The 2024 Shortlist

ABR is pleased to present the shortlist for the 2024 Peter Porter Poetry Prize, which this year received 1,066 poems from twenty-one countries.

Congratulations to those who reached the shortlist: Judith Nangala Crispin, Natalie Damjanovich-Napoleon, Dan Hogan, Meredi Ortega, and Dženana Vucic. Each of their poems is listed below in alphabetical order by author. For the full longlist, click here.

Poem of the Dead Women

for Marvin Bell

by Judith Nangala Crispin

The dead woman rides a motorcycle, out of Ord River Valley, beyond sand plains, into the serpentine Bungle Bungle Ranges.

And the black sun is over her.

A white dog leans against her back, motorcycle-goggled, his ears flying. He holds himself like a gunslinger,

muscling into oncoming wind. They carve a single-wheeled track into the bulldust of a 360-million-year-old cone-karst plateau.

And as she rides, the unveiled land reveals itself in lucid detail – termite nests and grevilleas. Livistona palm trees stand

like thin gods between rock faces, burnished by dusk.

They pass into the valley of the shadow.

The dead woman has never once said what she intended. ‘Before I knew you,’ she tells the dog, ‘I walked the luminous earth.

But I am in Country now, and the Country is in me.’

The dog has no opinion on this, or any other matter.

The motorcycle bears them north over monsoonal savannahs, into deeper valleys studded with orchids and ferns,

into the shelter of steep red cliffs.

The dead woman introduces herself to the Country she rides through.

She surrenders her name to silverleaf bloodwoods, acacias and rough leaf range gums.

And she tells them how she crossed the desert thirty-six times alive – and once dead.

How she stockpiled electrolytes and anti-venom, water bladders, multi-tools and rope.

How the dog survived a king brown bite and the hungry gaze of eagles.

How she was run over in a remote desert town by a single mum, shouting at the kids in a gigantic SUV.

Grey nomads do not notice the dead woman passing.

They’re cooking sausages on Webers outside their camping trailers or adjusting solar panels for satellite TV.

She does not stop at the Ranger’s office for permits, kayak hire or a personal locator beacon.

At the bus bay, disembarking hikers upload Instagram selfies under banded domes, lifting 300 meters above the grasslands like titanic beehives.

And the tour guide explains how their tangerine stripes are iron and manganese, but the grey ones are cyanobacteria –

ancient organisms living in a surface-deep layer of clay.

They have colonised multitudes of domes, holding them in their forms over millions of years.

The slightest touch could break their living skin, crumbling these sandstone minarets back into dust.

The dead woman introduces herself to the cyanobacteria, to the iron and manganese.

She claims no ownership of this or any other land.

She is tolerated like seeds of subtropical trees, carried inland on the feet of migrating birds, and dropped where they will not grow.

Country knows this but is too polite to say so.

The dead woman’s panniers carry journals filled with coloured pencil drawings – maps and pressed plants. There are poems.

There are notes on the movements of honeyeaters, wood swallows and white-quilled rock pigeons.

The journals have many missing pages – torn out, loosed into wind like pollen or white nocturnal moths.

The dead woman knows some stories can’t be spoken.

Over the still world, Gouldian finches turn in kaleidoscopic arcs. Their bone-curved wings are written

with the mystery of seeds – yinirnti and mulga. Seeds of the ground.

Sky seed.

The dog and his dead companion pass in chasms where waterfalls cascade down sheer rock,

between fig vines and moss. Snappy gums regard themselves in the surface of mirrored pools.

The dog shouts at lizards skittering over shiny river stones.

Dunnarts and planigales in the hollows.

A nailtail wallaby crashes through the bush, where cliffs cycle through their colour spectra at dusk, gold to purple,

and a baritone wind explores reefs of an inland sea.

The dead woman has finally understood that this is not a dress rehearsal.

She dismisses inner whispers that it’s already too late, that her efforts can wait for some future life.

She sees who it is that whispers.

She is no longer an animal with an angel inside her chest –

the animal rejecting the angel, the angel always looking for an escape.

