Fiction

Longing is the central player in these interlinked short stories, set in India and Australia. Liz Gallois’s characters are questing individuals, resisting the hand that life has dealt them. They negotiate relationships that are fraught with tension – sexual, racial, cultural – all affected by the frailty of their understanding of who they are and what they want.

Western writing that uses India and Indians as counterpoints often veers towards exoticism, but there is a refreshing lack of sentimentality and stereotypes in Gallois’ stories. An individual and confident voice, she often challenges assumptions, sometimes distorting the lens through which the West views ‘India’.

... (read more)Vale Byron Bay by Wayne Grogan & Tuvalu by Andrew O’Connor

These two novels are both strong in their sense of locale, and take their settings as part of the subject, linked to pictures of isolation and barely functioning relationships, and with catastrophe not averted.

... (read more)Life’s not easy when … (fill in the blank according to your main story issue). It is a line that appears frequently on back covers and in press releases for junior fiction. But life is getting a lot easier for parents and teachers of reluctant readers who would far rather race around with a ball than curl up with a book. With the arrival of the sports novel, they can now read about somebody else racing around with a ball – or surfing, swimming, pounding the running track, wrestling, or cycling (the genre covers a wide field). Balls, however, seem to predominate. And problems. Life isn’t easy for publishers without a sports series. Hoping to emulate the success of the ‘Specky Magee’ books written by Felice Arena and Garry Lyon, publishers have been busy throwing authors and sport stars together, one to do the creative business, and the other to add verisimilitude and sporting cred.

... (read more)Careless by Deborah Robertson & Madonna of the Eucalypts by Karen Sparnon

The first thing about Deborah Robertson’s first novel, Careless, that strikes the reader is the way that her prose style cuts like sand. The story of three individuals united by the murder of six children is compelling, but what impresses is Robertson’s love of language, the precision of her sentences, as well as her gentle philosophical imagination and the deeper questions her book seeks to answer.

... (read more)I love travelling overseas. I like the whole flying thing: the taxi ride to the airport wondering what I forgot to pack, the queuing at check-in, the thrill of getting through security. Then there’s the flight itself. The rush of take-off, the first free drink, the little plastic tray with little plastic dishes and plastic knives and forks – just like a picnic in the clouds. Whether the destination is familiar or exotic, I like arriving, too. But one thing I have learned over the years is that no matter where I go, I’ve been there before. Different airport, same old Nick. It must have been much the same two thousand years ago when the Roman poet Horace wrote Caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt – Those who fly across the sea, change the sky but not the me. In the nineteenth century, though, if we are to believe Jem Poster, things were very different.

... (read more)Debra Dean’s novel, The Madonnas of Leningrad, is an exploration of memory and demonstrates how that most mysterious of faculties can both save and fail us. Utilising parallel narratives, Dean tells the story of Marina, a guide at Leningrad’s Hermitage Museum in 1941. As the German army advances, Marina and her colleagues labour to remove and conceal precious works of art. Later, the employees of the Hermitage and their families live in the museum basement, and try to survive the harsh winter with limited provisions.

... (read more)A personal renaissance, with a raison d’ệtre of such significance that it shifts the reverie of the characters in this book into a dimension of former youthfulness and revitalises the possibilities that seem to vanish with age: On a Wing and a Prayer is about friendship, loyalty and respect in the lives of three ordinary people drawn together under extraordinary circumstances in a small country town in central New South Wales. It confounds the adage that once you have reached a certain stage in life there is no further use for you.

... (read more)‘Black Widow’ is the name given to the female Chechen rebels, who were widows of insurgents killed by the Russian army in Chechnya. They went on to serve under Shamil Basayev, leader of the Beslan school siege in September 2004. Sandy McCutcheon has set his latest political thriller two years later, in a story of revenge orchestrated by six female teachers at Beslan, who take on the guise of black widows to turn the tables on the hostage-takers.

... (read more)Sometimes, the middle ground is a good place to be. The Shifting Fog is classy commercial fiction that sits happily in the space between literary fiction and mass-market trash. It might occupy the middle ground, but it’s far from middle of the road. First-time author Kate Morton (recipient of the six-figure sums for deals in eleven countries that publisher Allen & Unwin is happily hyping) has skilfully and intelligently created a novel that is indeed, as the publicity has it, ‘compulsively readable’.

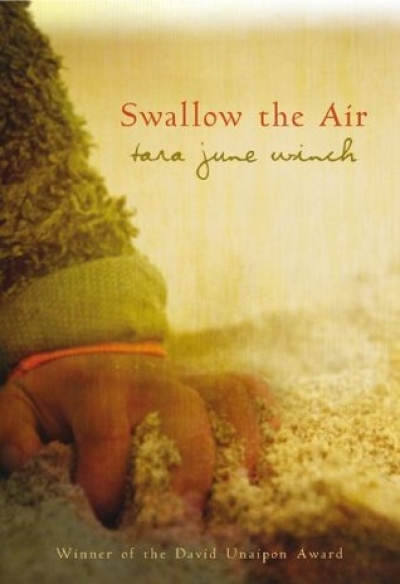

... (read more)Swallow the Air won the 2004 David Unaipon Award for Indigenous Writers. Judging by this slender volume of work, the choice was a judicious one. Thematically, Tara June Winch’s début effort travels along the well-worn path of fiction based on personal experiences, with the protagonist propelling the narrative through a journey of self-discovery. In this respect, Swallow the Air nestles snugly in the semi-autobiographical framework favoured by first novelists, but the sophistication and subtlety of the prose belie Winch’s age; she is twenty-two, but writes with the élan of those much more accomplished. Swallow the Air can either be read as a novel with short chapters or as a series of interlinked short stories.

... (read more)