Siegfried (★★★ ½) and Götterdämmerung (★★★★★)

Of all the major operas, Siegfried had the most curious gestation. After completing Act II in 1857, Wagner put it aside for twelve years, ‘as if weary of Siegfried’s progress: this improbable hero’s search for love, fulfilment, individuation’, as I suggested in my review of Opera Australia’s production in 2016. During those years – in a matchless digression – Wagner wrote Tristan und Isolde (1865) and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1868).

Wagner had planned to write a single opera, not four of them. It was to be Siegfrieds Tod (Siegfried’s Death). Wotan and the gods were not part of this conception. Then Wagner realised that Siegfried – callow, ebullient, unworldly – had to confront his burdened, dangerous grandfather, the killer of Siegfried’s father, Siegmund.

The new production opens with Andrew Bailey’s busiest set to date. The cave that Siegfried shares with Mime, brother of Alberich, has become a kind of man cave, like something out of Steptoe and Son. It works just as well as chez Hunding in Act I of Die Walküre and is similarly naturalistic. Director Suzanne Chaundy and Bailey never set traps for their singers, unlike many sadistic creative duos before them.

Robert Macfarlane as Mime and Bradley Daley as Siegfried (photograph by Robin Halls)

Robert Macfarlane as Mime and Bradley Daley as Siegfried (photograph by Robin Halls)

This act can pall – especially the soup-making scene – but here it moved briskly. It ends with the extended scene when Siegfried forges Nothung from the fragments of Siegmund’s shattered sword. Bradley Daley – returning as Siegfried after his great success in last year’s concert version – was excellent in this thrilling scene.

Siegfried – with his endless petulance and puppydom – can be the most irritating hero in German opera. He is vicious and ungrateful towards his admittedly diabolical guardian, Mime. ‘In the end,’ as Michael Tenner writes: ‘it comes down to the question of whether Siegfried is sufficiently interesting to deserve a whole long drama virtually to himself, when we have the far more intriguing and involving figure of Wotan spending most of his time in the wings, and appearing, lightly disguised, only as the Wanderer.’ Daley negotiates these hazards with skill. His is a likeable and plausible young Siegfried.

Daley seemed to keep much in reserve during Act I – quite sensibly, for this is an immensely taxing role and many Siegfrieds come to vocal grief. Daley was especially good in the Act II scene when Siegfried – listening to Waldweben or Forest Murmurs – tries to imagine his parents and wonders if all mortal mothers perish because of their sons. Daley sat on the edge of the stage, unusually close to the audience. Here, the Ulumbarra Theatre’s peculiar intimacy really suited this affecting scene.

Robert Macfarlane returns as Mime, having sung the role last year. Mime can be an irritating character, especially if he chooses to bark at us. Interestingly, Anthony Negus, interviewed by Sophie Rashbrook for the excellent program, says: ‘I’ve always thought the problem with Act I is that we have no female voices, and it can become very wearing if the singer playing Mime just sings it all in an ugly way, or as a caricature.’

Macfarlane mostly avoids the strident pitfalls. His is not a large voice. The physical comedy is broad. His first action is to spit on his glasses, as if to announce what a boor he is. Mime – twitching and shuffling and moueing and cowering – is all over the stage. His schemes are endless, for he is every bit as ambitious as his brother, Alberich, to whom he reports.

The scene between Alberich and the Wanderer that opens Act II was memorable. These are two commanding voices: Simon Meadows and Warwick Fyfe are probably the highlights of this entire production.

The Dragon scene was simple and effective, mostly via video. Siegfried duly slays Fafner with Nothung. Best of all was the almost tender passage that follows when Fafner – now embodied as Steven Gallop – demands to know who has conquered him, to which Siegfried replies: ‘There is much that I still don’t know: / I still don’t know who I am.’ Yet the taste of Fafner’s blood enables him to understand the song of the Woodbird (Rebecca Rashleigh, on stage throughout, in good voice) and he sets off to claim the Nibelung hoard and the Tarnhelm, and thus become lord of the world.