The dead woman holds her arms up into the sky. ‘How pale this sky is,’ she says to no one in particular. ‘How pale.’

She slows the motorcycle where palm trees drop into rockholes, and the cliffs glow as if lit from the inside.

She chooses a campsite.

Looking down from a tourist helicopter, you’d see an elliptical plateau, 7.5 kilometres wide, surrounded by domes.

This is the remnant of Picaninny Crater, the seventh gate, where the star fell down.

The dog clambers over boulders tossed by the meteorite. He is a whiteness on incarnadine stone.

All the creeks and pools are silver on night’s border. Ursa Minor, Centaurus and Crux are sparks

on the watered roots of trees. She hears palms conversing in their slow vegetal language.

Crows and their dark spies are signalling across the gorge. Their cries sound like machineguns or breaking glass.

And the dead woman answers, ‘My crow. My black-breasted buzzard.’

Her hair is dark and bright in the sky. Her rivers flow from these ranges to the sea, returning again

to the mountains in deep subterranean veins. She is a circulatory system, a new topography of light.

The dead woman is not looking for a door. She will not get drunk and join the Scientologists, won’t search

for answers in grimoires, tarot cards or wormholes, or in boxing matches, or late-night confessions with online language bots.

She has already written her history in blood and milk and venom.

She perches above the rockholes like a kingfisher, waiting for the flash of something silver in the deep.

There are mountains and rivers beneath the dead woman’s skin.

Her breath drifts over them.

Judith Nangala Crispin is a poet and visual artist of Indigenous and mixed descent, living on unceded Yuin Country on the NSW Southern Tablelands. She has published two collections of poetry, and her verse novel will be released this year. Judith won the 2020 Blake prize for poetry and has been shortlisted for various other prizes. She has been commissioned by The National Gallery of Australia, The National Museum of Australia, Musica Viva, and Red Room Poetry. Judith has a PhD in music and has just completed a Doctor of Arts in Poetry. Her work has appeared in numerous Australian and international journals and anthologies over the past twenty years. In 2024, a poem Judith wrote about her dog will be deposited on the Moon, by NASAs Polaros mission, as part of the Lunar Codex.

Judith Nangala Crispin is a poet and visual artist of Indigenous and mixed descent, living on unceded Yuin Country on the NSW Southern Tablelands. She has published two collections of poetry, and her verse novel will be released this year. Judith won the 2020 Blake prize for poetry and has been shortlisted for various other prizes. She has been commissioned by The National Gallery of Australia, The National Museum of Australia, Musica Viva, and Red Room Poetry. Judith has a PhD in music and has just completed a Doctor of Arts in Poetry. Her work has appeared in numerous Australian and international journals and anthologies over the past twenty years. In 2024, a poem Judith wrote about her dog will be deposited on the Moon, by NASAs Polaros mission, as part of the Lunar Codex.

