Fiction

At times I was delighted by this novel and at others was absolutely irritated. It is a novel which swerves between metaphors of wit and wisdom and crass punning. It is interesting structurally and it is crudely constructed. It is a novel of commitment, keen observation and loving sympathy. In some ways it is a novel of simple faith reminiscent of the Christian novels I was given as Sunday School awards which emphasised salvation through acceptance of a life of no smoking, no drinking, no dancing and certainly no going out with those who did them. But I’m putting this too strongly, for Gary Langford is not as simple minded as to attack modern medicine as the invention of the devil and doctors as the devil’s disciples. But the central thesis is that the protagonist, Mary Stewart, is the victim of our faith that the doctor knows best.

... (read more)Marjorie Barnard, is, of course, a collaborator with Flora Eldershaw in the writing of five novels as well as several other books, under the collective name of M. Barnard Eldershaw. The stories in this collection, most of which were first published in various Australian magazines before they were brought together in 1943, represent her only attempt at solo fiction writing. All of them have some value and interest and among them are some classics, notably the title story which was reprinted in Coast to Coast and has been frequently anthologised since, most recently in Laurie Hergenhan's The Australian Short Story.

... (read more)This is a marvellous book. Bob Browning, an engineer who went to university after his retirement to study history, has produced an analysis of the 1975 constitutional crisis which has no peer in the now bulky literature written about the dismissal of the Whitlam Government. Part detective story, part law treatise, part an essay in historical reconstruction, the book is carefully crafted, sparely written and absorbing throughout. It is going to have a powerful effect on Australian political thinking, because the current generation of Australian politicians will have to come to terms with it, and because for the next ten years at least, university students will be told to work through it from beginning to end.

... (read more)The blurb on the back of Lie of the Land informs us that the collection ‘reeks of Australia’. Apart from being an unfortunate phrase, the offer of a specifically Australian effluvium is too limiting a promise for this wonderful collection of stories. Clanchy’s world is more expansive, and the lie of the land is in no way circumscribed or even. Set in India and Ireland, as well as in different parts of Australia, Clanchy’s stories are vital and restless, and they offer us undisguised accounts of people in conflict with their environment, with others, and with themselves.

... (read more)This book is about a twelve-year-old boy called Ort Flack, into whose life, at a moment of drastic need, bursts none other than God, in the form of a silvery white cloud. The cloud has been there all along, hanging over the house, a personal vision of Ort’s, as mysterious and troubling and comforting to ...

... (read more)Unsettled Areas: Recent South Australian short fiction edited by Andrew Taylor

A reviewer is bound to behave as a different kind of reader from others, especially when dealing with a mixed collection like Unsettled Areas. Other readers can pick and choose, skip the duller bits, and take as long as they like, whereas I’ve read closely every story, at least twice, in the space of two days. Then I’ve let them settle into my imagination for another day or so to see what impressions have lasted, before taking another look. I looked especially hard at the ones I found unsatisfactory, in case my mind had changed. I’ll leave these until later.

... (read more)On the stage or off, Peter Mavromatis is the unswerving centre of these stories. Unswerving as a focus, that is – in himself he swerves all over the place. Who and what is Peter Mavromatis? That’s what he’d like to know. His Cypriot parents and grandmother know who he should be. Sydney-born, he has grown up saddled with Greekness as a birthright and an unpayable debt. Peter Blackaeye: is he ‘Grik’? No, the Greeks at GMH decide, and drive him off the job. Australian? Not to his family, nor to many Australians.

... (read more)Thomas Keneally’s A Family Madness attempts to get the reader in touch with life beyond the headline and the common enough family madness which irrupts the security we call home, sweet home. While each family may be unhappy in its own way, only some hit the screen or the front page, splattering their sorrow onto family breakfasts, lunches, dinners.

... (read more)The Morality of Gentlemen by Amanda Lohrey & This Freedom by John Morrison

This fine first novel by a thirty-six-year-old Tasmanian woman was first published in 1984, but to the best of my knowledge has received only one review. Certainly, ABR missed it, and I would not have read it had it not been entered in the Vance and Nettie Palmer Victorian State Government awards for fiction. Had I been able to persuade my fellow judges of its merit, it would certainly have made the shortlist. Lohrey’s talent as a writer has finally been acknowledged in the latest issue of Scripsi, which prints an extract from the novel she is currently working on, as well as a substantial and thoughtful review by Anne Diamond.

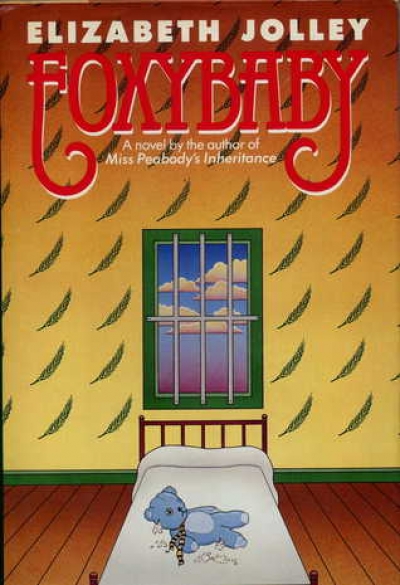

... (read more)A colleague asked if I thought that Elizabeth Jolley’s Foxybaby might have gone ‘over the top’. I assume she meant that the book might be ‘too much’ because the function of its preoccupation with (say) crime and sex, including incest and homosexuality, was not immediately apparent. The question is a reasonable one, but for two reasons I don’t think that her latest novel does go over the top: there is no theme used or technique employed in Foxybaby which has not appeared in Jolley’s writing before; and, ad astra (perhaps per aspera or per ardua), the book represents a logical but highly imaginative development from her most recent work.

... (read more)