Fiction

When Tessa wakes up in hospital, she has no idea who she is or how she came to be there. The only clues are the ‘long, thin, striping slashes’ scarring her back. With no way of knowing who or where her family is, Tessa is sent to Cascade Falls College, an exclusive girls’ boarding school on the outskirts of Hobart. She befriends the ‘untouchables’, a group of quirky scholarship studen ...

At the heart of Gail Jones’s Five Bells is a hymn to Kenneth Slessor’s dazzling elegy of the same name, published in 1939.

... (read more)How to review a book that includes, as major characters, Simpson and his donkey, the Dig Tree, and a bus that may or may not be a tram?

... (read more)he Blood Countess is the latest novel by author and media identity Tara Moss. The book promises to be the first in a series about Pandora English, a fashion journalist who socialises with the undead ...

... (read more)The initial premise of John Tesarsch’s first novel sounds like a modern-day reworking of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol as seen through the prism of B-grade Hollywood melodrama ...

... (read more)The Best Australian Stories 2010 edited by Cate Kennedy & New Australian Stories 2 edited by Aviva Tuffield

Amore appropriate moniker for this year’s Black Inc. collection might be ‘Bleak Australian Stories 2010’. Either the editor’s taste runs to the morose or Australian writers need to venture outside and enjoy the sunshine a little more...

... (read more)I Can See My House from Here: UTS Writers’ Anthology 2010 edited by Alice Grundy et al.

The great Russian short story writer Ivan Bunin said that in the process of becoming a writer, ‘one learns not to invent, but to see clearly...

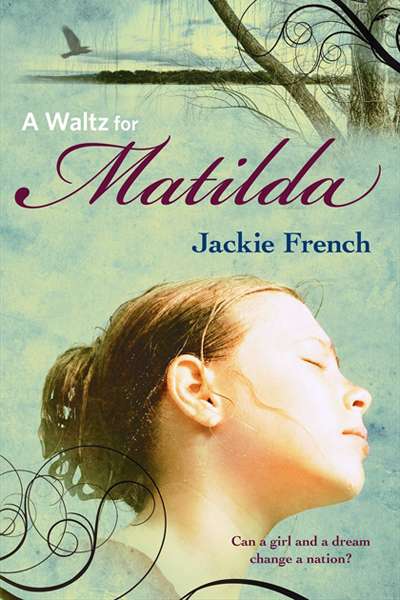

... (read more)Jackie French, a prolific author, is best known for her children’s books, with variations on historical themes clearly something of a specialty. A Waltz for Matilda, which seems to be aimed at a broader market, builds on the premise that the Jolly Swagman of Banjo Paterson’s song is not alone. His twelve-year-old daughter, Matilda, is with him and witne ...

There is much to like in this début Young Adult novel: its straightforward storytelling, distinctive central characters, well-tuned adolescent dialogue, and humorous depiction of first love...

... (read more)