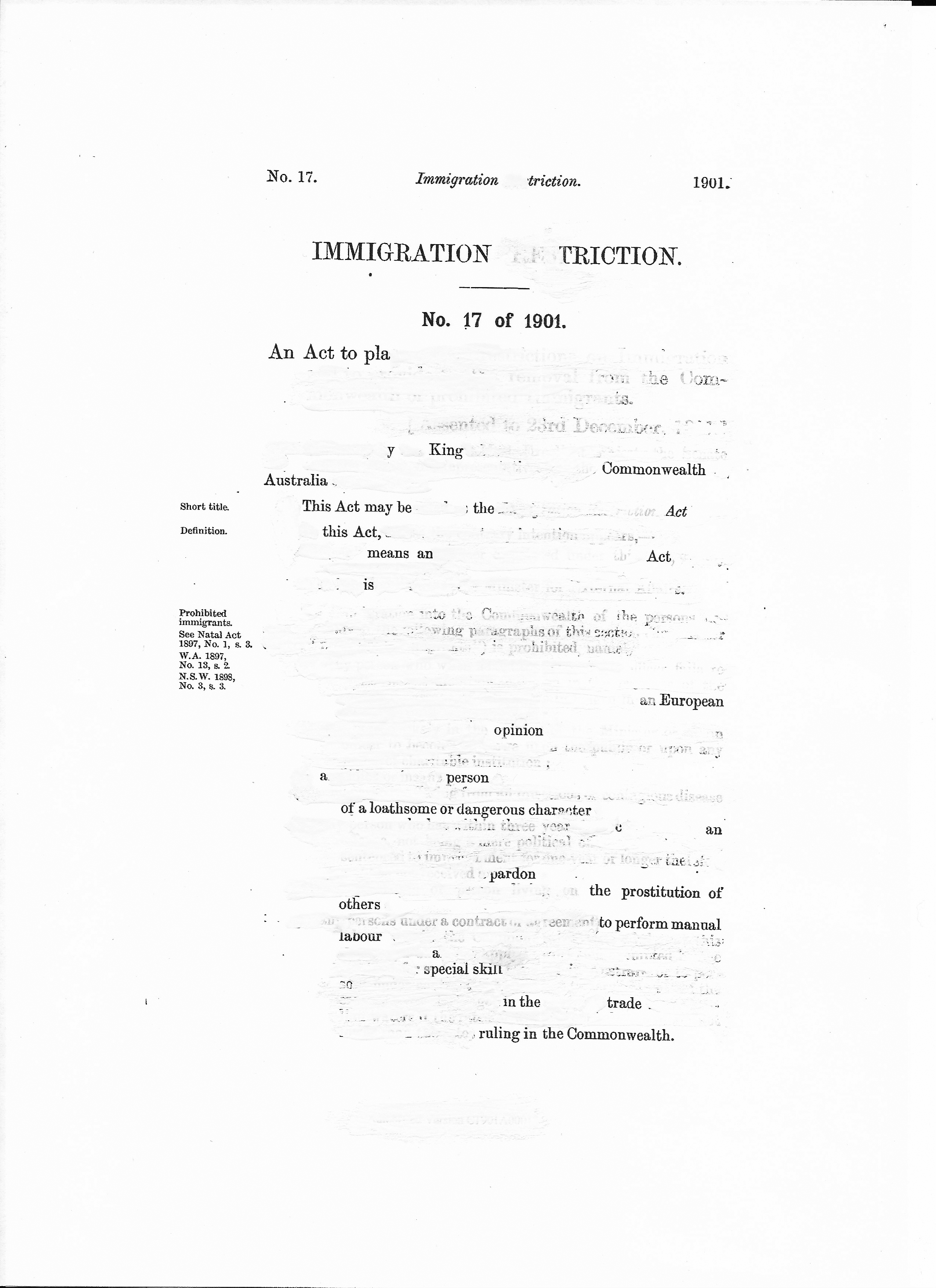

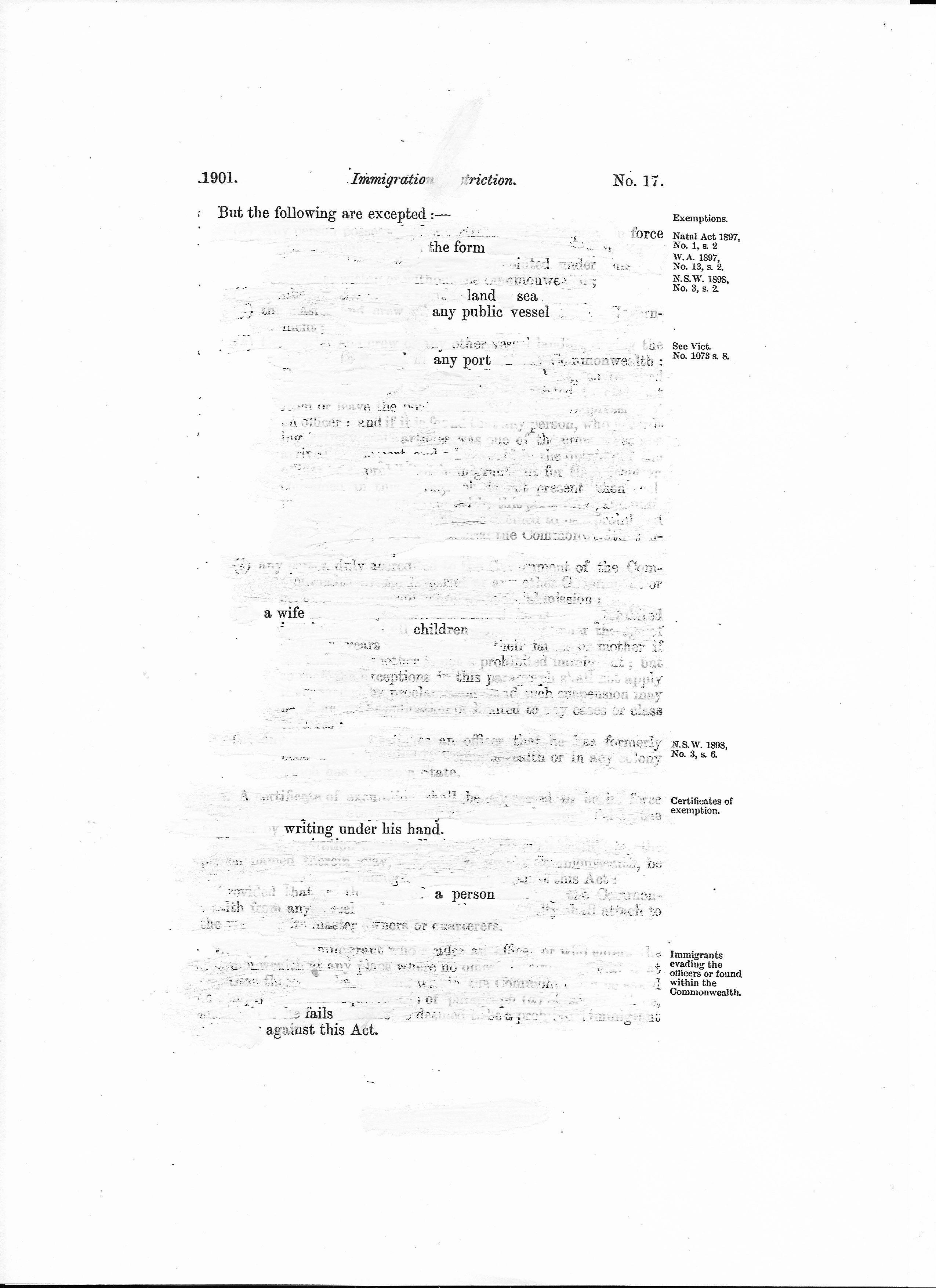

Immigration Triction

by Natalie Damjanovich-Napoleon

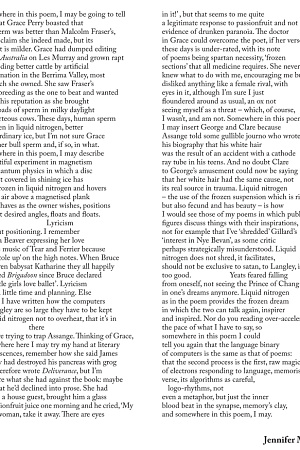

This is an erasure poem created by hand, using white out to remove portions of the source text.

Reference: Immigration Restriction Act 1901. (1901, Dec 23). Federal Register of Legislation.

https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C1901A00017 (Commonly known as the White Australia Policy).

Natalie Damjanovich-Napoleon is a writer, songwriter, and educator who was raised on a farm by her Croatian-immigrant parents. Her poetry and creative non-fiction have appeared in Meanjin, Cordite, The Found Poetry Review, Westerly, Australian Poetry Journal and Writer’s Digest (US). Natalie’s work has been widely anthologised in both the United States and Australia. She helped run the Voicebox poetry reading series in Fremantle. She has won the Bruce Dawe National Poetry Prize (2018) and the KSP Poetry Prize (2019). Her début poetry collection, First Blood, was released in 2019 (Ginninderra Press). Her second poetry book, If There Is a Butterfly That Drinks Tears, on motherhood in the wake of the Trump presidency, was released in 2023 by Life Before Man/Gazebo Books. Currently, she is completing a PhD in Creative Writing through Edith Cowan University, where she wrote the poetry collection The Commonwealth of Amnesia’, a series of erasure poems on xenophobia, war paranoia, and the forgotten histories of Croatian people in Australia.

