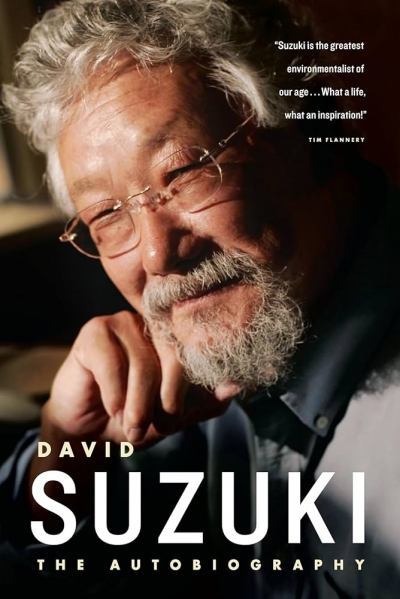

David Suzuki is perhaps the best-known scientist living today. After developing an international reputation as a leading geneticist, he moved into science broadcasting and environmental activism. Why did he do this, and how did he become so successful? Now aged seventy, Suzuki explores these questions in his latest book, David Suzuki:The Autobiography. Suzuki’s previous auto-biographical work, now out of print, was aptly titled Metamorphosis: Stages in a Life (1986). Evolving from a collection of essays, it also charted his transformation from laboratory scientist to public educator of science and environmentalist. However, much has happened in the intervening twenty years. The new book mostly focuses on his environmental work in Canada and the Amazon, leading to the establishment of the David Suzuki Foundation in 1991, and his subsequent involvement in the Rio Earth Summit (1992) and the Kyoto Agreement on climate change (1997). In his preface, Suzuki writes that his story has been ‘created by selectively dredging up bits and pieces from the detritus of seventy years of life’. It is neither a story of the inner machinations of science nor the intrigues of a public personality in the media. Rather, Suzuki takes the position of an ‘elder’ in society, with the hope that his reflections on life may stir the reader to reconsider his or her own life.

...

(read more)