Translations

Why does translation matter? Or does it? And who should care to know? The answers are more interesting than we might at first think. The filming of a novel, and a multinational company’s diverse advertising strategy for the one product in different countries, involve issues of translation just as much as an English version of a sonnet by Petrarch. These days, translation has outgrown its status as an illegitimate child of literature, to become a way of discussing any exchange between languages and cultures, and appropriately so, given that the word itself derives from the Latin translatio, which simply means ‘carried across’.

... (read more)At the moment, there are about 5,000 world languages, and ninety per cent of these languages are spoken by about five per cent of the world’s population. A pessimistic forecast would predict that by 2,100 only 500 of these languages will still exist; an optimistic forecast might put the figure at 2,500, about the same rate as the extinction of mammals. Many of the languages under threat are spoken in countries that are close to Australia: Papua New Guinea has 850, Indonesia 670, and India 380. (Australia is listed as still having 200, but many Australian linguists would put this figure much lower.) It is a relatively easy matter to rally the troops, the money and the organisational forces to attempt to save furry mammals; it is a much more difficult matter to rally support to save languages. This book, by the eminent French linguist Claude Hagège, assesses how and why languages die, what the cost of their deaths is, and whether anything can be done to prevent their annihilation.

... (read more)Stepping Out: A novel by Catherine Ray, translated by Julie Rose

Faced with the publication of her first novel, the narrator of Stepping Out has a terrifying thought. ‘I was about to be unmasked,’ she realises. ‘End of my double life. Everyone was about to dip into my world and find out what was really cooking there ... I felt like I’d placed a bomb and was waiting, under cover, for it to explode.’

... (read more)The Shorter Poems of Gaius Valerius Catullus by Gaius Valerius Catullus, translated by A.D. Hope

Gaius Valerius Catullus (c.87–54 BC) may have died young, but his limited output (only 113 poems and some fragments have survived) has immortalised him as a writer of erotic and satiric verse and savage portraits of contemporaries, so frank sometimes that, until recent decades, editions of his work were customarily heavily expurgated. Innumerable poets through the ages have kept his flame burning. Ezra Pound peppers the opening cantos with references to Catullus. Ben Jonson’s famous ‘Come, my Celia’ is a version of Catullus 5.

... (read more)Translating Lives: Living with two languages and cultures edited by Mary Besemeres and Anna Wierzbicka

Language shapes identity: everyone knows that, in theory. Anyone who has studied a foreign language knows that exact equivalents do not exist for every word. Translation cannot be perfect: something is always lost. So what happens when people, used to one linguistic identity, have to translate themselves into a new language? Mary Besemeres and Anna Wierzbicka have assembled twelve witnesses to give personal accounts. All are academics or writers who possess the intellectual resources to make sense of what they have encountered, while at the same time registering the dislocations they have experienced. All write English fluently: they are not concerned with the difficulties of learning English but of being themselves in Australian English. Some make the comment that they are perfectly comfortable writing academic English while still finding the small transactions of daily life a challenge.

... (read more)The world we live in provides us with a great deal of information that is not really intended to inform. We must be informed, for example, that a phone call is being recorded for training purposes. Thus language becomes an accessory to the black arts of spin, propaganda, manipulation and arse-covering. Words are twisted and violated, making it difficult to recover the meanings, the distinctions, that we need. What was clear becomes murky, while murkiness is hidden behind a veneer of false clarity. Protean language becomes complicit in the world’s nefarious purposes.

... (read more)After the longest of waits, French film scholar and militant cinéphile Nicole Brenez has finally had a book translated into English (it appears in the Contemporary Film Directors series). For those of us who don’t read French, this is exciting news: Brenez’s rigorous engagement with what she calls the history of forms has until now only been available to us piecemeal, spattered across the hyperlinked pages of online film journals such as Rouge and Senses of Cinema. To find ourselves able to read a full-length monograph – on one of the greatest and most shamefully overlooked film-makers of our times – should be cause for celebration in film departments everywhere. (That it probably won’t be is another matter entirely.)

... (read more)What’s a nice girl called Anastasia doing in the Whangpoa River? Maybe she’s the daughter of the last tsar who everyone thought was dead, or maybe it’s just a girl who looks like a Russian princess and happens to have the same name. If the proposition sounds familiar, be assured by Colin Falconer that Anastasia Romanovs were thick on the streets of Shanghai after the White Russian diaspora of 1917–18.

... (read more)The Child of an Ancient People by Anouar Benmalek (translated by Andrew Riemer)

At once extravagant and tightly wrapped, this novel reinforces the view that historical fiction says as much about the present and the future as it does about the past. At the level of history proper, Anouar Benmalek’s vision unites three continents that, in the second half of the nineteenth century, are subject to the depredations of European colonialism and domestic tyranny. At the human level, his fiction is preoccupied with the bodily functions and basic needs of survival: things that never change. The broad, impersonal sweep of world history is made up of the infinitesimally small transactions of the primal scene: copulating, defecating, vomiting, bleeding, all driven by the elemental forces of fear and desire, violence and conscience.