Natalie Damjanovich-Napoleon is a writer, songwriter, and educator who was raised on a farm by her Croatian-immigrant parents. Her poetry and creative non-fiction have appeared in Meanjin, Cordite, The Found Poetry Review, Westerly, Australian Poetry Journal and Writer’s Digest (US). Natalie’s work has been widely anthologised in both the United States and Australia. She helped run the Voicebox poetry reading series in Fremantle. She has won the Bruce Dawe National Poetry Prize (2018) and the KSP Poetry Prize (2019). Her début poetry collection, First Blood, was released in 2019 (Ginninderra Press). Her second poetry book, If There Is a Butterfly That Drinks Tears, on motherhood in the wake of the Trump presidency, was released in 2023 by Life Before Man/Gazebo Books. Currently, she is completing a PhD in Creative Writing through Edith Cowan University, where she wrote the poetry collection The Commonwealth of Amnesia’, a series of erasure poems on xenophobia, war paranoia, and the forgotten histories of Croatian people in Australia.

Workarounds

by Dan Hogan

We completed tasks while your computer

was nonplussed. Never under any circumstances

outgather the USB cables as they are known

to the fossil record. Is anyone using this

rubric? A strongly worded mop bides here.

An epoch before us, an equivalent energy.

The moral to the story is a horny talkathon.

Posting generally is a captive curation. A scared

village buys now, pays later. Bags odourous

gains. Inside everywhere is time. Skeletons

made of other skeletons undergo workarounds.

Withdraw a like. Troubleshoot the jig if it starts

to look like your brain on internet, dollied blunt. Histories

of conspiratorial durdum are loading. Uh oh. A tiptoe

extravaganza engrooves serious laughlines. Deceives

blessedly. The droplets collecting on necks are owed

to the multipurpose fog. Order an adapter while

buff. Moths single out appliances to dent. Great

magistrates are coming your way. The depth

of a field is a streaming service. Who humours

the non-electric fence? Is it you who licks it clean?

Resemble the viral. Property the essential. Outdo

outcomes as opposed to going home on time. Plumb

the blameless. Countdown to glitches. Spondulix

when? Depolished chitchat, gutbucket sunrise. Lunch

on the old roof fizzles out. You can fail the creek.

But the bike. The bike is in the creek. Bestow

little quizzes. Then the second moment of area (clue:

see toward a federation of etcetera crises). Surface

a length of singsong worseness, refranchise exquisite

doldrums. Swanky exits expect better. It is time for

your next marathonic ache. Enrapture well, dear salad

and lots of mozzies. An existential kneecapping.

Real windsock hours. Unhallowed visits from

tricky miniatures clog the month. Eventually,

prescriptions. Entablature. Maximum research.

Netlike greenth. Bigheadedly nod if you want

to defragment. Reevaluate persuasions over mild

interludes. Up the revelry. Roster on fleetingness.

Consult moments. Misallocate enthusiasm for

stakeholders. Dream-eating surucucus warm the

pit. Indispensable attunements are down the hall.

Minimalism is for jerk apologists. According to

resorts the cement world is everything a unit of

productivity could want. Put it this way: the forest

wasn’t November. Allegedly joyless. Heart an

an infographic. Repot survival news. Favourite

an unopened secret.

Dan Hogan (they/them) is a writer from San Remo, NSW (Awabakal and Darkinjung Country). They currently live and work on Dharug and Gadigal Country (Sydney). Dan’s debut book of poetry, Secret Third Thing (Cordite, 2023), won the Five Islands Poetry Prize. Dan’s work has been recognised by the Val Vallis Award, the Judith Wright Poetry Prize, and the XYZ Prize, among others. In their spare time, Dan runs small DIY publisher Subbed In. More of their work can be found at: 2dan2hogan.com.

