The Marriage of Figaro

Sydney has had its coldest July in decades, and the rain it raineth every day, but this did not deter operagoers from savouring two further offerings in the winter season: a fine revival of what must rate as one of Opera Australia’s best Mozart offerings, and a new production of Antonín Dvořák’s melodious fairy tale.

ABR Arts last saw David McVicar’s production of Le Nozze di Figaro in 2015. This was in Melbourne, soon after the Sydney première, which Michael Halliwell reviewed. Figaro followed an equally good Don Giovanni from McVicar in 2014. The ubiquitous Scottish director completed the Mozart-Da Ponte trilogy in 2016 with Così fan tutte.

These three immortal operas, especially in such expert and sympathetic hands, should not be absent long from a major company’s repertoire. Commercially they may even rival such curiosities as Sunset Boulevard. Acting CEO Simon Militano reminds us in the program that Figaro ‘launched the company’s journey’ in Adelaide in 1956. To paraphrase Melba, if you want to educate new opera audiences, give ’em Mozart. Striking on this occasion was the rapport between the musicians and the audience (warmly alert to comic nuance). It was like being part of a knowing Shakespeare audience. Perhaps there was an element of relief in the Joan Sutherland Theatre that, after volatile times and uneven seasons, the company was returning to its roots.

McVicar’s production – with inspired sets and costumes by Jenny Tiramini – looks exceptionally good on the small Sydney stage. There is surprising amplitude, dramatic flexibility, skilful blocking – all needed in such a dark farce, rightly subtitled La Folle Journée. Revival director Andy Morton deploys the large cast with admirable fluency and psychological focus.

Always an event, any production of Figaro affords a good excuse to revisit, however briefly, the gestation of Mozart’s seventeenth opera, which had its première in Vienna on 1 May 1786. Mozart had suggested Beaumarchais’s 1778 play Le Mariage de Figaro – the most popular of the three plays in the Almaviva Saga – to Lorenzo da Ponte. The opera emerged quickly, though not in the six weeks of legend. Da Ponte’s record as a librettist had been patchy until then, but his Figaro is considered a masterpiece. Inevitably, it is much shorter than Beaumarchais’s five-act play, and Da Ponte was forced to expunge passages of revolutionary fervour to appease Emperor Joseph II, who had banned the play. Da Ponte assured him that he had removed anything that might ‘offend good taste or public decency’. Still, Mozart set out to inject more seriousness into comic opera, and this he did incomparably.

Auspiciously, the current season boasts several company débuts, or near débuts.

In the title role, Michael Sumuel, from Texas, was a memorable Figaro, engaging and nimble from the opening scene, when Figaro measures up the room in anticipation of the Count’s wedding gift, a splendid bed, only to be disabused by Susanna about their master’s true intentions. Sumuel sang well all night and was at his best in Figaro’s great, embittered recitative and aria in Act Four, when Figaro laments having to learn ‘the foolish art of being a husband’.

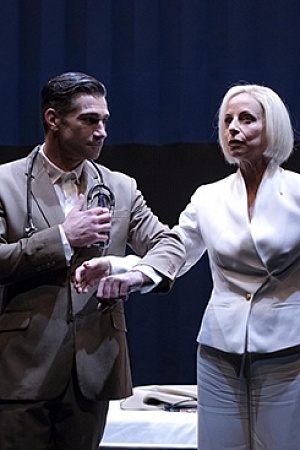

Kiandra Howard as Countess, Sioban Stagg as Susanna and Gordon Bintner as Count (photograph by Keith Saunders)

Kiandra Howard as Countess, Sioban Stagg as Susanna and Gordon Bintner as Count (photograph by Keith Saunders)

Mozart gives the Countess, so scurvily betrayed by her repellent husband, some of the loveliest music he ever wrote, but she can be a stultifying presence – not unlike Donna Anna, of whom Maria Callas said: ‘I am not belittling her music, but really that woman is a crushing bore.’ Kiandra Howarth, in only her second role for Opera Australia, brought something different to the part – more pert and alert than most Countesses, sisterly too in her connivance with Susanna, and always humorous in her exchanges with the gauchely infatuated Cherubino. The Countess’s evening begins with the exposed aria ‘Porgi amor’, which opens Act Two. Howarth negotiated it beautifully, with a rich tone and emotional depth. ‘Dove sono’, from Act Three, was even better. Let’s hope we hear this young soprano in other Mozart roles.

Rather belatedly, this production marks Siobhan Stagg’s début with Opera Australia, though the Berlin-based Australian soprano has in recent years been a regular visitor with other ensembles and orchestras. This is not Stagg’s first Susanna; she has sung it at Covent Garden and with the Komische Oper Berlin. Stagg brought her customary beauty of tone and phrasing to the role; her ornamentations were impeccable. ‘Deh vieni, non tardar’, Susanna’s Act Four aria, was sung with great feeling and delicacy.