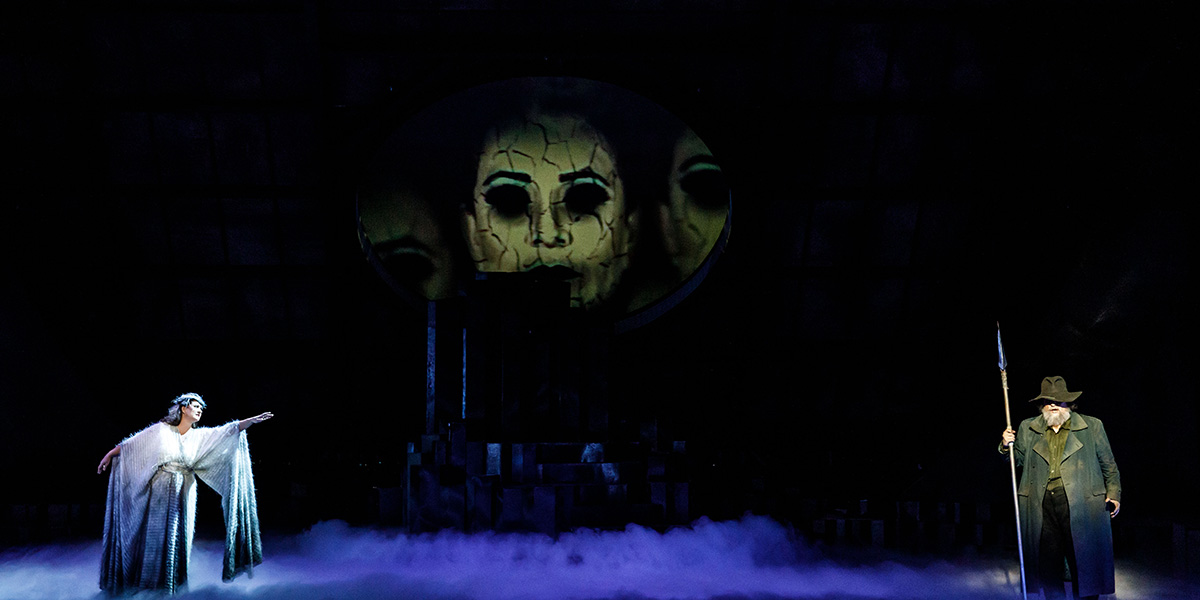

Deborah Humble as Erda and Warwick Fyfe as The Wanderer (photograph by Robin Halls)

Deborah Humble as Erda and Warwick Fyfe as The Wanderer (photograph by Robin Halls)

The Prelude to Act III – Wagner’s return to the Ring – is the most thrilling and orchestrally complex passage in the Ring. The scene that followed was momentous. Wotan awakens Erda – all-knowing, eternal woman (Ewiges Weib) – from her brooding sleep that he may now ‘gain knowledge’, as he puts it. ‘My sleep is dreaming, / my dreaming brooding, / my brooding the exercise of knowledge,’ she tells him. The deeds of men ‘becloud her mind’, and in the end she rejects the ‘stubborn, wild-spirited god’ who has disturbed her sleep.

Deborah Humble moved with grace – a bravura, almost balletic performance – and she sang magnificently. Warwick Fyfe was every bit as good.

Wotan, with his reflexive amour-propre, is incapable of submitting to anyone: that is his true curse. In his final scene, Wotan seeks to bar Siegfried’s way, but his authority is literally shattered and he surrenders the stage in one of the forlornest exits of all.

The final scene in the opera, when Siegfried discovers the sleeping Brünnhilde, who eventually responds to him, offers some of the most exalted music in the Ring. Daley and Antoinette Halloran negotiated this long, climactic duet with power and artistry.

Anthony Negus first conducted Siegfried in 1985 – a long association. This is perhaps Wagner’s most radiantly symphonic score. Here, supremely, Wagner uses the orchestra as the protagonist of the drama. We recall how well the orchestra performed last year under Negus’s guidance. On this occasion, however, the results were much less happy. There were many infelicities – not just in the brass. This was not one of the orchestra’s finest nights.