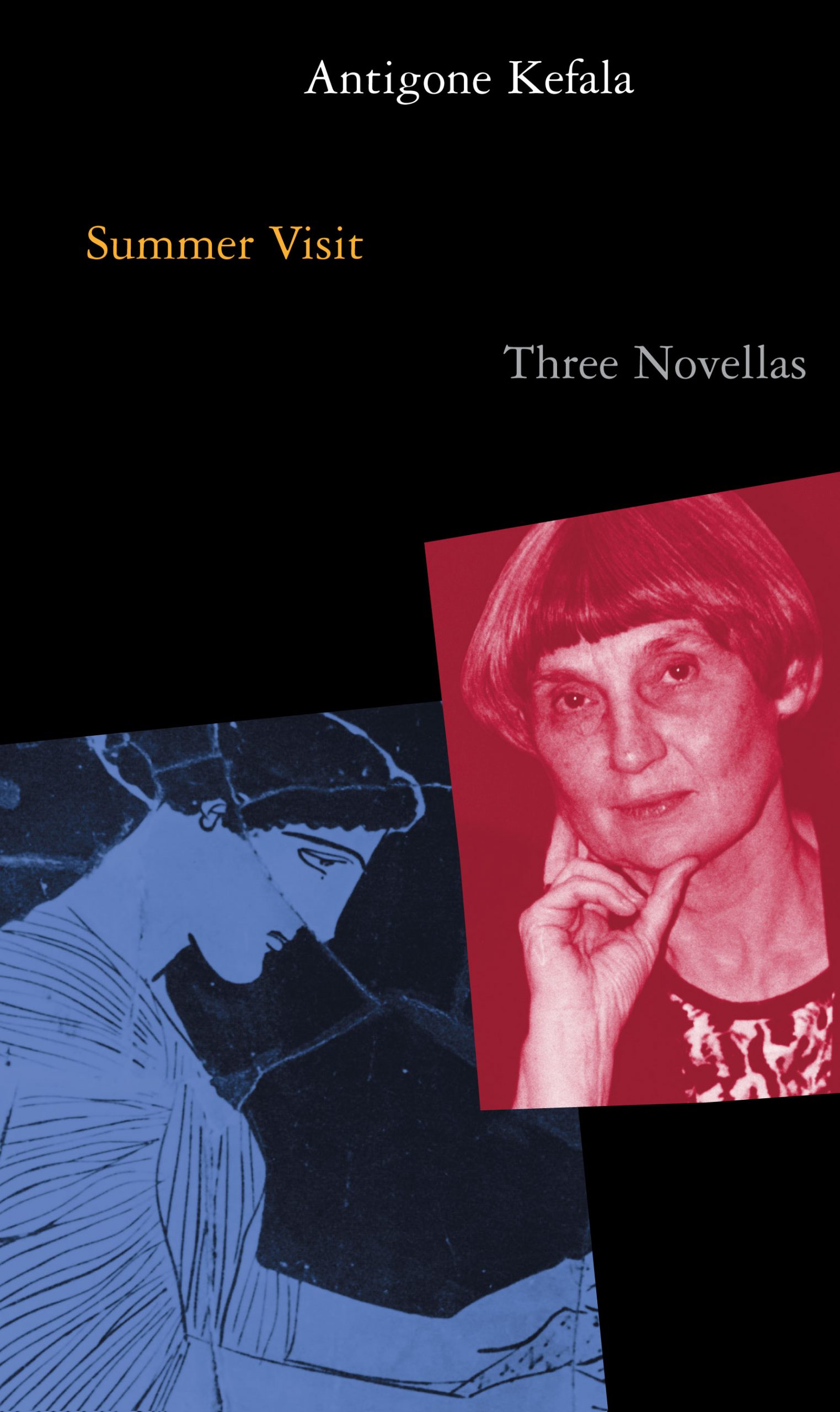

... (read more)Summer Visit by Antigone Kefala & The Island/L’île/To Nisi by Antigone Kefala

Readers who share Helen Nickas’s view that Antigone Kefala’s fiction forms ‘a continuous narrative which depicts and explores the various stages of an exilic journey’ may be pleased to find more instalments in her fourth book of fiction, Summer Visit. The first of the three novellas is an account of an unsatisfying marriage, told with a controlled detachment that makes its title, ‘Intimacy’, seem ironic. In contrast, the third, ‘Conversations with Mother’, contains a series of elegiac apostrophes of the deceased; the connections with Braila and other congruities with a figure familiar from previous writings again encourage an assumption of autobiography.

... (read more)