Fiction

While the imminent demise of the Australian novel continues to be predicted in the pages of the nation’s broadsheets, a curious thing is happening: two Australian publishing houses are creating new fiction lists. Australian Scholarly Publishing will present its fiction titles under the imprint Thompson Walker, and the University of Western Australia Press has come up with a New Writing series to showcase work from the postgraduate creative writing programmes of Australian universities.

... (read more)The mortality rate for individuals is always one, but for populations it varies from time to time and place to place. London is one of those cities where the mortality rate is high, though not because it has ever been, like the Gold Coast, a city to retire to. For centuries, young people have gone to London seeking riches, celebrity and opportunity. Some, like Dick Whittington, found the streets proverbially paved with gold, but others made their way promptly to the gutter. From the gutter to the grave is but a short step, but not the last one in London during the early days of modern anatomical science, as James Bradley’s new novel illustrates.

... (read more)Disaster has always shadowed the traveller. Today’s adventurers differ from their forebears only in the kinds of calamity they have cause to fear. Arabella Edge’s second novel – like her first, the award-winning The Company (2000) – will have readers thanking their lucky stars that shipwreck, at least, has gone the way of history. As its cover suggests, The God of Spring centres on Théodore Géricault’s masterpiece, The Raft of the Medusa (1819) – its painting, its painter and the real event it depicts.

... (read more)Just how old is John Egan? In a letter to the Guinness Book of Records, he says he is eleven. But the narrative voice of this queer, tormented Irish lad is not that of other boy heroes on the cusp of puberty, the opinionated braggarts whose boasts and fears and primary-coloured perspectives propel their stories. Instead, John’s story lurches from the distractions of the very young to a kind of preternatural knowingness. No wonder John makes everyone around him uneasy. He makes the reader uncomfortable, too.

... (read more)The heroine of Marion Halligan’s latest novel has little time for reviewers. More often than not, she complains, they are ‘patronising ignorant nobodies’ who wouldn’t know a book from a biscuit. I will not hazard a biscuit metaphor, but I will venture a complaint. The Apricot Colonel is as elegantly written as any of Halligan’s novels. It provides the linguistic curios, surprising digressions and insights into storytelling that made Lovers’ Knots (1992), The Fog Garden (2001) and The Point (2003), among others, so exciting. Next to these, The Apricot Colonel is startlingly slight. In Halligan’s best novels, strong story lines tether the witty digressions and thoughtful asides together. In The Apricot Colonel, the plot never seems quite sturdy enough to hold them.

... (read more)The past is not dead. In fact, it’s not even past; it keeps coming back as different novels, and writers do things differently there. Nazi Germany remains history’s prime hothouse from which to procure blooms for fiction’s bouquet. All those darkly perfumed spikes – drama and tragedy intrinsic, memory within recall.

... (read more)The Poet is an unusual book. Dispensing with many of the conventions that underpin most extended works of prose fiction, such as significant characterisation, it presents a central protagonist, Manfred, who is ‘honest’ – as the author repeatedly states. Manfred is also a poet. The novella is written in formal and refined prose, as if the narrative style is designed to reflect Manfred’s obsessional nature and estranged condition: he has never been ‘in love’, is ‘something of a loner’ and is highly anxious.

... (read more)If you can say immediately what you think a novel is ‘about’, then the chances are that it may not be a very good novel. Fiction as a genre gives writers and readers imaginative room to move, to work on a vertical axis of layers of meaning as well as along the horizontal forward movement of narrative development ...

... (read more)How much do you care about sheep? I mean really care about sheep. Because The Ballad of Desmond Kale is up to its woolly neck in them. It’s an unusual and inspired variation on the classic Australian colonial novel of hunters for fortune, for identity and for redemption ...

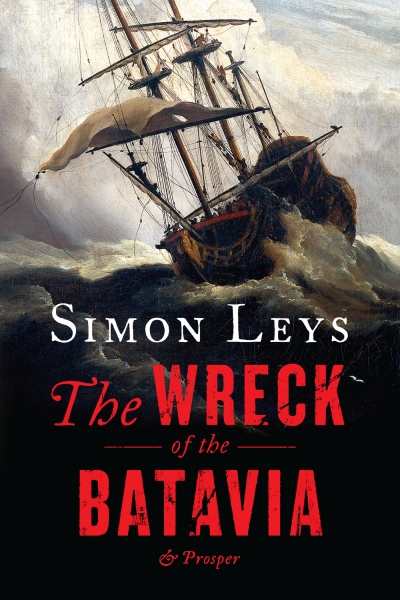

... (read more)In reviewing the first half of Simon Leys’s new book, The Wreck of the Batavia, I’m tempted to regurgitate my review from these pages (ABR, June–July 2002) of Mike Dash’s history of the Batavia shipwreck Batavia’s Graveyard (2002) – especially since Leys also holds that book in high regard, rendering all other histories, his own included ...

... (read more)