Allen & Unwin

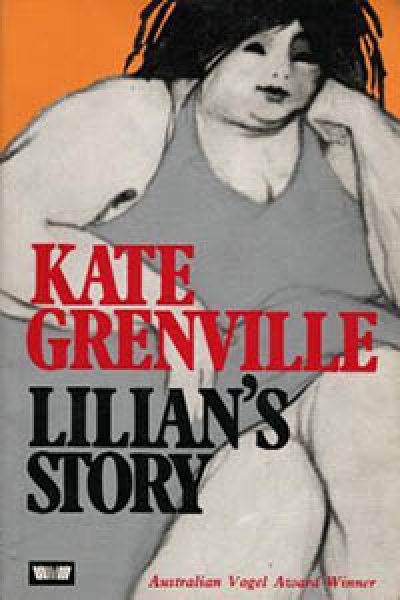

Lilian’s Story by Kate Grenville & Bearded Ladies by Kate Grenville

by Marian Eldridge •

Surrender Australia?: Essays in the study and uses of Australian history edited by Andrew Markus and M.C. Ricklefs

by James Jupp •

Shallows by Tim Winton & Goodbye Goldilocks by Judith Arthy

by Nancy Keesing •

Birds of Passage by Brian Castro & Getting Away With It by Kevin Brophy

by Graham Burns •

Australia Since the Coming of Man by Russel Ward & New History edited by G. Osborne and W.F. Mandie

by L.L. Robson •