Dan Hogan (they/them) is a writer from San Remo, NSW (Awabakal and Darkinjung Country). They currently live and work on Dharug and Gadigal Country (Sydney). Dan’s debut book of poetry, Secret Third Thing (Cordite, 2023), won the Five Islands Poetry Prize. Dan’s work has been recognised by the Val Vallis Award, the Judith Wright Poetry Prize, and the XYZ Prize, among others. In their spare time, Dan runs small DIY publisher Subbed In. More of their work can be found at: 2dan2hogan.com.

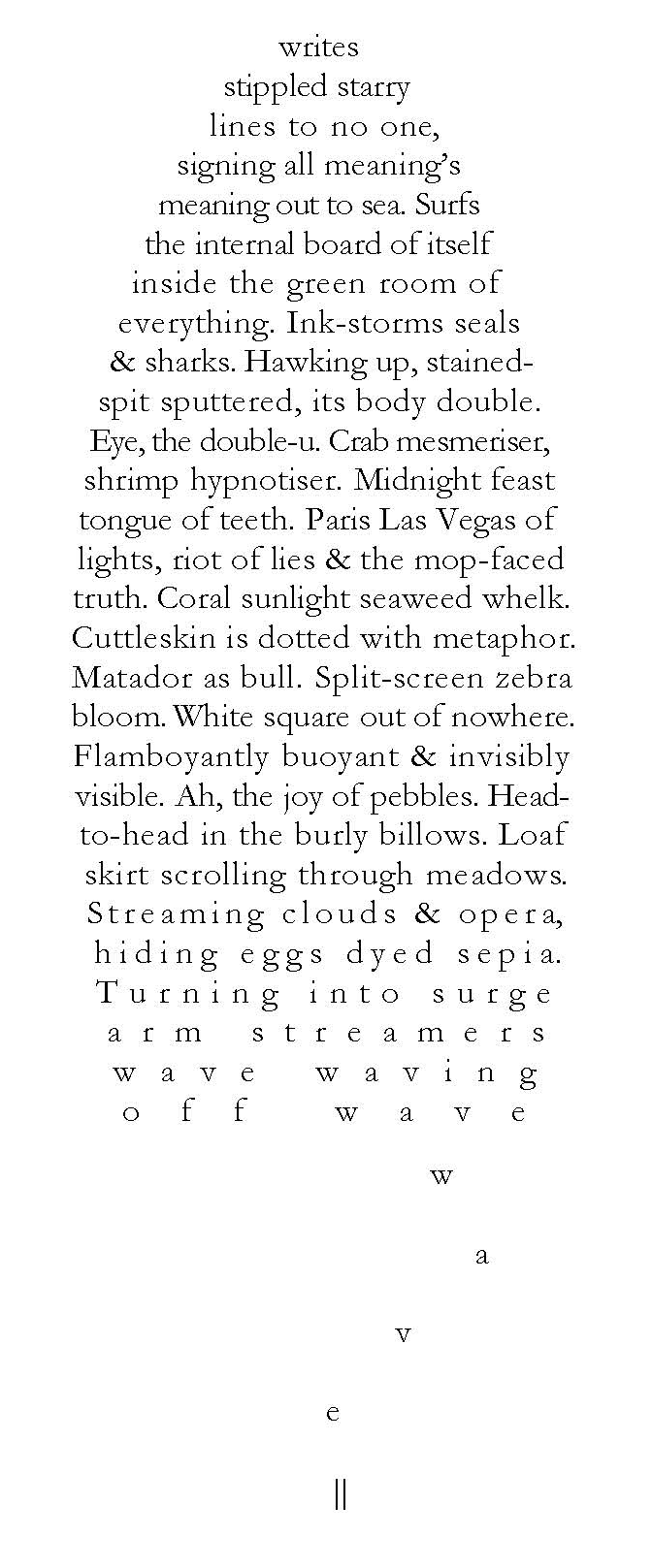

Cuttle

by Meredi Ortega

Meredi Ortega is from Western Australia and now lives in Scotland. Her poems have appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, The Poetry Review, Meanjin, The Best Australian Science Writing 2023, and Scientific American. She contributed to the deep mapping anthology Four Rivers, Deep Maps (UWAP, 2022).

