Fiction

The Sunken Road is an ambitious novel which sets the crisscrossing lives of families in the northern highlands of South Australia against a temporal panorama of a century and a half and forces that extend far beyond state and continent. It is a compassionate but never sentimental account of a collective experience full of hope, pain, exploitation and double standards. At its centre is a strongly rendered character called Anna Antonia Ison Tolley.

... (read more)Fiona Capp’s accomplished first novel is pungent with sea-salt and urgent with the relentless momentum of the waves. It opens with the image of tsunami, a freak wave that grows from a shudder in the seabed to a wall of ocean which engulfs the landscape of the novel, an image which is recalled most effectively through the book to echo in metaphor the emotional upheavals of its characters.

These characters are strongly but sparely drawn: we meet them over a summer holiday season and learn little more of them than is necessary to give each motivation and convincing life. Hannah is a year into Melbourne University; commended all her life for having her feet firmly on the ground, she ‘dreams of walking on water’ and has come down the Mornington Peninsula with a secondhand surfboard to try to make the dream into one kind of reality. Marcus and his son Jake fled to the Peninsula from the Liverpool docks, putting distance between themselves and the pain of Jake’s mother’s death from cancer. Jake surfs under the jealous mentorship of a polio-stunted science teacher and Marcus collects the detritus and the distinctive treasures that the sea spews up along the tideline.

... (read more)Until I reviewed Marion Halligans novel Lovers’ Knots, I didn’t really know much about what a lover’s knot was. And now I know more than I used to know about the word ‘cockle’.

... (read more)White Guard by David Clunies-Ross & A Good Time To Die by James Tatham

David Clunies-Ross came under notice last year with Springboard, a darkly intriguing thriller about power, corruption and murder in Hong Kong at a nervous time in the colony’s history, with the Chinese takeover looming. In White Guard he seems to have used the same ingredients to assemble a similar scenario about Australia on the brink of becoming a republic as the year 2000 approaches. Domestically, the country’s politics are in disarray, bringing to mind the constitutional crisis of 1975. Couldn’t happen again, could it? Simultaneously, superpowers are competing in a deadly game of brinkmanship that shows up the threat to this country’s very existence in the form of US communications bases at Pine Gap, Nurrungar and the North West Cape – But Skinner’s position is clearly untenable: he has put the US offside by threatening not to renew leases for its tracking bases, right on the eve of a major joint military exercise in the outback; the Opposition is hugely popular with voters and Skinner has a sex scandal hanging over his head which will destroy him if it gets in the papers. Something’s got to give, but Skinner’s determined to hold on to power no matter what, as politicians invariably are for some reason.

... (read more)Marilyn's Almost terminal New York Adventure by Justine Ettler

Marilyn’s Almost Terminal New York Adventure offers all the ingredients that have made Justine Ettler’s name to date: sex, drugs, tough women, bad men, and rough prose. Thankfully it does leave behind some, though not all, of the relentless violence of The River Ophelia. Marilyn is not as hell-bent on the same masochistic path as Ettler’s earlier heroine, Justine, and the novel admits a lightness of tone which is initially refreshing.

... (read more)It is always a pleasure to read Glenda Adams, a most accomplished and stylish writer. At its best her work displays a natural and unassuming flow, masking artistry of a high order. Admirers of her earlier books will find many familiar concerns in The Tempest of Clemenza; they will also discover her striking out in new directions in a bold and adventurous undertaking.

... (read more)This amazing novel comes in two parts, a 431-page prose Saga, and a 123 page verse Ballad. The whole is held together by a Narrator, who tells the Saga as a gloss on the Ballad, which he found in an old bike shed in an abandoned mailbag. The ballad was written by Orion the Poet, a young man called Timothy Papadirnitriou ...

... (read more)How do you give a plot description of this book without entering into the very language that it problematises? Ari is young, unemployed, Greek and gay ... Or Ari is a poofter wog, a slut, a conscientious objector from the workforce ...

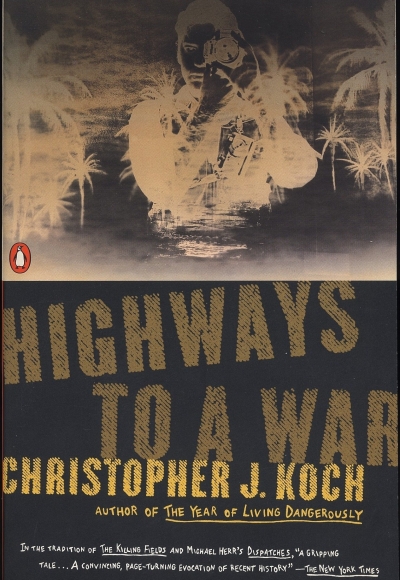

... (read more)Vietnam, of all the foreign conflicts in which Australians have been involved, most outgrew and out lived its military dimension. The ghosts of what Christopher J. Koch in this new novel calls ‘that long and bitter saga’ continue to haunt the lives (and the politics) of the generations of men and women who lived through it ...

... (read more)With his third novel, Billy Sunday, Rod Jones would appear to have affirmed an intention – an unexpressed intention, admittedly – never to be considered a contender for the Miles Franklin Award. Julia Paradise (1986), while located principally in Shanghai, did after all relocate itself in northern Queensland. Prince of the Lilies (1991) boasted an Australian protagonist while being set firmly on Crete. Billy Sunday is set, however, in late nineteenth-century Wisconsin and has as protagonist and deuteragonist the historical figures of Frederick Jackson Turner, historian, and Billy Sunday, charismatic evangelist. Rod Jones may not be a Miles Franklin contender – given last year’s eligibility shambles, and one judge’s opinion that Bruce Chatwin’s Songlines might have been considered in a previous year, it is hard to imagine why any novelists would submit themselves to the indignity of being considered – yet he may, on the other hand, have written the Great American Novel.

... (read more)