Children's and Young Adult Books

Maya Linden

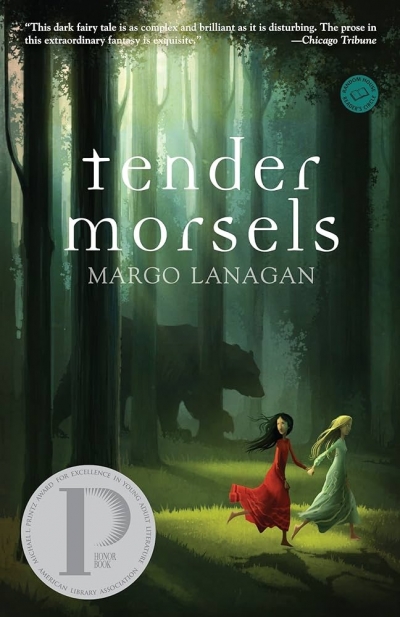

Amid the proliferation of fiction inspired by supernatural themes, it is refreshing to find several débuts concerned with the more mundane – yet perhaps more pertinent – quests of adolescence. Tohby Riddle’s The Lucky Ones (Penguin) explores a period of change in the life of Tom, an aspiring artist, as he negotiates the purgatory between high school and adulthood. Told in a conversational voice, punctuated with poetic observation, it is a meditation on ‘the faint sadness that seems to underpin all things wonderful’.

... (read more)Lost! by Stephanie Owen Reeder & 60 Classic Australian Poems edited by Christopher Cheng

Learning about the world is one of the great fruits of reading. It can be as much fun as solving a puzzle, provided the information is presented to invite questioning and interpretation. These five attractively produced, accessible books are designed to appeal to their intended audiences, but how well do they avoid the over-simplification that is an inherent danger in tailoring ‘facts’ to the needs and interests of inexperienced readers?

... (read more)