Arts

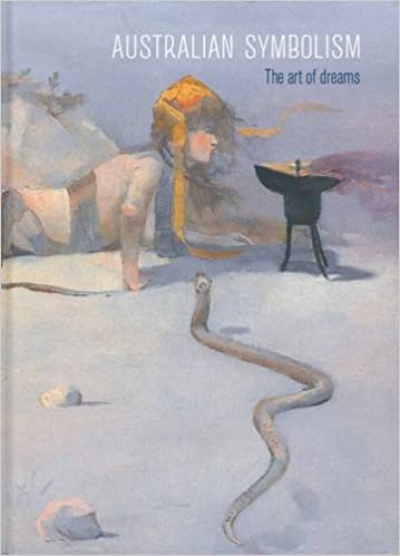

Australian Symbolism by Denise Mimmocchi & Van Gogh to Kandinsky by Richard Thomson, Frances Fowle, and Rodolphe Rapetti

by Jane Clark •

All Our Relations: 18th Biennale of Sydney 2012 by Catherine de Zegher and Gerald McMaster

by Felicity Fenner •

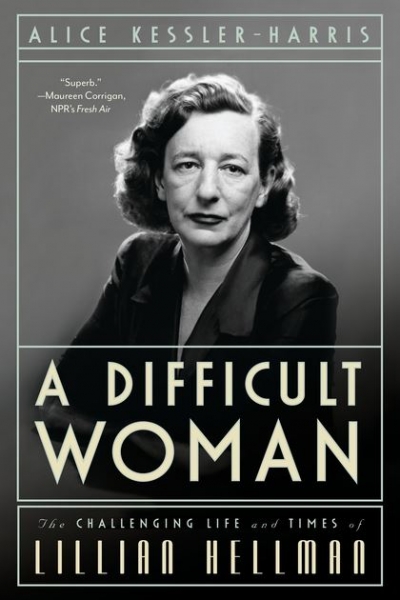

A Difficult Woman: The Challenging Life and Times of Lillian Hellman by Alice Kessler-Harris

by Desley Deacon •

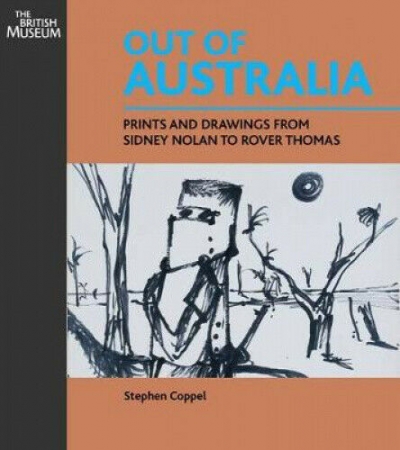

Out of Australia: Prints and Drawings from Sidney Nolan to Rover Thomas by Stephen Coppel

by Angus Trumble •

Michael O’Connell: The Lost Modernist by Harriet Edquist

by Morag Fraser •

Unexpected Pleasures: The Art and Design of Contemporary Jewellery by Susan Cohn

by Christopher Menz •

Australian Art and Artists in London, 1950–1965: An Antipodean Summer by Simon Pierse

by Sarah Scott •

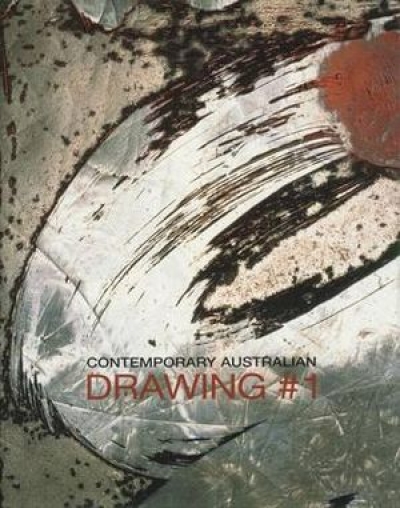

Contemporary Australian Drawing #1 by Janet McKenzie, with Irene Barberis and Christopher Heathcote

by Justin Clemens •