Memoir

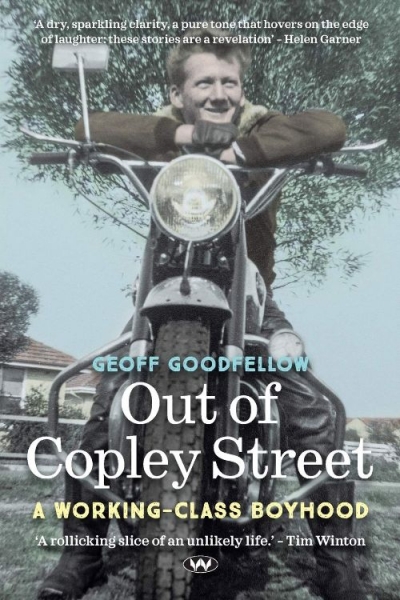

Out of Copley Street: A working-class boyhood by Geoff Goodfellow

by Jay Daniel Thompson •

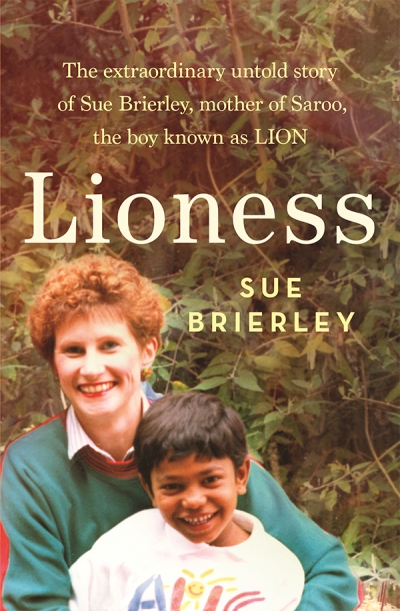

Lioness: The extraordinary untold story of Sue Brierley, mother of Saroo, the boy known as Lion by Sue Brierley

by Margaret Robson Kett •

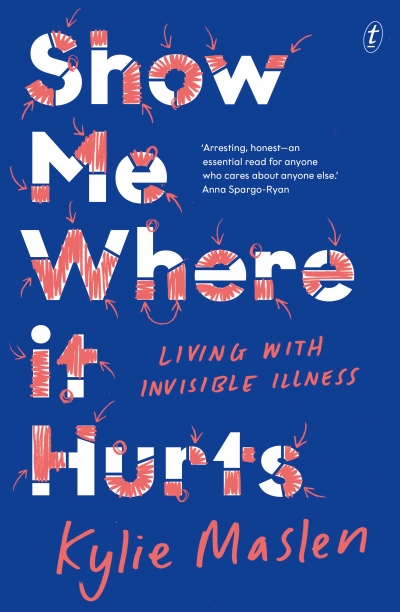

Show Me Where It Hurts: Living with invisible illness by Kylie Maslen

by Kate Crowcroft •

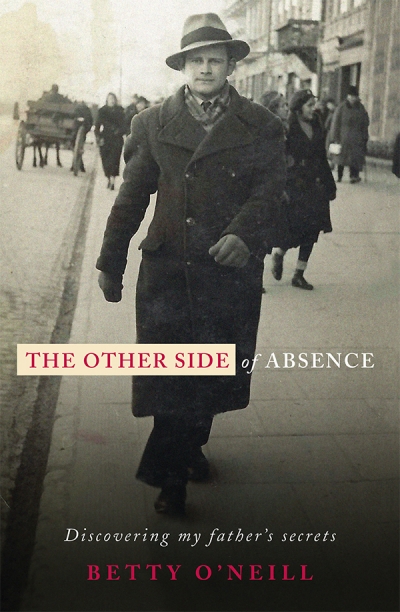

The Other Side of Absence: Discovering my father’s secrets by Betty O’Neill

by Iva Glisic •

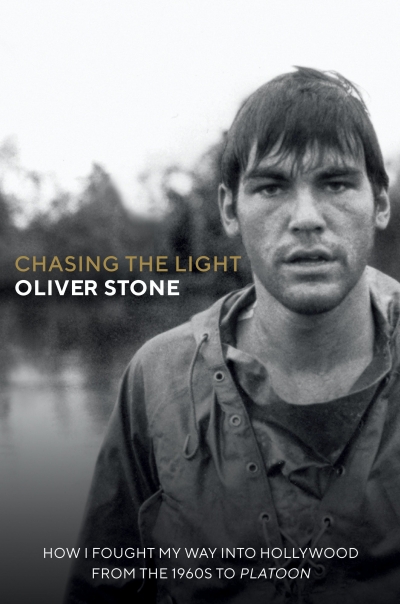

Chasing the Light: How I fought my way into Hollywood: From the 1960s to Platoon by Oliver Stone

by Aaron Nyerges •

The Time of Our Lives: Growing older well by Robert Dessaix

by Francesca Sasnaitis •