Meredi Ortega is from Western Australia and now lives in Scotland. Her poems have appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, The Poetry Review, Meanjin, The Best Australian Science Writing 2023, and Scientific American. She contributed to the deep mapping anthology Four Rivers, Deep Maps (UWAP, 2022).

Blagaj, Mostar

by Dženana Vucic

The sky was crumbling; so full of sun it burnt at the edges and hit

the cracked earth of my aunt’s garden in waves. It was a summer

dense with figs splitting flesh on the tree. Pomegranates had burst

open against the concrete drive, spilling their insides. On the steps:

red chillis drying in neat rows on a white keranje she had made

herself. Bundles of herbs. Thyme for čaj and sage to cure a sore

throat. A tidy line of orthopaedic shoes, his and hers, a pair on each

step. Months before the lilac had been in bloom, the forsythia. We

had walked around the garden breathing them in, my aunt pointing

to her silver beet, trellised beans, zucchini ripening against the soil.

Neat rows of carrot and potato. The apple and cherry trees had just

shrugged off their blossoms; there had been elderflower juice.

Today my aunt has cooked with a bountiful harvest: spirals of

cheese and spinach rolled in pastry so thin you can see the new

moon through it; quarter chunks of tomato and cucumber dressed in

oil; spring onions in yoghurt; a loaf of fresh yellow bread. There’s

a watermelon cooling in the river for dessert. Beside it, too: plums,

persimmons, ripe fruit scattered across the ground to be fetched after

the meal. Inside: baked apples stuffed with walnuts and fried dough

soaked in sugar. We are waiting for my uncle, gone fishing. If he’s lucky,

my aunt will fry a river trout or two – lightly, with a little flour, a little

salt. Skin on and crispy. My uncle will make his same jokes, needling

my kind aunt with her plum-soft heart. Take this one away with you,

he’ll tell me. She’s no good – just look at all this food she hasn’t made.

In the war, almost my lifetime ago, my aunt took her children in her

arms and crossed the barebone mountains to our house. Hers had

become a waiting grave. My uncle arrived every three weeks, a two-day

hike each way. Limping, he wore a trail into the stone earth to find her,

to sit in her weather for three days. Alhamdulillah my aunt said. Well,

where’ve you been? my uncle replied. Then he was gone. Then, as now,

my aunt filled our plates: palačinke and uštipci when there was flour;

pickled cabbage; stewed pears; bean soup stretched for weeks. My mother

was a nurse in the village and in the evening the sisters sat together,

drinking coffee when there was some, cracking walnuts between their

palms, waiting for the men to come home. Take this one with you,

my uncle jokes. But he would follow. He knows the way.

Above us the old fort looms its jagged teeth across the mountain.

After coffee we will walk to its base picking blackberries and water

mint along the way, then stand on the karstic lip overlooking history:

the tekija where old Sufi clerics chanted Dhikr and where the mountain

splits itself open to send the green Buna swirling past the house. They

say that after his death, a great cleric had his body buried in seven

tombs across the Balkans – choosing always small towns, out of the

way places, so that as pilgrims made their journeys to honour him,

they would spread the word that there are as many paths to God as

there are breaths in a human body. My aunt knows all the names of

Allah, though like all our people she says sabur, forbearance, most.

My uncle is not a religious man, though he has been a pilgrim.

Dženana Vucic is a Bosnian-Australian writer, poet and critic currently based in Berlin. Her writing has appeared in Sydney Review of Books, Overland, Meanjin, Australian Poetry Journal, Australian Multilingual Writing Project, and others. She is currently working on her first book and tweets at @dzenanabanana.

Dženana Vucic is a Bosnian-Australian writer, poet and critic currently based in Berlin. Her writing has appeared in Sydney Review of Books, Overland, Meanjin, Australian Poetry Journal, Australian Multilingual Writing Project, and others. She is currently working on her first book and tweets at @dzenanabanana.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.