Natural History

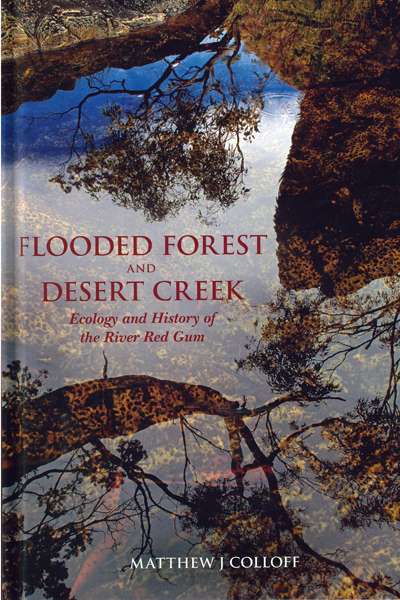

Flooded Forest and Desert Creek: Ecology and history of the River Red Gum by Matthew J. Colloff

by Ruth A. Morgan •

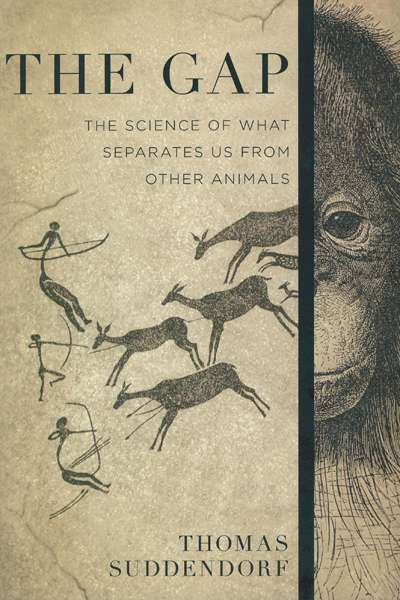

The Gap: The Science of What Separates Us From Other Animals by Thomas Suddendorf

by Robyn Williams •

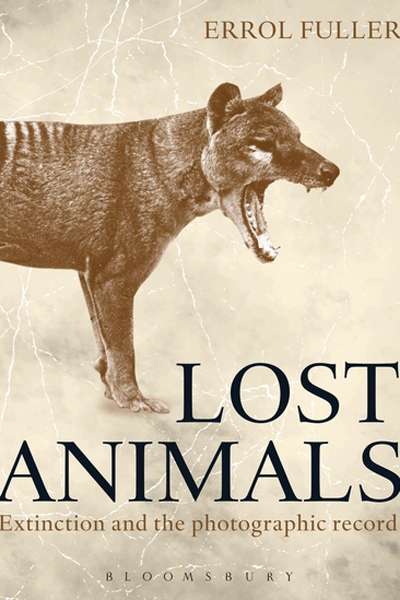

Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record by Errol Fuller

by Peter Menkhorst •

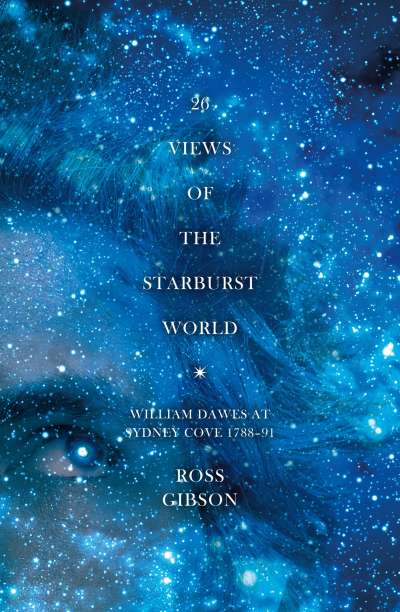

26 Views of the Starburst World: William Dawes at Sydney Cove 1788–91 by Ross Gibson

by Andy Lloyd James •

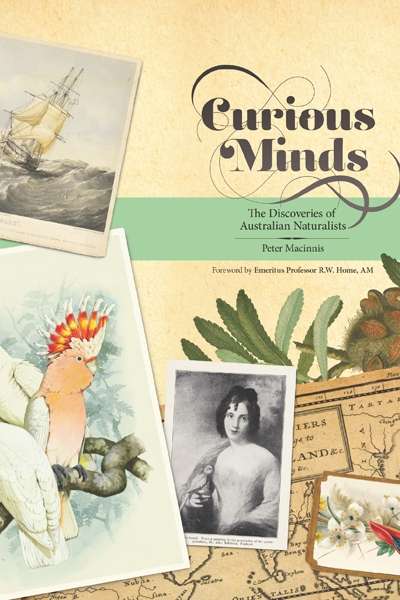

Curious Minds: The Discoveries of Australian Naturalists by Peter Macinnis

by Peter Menkhorst •

Sentinel Chickens: What Birds Tell Us about Our Health and the World by Peter Doherty

by Peter Menkhorst •