Fiction

With Wolfe Island, Lucy Treloar joins a growing number of novelists whose fiction is marked by anthropogenic catastrophe. Her latest offering confronts two urgent global crises: the climate emergency, and the plight of refugees. Treloar reveals startling connections between the two through the shared thread of displacement in ...

... (read more)The sunset is orange, the sky scattered with clouds. We’re eating pumpkin and lentil soup out of bowls from home. I didn’t think it was necessary to bring them, the cupboards here are well stocked, but Irene insisted. She says they’re the perfect size. Also, she read in her online mother’s group that the glaze on old crockery often contains lead ...

... (read more)A bookseller, Trevor, sits in his shop in Melbourne making conversation with his customers: an exasperating mixture of confessional, hesitant, deranged, and disruptive members of the public. One man stalks him, armed with an outrageous personal demand; another tries to apologise for assaulting him. The apology is almost as unnerving as the attack ...

... (read more)Here Until August: Stories by Josephine Rowe & This Taste for Silence: Stories by Amanda O’Callaghan

The inciting incident in Josephine Rowe’s short story ‘Glisk’ (winner of the 2016 Jolley Prize) unpacks in an instant. A dog emerges from the scrub and a ute veers into oncoming traffic. A sedan carrying a mother and two kids swerves into the safety barrier, corroded by the salt air, and disappears over a sandstone bluff ...

... (read more)In The Old Lie, Claire G. Coleman has given herself a right of reply to her award-winning début novel, Terra Nullius (2007). Here, she strips away some of the racial ambiguity of the human–alien invasion allegory of that novel and leaves in its place a meaty analysis of colonisation and imperialism ...

... (read more)Do not attempt to judge this book by its amazingly beautiful but iconographically confusing cover. A close-up photograph of a single leaf shows its veins and pores in tiny detail. The colours are the most pastel and tender of creamy greens. Superimposed over this lush and suggestively fertile image is the book’s one-word title: Drylands ...

... (read more)In 2013, Matthew Condon published Three Crooked Kings, the first in his true crime series delving into the murky, sordid, and often brutal world of police corruption in Queensland. That year, he wrote in Australian Book Review that, after finishing his trilogy, he planned to ‘swan dive into the infinitely more comfortable genre of fiction’ ...

... (read more)Wiradjuri writer Tara June Winch is not afraid to play with the form and shape of fiction. Her dazzling début, Swallow the Air (2006), is a short novel in vignettes that moves quickly through striking images and poetic prose ...

... (read more)If the number of reviews and interviews are indicators of a new book’s impact, Tony Birch’s novel The White Girl has landed like a B-format sized asteroid. Birch’s publisher estimates a substantial number of reviews and other features since publication. I’ve consulted none of them ...

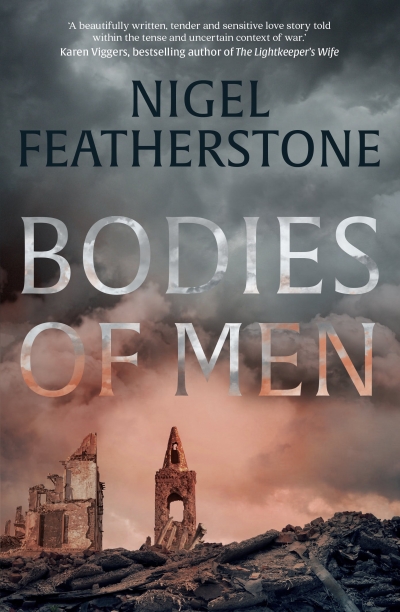

... (read more)From its raw and revelatory prologue, Nigel Featherstone’s novel Bodies of Men offers a thoroughly humanising depiction of Australians during World War II. In telling the story of two soldiers, William – too young to be a corporal – and his childhood friend ...

... (read more)