lack of style over lack of substance. It’s a pity to attach such a proud word as ‘book’ to a publication like this, as it is to attach ‘music’ to two-fingered renditions of Chopsticks. Shehadie is no writer, nor does he pretend to be, which is a shame. A little pretence might have tricked up the work from being a tedious CV to a worthy member of Australia’s naïve school of sports memoirs, the current champion of which is Dawn Fraser’s energetic Dawn: One Hell of a Life (2001), with its patches of vivid, detailed recollection and clean, functional prose.

... (read more)The Trial of the Cannibal Dog: Captain Cook in the South Seas by Anne Salmond

From 1768 until 1779–80, in a series of remarkable voyages of circumnavigation, Captain James Cook ‘fixed the bounds of the habitable earth, as well as those of the navigable ocean, in the southern hemisphere’. During these voyages, Cook sailed further, and further out of sight of land, than anyone had previously done. He discovered – or rediscovered – numerous islands. He demonstrated how the new ‘time keeper’ (chronometer) might be used to determine longitude much more accurately than ever before. He showed how scurvy might be controlled. He encountered and left detailed descriptions of peoples about whom Europeans had little or no knowledge. The scientists who sailed with him made very extensive collections of birds, animals, fish and plants, and obtained a wealth of information about the atmosphere and the oceans, all of which contributed significantly to the emergent modern scientific disciplines. In short, as one of his companions observed after his death, ‘no one knew the value of a fleeting moment better and no one used it so scrupulously as [Cook]. In the same period of time no one has ever extended the bounds of our knowledge to such a degree.’

... (read more)Assuming the Chair of a business regulatory authority might not be thought of as an ideal path to media stardom, but Allan Fels showed otherwise. Fels is easily Australia’s best-known cartel buster and the scourge of price-fixing business and anti-competitive behaviour generally. For years he was regularly on the nightly news. In a savage sea of rapacious price-gougers, Fels was the consumer’s friend.

... (read more)Man of Honour: John Macarthur – duellist, rebel, Founding Father by Michael Duffy

As I read this book, serious questions were being asked about the honour of three governments: the British, the US and our own. Did they all lie so as to justify war against Iraq? Honour still matters, even at a time when the word is not used as often as it once was. Michael Duffy’s book about John Macarthur, one of the best-known inhabitants of colonial Australia, constructs him as a ‘man of honour’. It ought to be topical.

... (read more)The Pope’s Battalions: Santamaria, Catholicism and The Labor Split by Ross Fitzgerald

Ross Fitzgerald’s book is timely, for two reasons. Five years having passed since the death of B.A. Santamaria, an appropriate distance stands between the immediate obituaries and a better perspective on his impact on Australian politics. It is also nearly fifty years since the great Labor schism. A new generation of Australians has grown up for whom ‘The Split’ is not part of the political lexicon. The Pope’s Battalions reminds one of a time when this term required no explanation, just as ‘The Dismissal’ needs no explanation to Australians over a certain age.

... (read more)The Man Who Saw Too Much: David Brill, Combat Cameraman by John Little

Despite Jeff McMullen’s assertion in the foreword to The Man Who Saw Too Much that books like this are rare, this is in fact the latest in a long line of books about Australian war and foreign correspondents, by which I mean photographers, cameramen and women, and cinematographers (the term preferred by David Brill), as well as journalists. In recent times, books by, or about, the adventurous boys – Damien Parer and Neil Davis (both role models for Brill), Richard Hughes (whom Brill met in later life), Wilfred Burchett and Hugh Lunn – have, thankfully, been joined by autobiographies of women journalists such as Irris Makler.

... (read more)In Paradise Mislaid, Anne Whitehead captivated readers with a nicely judged blend of elements. Here was a documentary that interwove two travellers’ tales, each with the resonance of quest narratives. Those ‘peculiar people’ who went off to Paraguay as part of William Lane’s experimental Utopian settlement were seeking a just community where the labourer would not only be worthy of his hire, but actually receive it; while Whitehead was pursuing the historian’s endless quest to bring back into present memory the always receding reality of the past. But Whitehead’s journey was not made only in the mind or in the archives: it had a literal dimension, involving following physically ‘in the steps of’ her subject. This led to an interesting relationship between past and present in her work, a layered intercutting, sometimes positing connection, sometimes disjunction. The effect was analogous to the intercutting techniques of documentaries, and it’s not surprising to find that Whitehead has worked extensively as television producer, film director and scriptwriter. It also offered, in a way, a gentle rebuff to any undeconstructed readerly yearning for the complete and logically sequential narrative that we might once have thought history could give us.

... (read more)