NewSouth

Fantasy Modern: Loudon Sainthill's Theatre of Art and Life by Andrew Montana

by Lee Christofis •

The Best Australian Science Writing 2013 edited by Jane McCredie and Natasha Mitchell

by Danielle Clode •

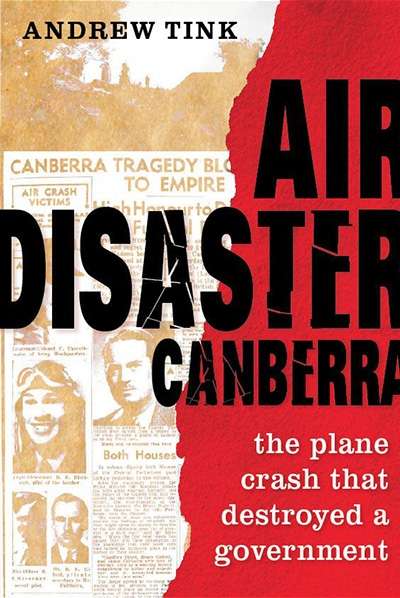

Air Disaster Canberra: The plane crash that destroyed a government by Andrew Tink

by Lyndon Megarrity •

The Best Australian Science Writing 2012 edited by Elizabeth Finkel

by Robyn Williams •

The Best Australian Business Writing 2012 edited by Andrew Cornell

by Gillian Terzis •

JJ Clark: Architect of the Australian Renaissance by Andrew Dodd

by Philip Goad •

Whackademia: An Insider’s Account of the Troubled University by Richard Hil

by Suzie Gibson •