Memoir

More than twenty-five years ago, I wrote an essay on the work of Oliver Sacks (Island Magazine, Autumn 1993). Entitled ‘Anthropologist of Mind’, it ranged across several of Sacks’s books; but it was Seeing Voices, published in 1989, that was the main impetus for the essay. In Seeing Voices, Sacks explored American deaf communities, past and present. He exposed the stringent and often punishing attempts to ‘normalise’ deaf people by forcing them to communicate orally, and he simultaneously deplored the denigration and widespread outlawing of sign language. Drawing on the work of Erving Goffman, Sacks showed how deaf people were stigmatised and marginalised from mainstream culture, and he revealed, contrary to prevailing opinion in the hearing world, the richness and complexities of American Sign Language.

... (read more)Alison Croggon has written poetry, fantasy novels, and whip-smart arts criticism for decades, but Monsters is her first book-length work of non-fiction. In this deeply wounded book, Croggon unpacks her shattered relationship with her younger sister (not named in the book), a dynamic that bristles with accusations and resentments. In attempting to understand the wreckage of this relationship, Croggon finds herself going back to the roots of Western patriarchy and colonialism, seeking to frame this fractured relationship as the inexorable consequence of empire.

... (read more)No Document begins with a description of the opening sequence of Georges Franju’s Le Sang des bêtes (Blood of the Beasts, 1949) in which a horse is led to slaughter – a significant misremembering that Anwen Crawford rectifies later. Franju’s black-and-white documentary actually begins with a collage of scenes shot on the outskirts of Paris; surreal juxtapositions of objects abandoned in a landscape devastated by war and reconstruction.

... (read more)In 2005, Murray Bail published Notebooks: 1970–2003. ‘With some corrections’, the contents were transcriptions of entries Bail made in notebooks during that period. Now, in 2021, dozens of these entries – observations, quotations, reflections, scenes – recur in his new book, He. It’s to be assumed that this book, too, is a series of carefully selected transcriptions from the same, and later, notebooks.

... (read more)Soar: A life freed by dance by David McAllister with Amanda Dunn

David McAllister, known affectionately as ‘Daisy’ to his fellow dancers, completed this memoir just as Covid-19 put paid to the exciting program he had devised for his final year as artistic director of the Australian Ballet. In spite of the cancelled world premières, McAllister makes no complaint about what must surely have been a disappointing finale to a stellar career, but he remains upbeat, turning his hand to modest ‘Dancing with David’ videos, alongside the company’s filmed performances and the Bodytorque.Digital program.

... (read more)Cathy Goes to Canberra: Doing politics differently by Cathy McGowan

‘Orange balloons. Orange streamers. Orange shirts.’ Cathy McGowan’s memoir is saturated and literally wrapped in the colour. Cathy Goes to Canberra begins with an account of the election of her independent successor as Member for Indi, Dr Helen Haines, in May 2019 – ‘with orange everywhere’.

... (read more)Paul Jennings’s literary career can be traced back to three whispered words from the author Carmel Bird, who taught him writing at an evening class in Melbourne in 1983. ‘You are good,’ she told him. Jennings was an unpublished forty-year-old at the time, yet within two years Penguin had launched his first short story collection, Unreal!

... (read more)‘A voyage round my father’, to quote the title of John Mortimer’s autobiographical play of 1963, has been a popular form of personal memoir in Britain from Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son (1907) to Michael Parkinson’s just-published Like Father, Like Son. The same form produced some of the best Australian writing in the twentieth century, with two assured classics in the case of Germaine Greer’s Daddy, We Hardly Knew You (1989) and Raimond Gaita’s Romulus, My Father (1998). The tradition has continued into the present century with – to list some of the choicest plums – Richard Freadman’s Shadow of Doubt: My father and myself (2003), Sheila Fitzpatrick’s My Father’s Daughter (2010), Jim Davidson’s A Führer for a Father (2017), and Christopher Raja’s Into the Suburbs: A migrant’s story (2020). Mothers in such sagas are far from absent, and they can emerge, though not always, as the more obviously loveable or loving figures. As signalled by most of those titles, however, mothers loom less large over the unfolding narrative. Fathers may not always know or act best, but, partly because of their often tougher, commanding mien, they become irresistibly the centre of attention.

... (read more)Barack Obama has written the best presidential memoir since Ulysses S. Grant in 1885, and since Grant’s was mostly an account of his pre-presidential, Civil War generalship – written at speed, to stave off penury for his family, as he was dying of throat cancer – Obama’s lays some claim to being the greatest, at least so far. This first volume (of two) only reaches the third of his eight years in the White House.

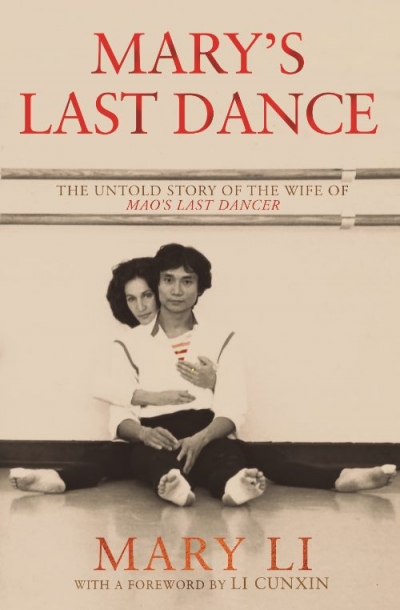

... (read more)Mary’s Last Dance: The untold story of the wife of Mao’s Last Dancer by Mary Li

The cover of this book tells you pretty much what to expect. It shows the dancer Li Cunxin, evidently at rehearsal, facing the camera while over his shoulder peeps his wife, Mary. Add the subtitle, that this is the ‘untold story’ of Li Cunxin’s wife, with a foreword by the man himself, and it’s clear that this book might not have seen the light of day without the phenomenal success of Mao’s Last Dancer, published in 2003 and later made into a well-received film (Bruce Beresford, 2009). Even the title has echoes of its predecessor.

... (read more)