Some of the best music came in Act Three, with the sextet ‘Riconosci in quest’amplesso’, which was said to be Mozart’s favourite piece in the entire opera. This masterly ensemble was followed by the serene duet ‘Che soave zeffiretto’, when the Countess and Susanna compose a letter that will expose the rapacious Count – bel canto at its finest, exquisitely sung by Howarth and Stagg.

As with Der Ring des Nibelungen, casting Le Nozze di Figaro is never easy, and this production had a couple of disappointments.

Canadian Gordon Bintner, another debutant, is the Count. Tall, youthful, mobile, he looks the part and brought requisite menace and haughtiness to the role, but he was not in good voice, and some of his notes bordered on the irregular, especially his sudden plea for forgiveness at the end (‘Contessa, perdono’), which should be one of the most affecting moments in the opera. Howarth rescued the situation in refulgent voice, as the magnanimous Countess forgives him: ‘I am kinder / I will say Yes.’

Emily Edmonds, in her second role for the company, is not a natural Cherubino either dramatically or vocally.

Dominica Matthews was in good voice and lively comic form as Figaro’s avenging fiancée and ultimate madre. Like many a Marcellina before her, she lost her Act Four aria, ‘Il capro a la capretta’. There were other cuts, not unusual. These included Don Basilio’s (Virgilio Marino) ‘In quegli anni’. Richard Anderson was a perfect comic foil as Dr Bartolo. Celeste Lazarenko, who has sung Susanna for the company as well as Pamina and Donna Anna, impressed as Barbarina.

Italian Matteo Dal Maso – another company débutant – tore into the famous Overture and maintained an impressive bond with principals and chorus alike throughout the long evening. The playing was consistently good, with highlights from woodwind, brass, and fortepiano continuo.

Here is a futile aside: might Mozart, had he lived longer, have been drawn to the third play in Beaumarchais’s trilogy? This was the post-revolutionary La mère coupable (The Guilty Mother, 1796), which was one of Napoleon’s favourite plays. By now the Almavivas are plain ‘Monsieur et Madame Almaviva’. They have sold their estate in Seville. Then the old Count learns that one of their sons is the child of the Countess and Cerubino: the Countess is revealed as the eponymous ‘guilty mother’. (At times, following the Mozart-Da Ponte operas is like trying to keep up with an Iris Murdoch plot, with all their impulsive intricacies of love.)

In his comprehensive review, Michael Halliwell welcomed the new production of Antonín Dvořák’s Rusalka – only the second time it has been done by the national company. I heard it midway through the run, on August 1.

Always evident is the sheer opulence of Dvořák’s supremely assured orchestration, with its beguiling languorousness. When Rusalka was first performed in the United States (in 1975, seventy-five years after its première), Andrew Porter wrote: ‘It is an opera not so much of character as of atmosphere, and the effect is that of a symphonic poem given theatrical shape.’ Charmed but disbelieving, we sink into this mellifluous opera as into an endless stretch of Wagner, of whom Dvořák was an admirer.

The opera demands five adventurous singer-actors with expansive voices, and none disappointed. Gerhard Schneider, making his début with Opera Australia, has a relatively light voice for Dvořák’s Prince (Schneider seems like a natural Ferrando or Don Ottavio), but he has sung it often elsewhere and he did so here with considerable elegance and flair. Ashlyn Timms, brilliantly costumed, was an imposing Jezibaba, at her best in the hilarious Abracadabra aria (‘Čury mury fuk’).

But we go to Rusalka for the water nymph, and there was special interest on this occasion, which marks Nicole Car’s début in a role which she will soon sing in her principal houses: Paris and Vienna. Car, with four performances under her belt, was in sensational voice. Since 2014 ABR Arts has reported on many notable performances from the young Australian soprano – Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni, Tatyana in Eugene Onegin, and Margeurite in Faust spring to mind – and her singing in OA’s recent Verdi Gala in Melbourne revealed sumptuous new dimensions to the voice, but this was probably her best performance to date. Over the years I have heard some mighty performances in this house, going back to Joan Sutherland’s Violetta and Lucia in the late 1970s, but nothing has surpassed Car’s performance as Rusalka.

The season ends on August 11; there are three more performances (though I understand the matinee on August 9 has sold out). Seize any opportunity to hear Nicole Car in this glorious form while you can.

The Marriage Figaro (Opera Australia) continues at the Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House until 27 August 2025. Performance attended: July 31. Rusalka (Opera Australia) continues there until August 11. Performance attended: August 1.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.