Bradley Daley as Siegfried and Antoinette Halloran as Brunnhilde (photograph by Robin Halls)

Bradley Daley as Siegfried and Antoinette Halloran as Brunnhilde (photograph by Robin Halls)

Götterdämmerung – the last opera in Der Ring des Nibelungen – opens with a subtle, doom-laden modification to the chords to which Brünnhilde had finally stirred in Act III of Siegfried. The Prologue and Act I are then performed together – two hours in all, though on this occasion it felt like half that time, such was the dramatic fervour on stage.

First came the Erda’s daughters the Norns (Dimity Shepherd, Jordan Khaler, Eleanor Greenwood), weavers of the rope of fate on which the world’s future will depend. The portentous rope can be a drag, but here it was stealthily deployed as the Norns proceeded to tell us much about Wotan. By now, members of the audience may have thought they knew everything there was to know about the ruler of the subjugated world, but Wagner once again, in his retrospective zeal, surprises us. What a relentless teller he is: imagine his table-talk at Wahnfried, with Cosima at his feet, noting it all down in her diary.

Utimately, the Norns realise that their time is over, their wisdom at an end. ‘Eternal knowledge has ended,’ they lament. When the fateful rope snaps, they join Erda in exhausted, timeless sleep. Done well, as here, this is a scene of considerable pathos; Chaundy directs these three singer-actors with her customary assurance. Hers is such a sensible, elemental conception of the Ring. It enables her singers to ‘stand and deliver’ in the best sense, unencumbered by otiose directorial whimsies. Everything makes sense, possibly for the first time in the history of the Ring.

Of the Norns – Eleanor Greenwood (who sang Ortlinde in Die Walküre) – stood out. Greenwood, who recently transitioned from mezzo soprano to soprano, has an enormous voice. Just last week she won the 2023 Opera Awards. Those attending the third cycle of the Ring will have an opportunity to hear Greenwood as Sieglinde.

We must wait until the second scene of the Prologue to meet the post-coital lovers on their rock. The orchestral interlude was superb, conveying the grandeur of this music. From the outset, the orchestra was in excellent form after the serial lapses of Friday night. It was quite a transformation. Maestro Negus drew impassioned playing all night, with a rich overlay of the many leitmotifs (there are more than sixty in all) – those melodic moments of being, as Wagner called them. Negus and the orchestra deserved their huge ovation at the end of the performance.

This is a new production, of course, like Siegfried. In Act I, we were keen to see what Bailey would make of the castle of the Gibichungs. In fact it rather resembles an expensive pile in Portsea, with its red carpet, its garish modern sculpture, its diaphanous curtains, and the inevitable sea view. This felt just right for the three arrivistes: Gunther and his sister, Gutrune, and Hagen, their half-brother, son of Alberich. The two men, keen to enhance the Firm’s reputation by orchestrating a prominent marriage, settle on Siegfried as Gutrune’s groom, carnally distracted though he is.

Steven Gallop – our Hagen – sang with considerable power and dramatic effect. Christopher Hillier (Gunther), beautifully costumed again by Harriet Oxley (an expressive green moiré suit just right for this innocuous plaything of Hagen’s) was similarly strong-voiced. Kerry Gill, as the winsome Gutrune, was barely audible.

Just when you thought this ensemble could not produce another duet to rival those that have preceded it – Brünnhilde and Wotan’s Farewell, Erda and the Wanderer in Siegfried, and many others – along came Waltraute in Scene Two. Visiting Brünnhilde on her rock, she tells of Wotan’s catatonic state and implores her sister to return the gold to the Rhinemaidens. Brünnhilde – exultant in love – refuses. The Ring is her salvation. Waltraute can tell their father that Brünnhilde will never part with the gold – will never relinquish love.

Once again, as in Erda’s brief interdiction in Rheingold and her seismic quarrel with Wotan in Siegfried, Deborah Humble revealed herself to be an artist at the height of her dramatic and vocal powers. Hard it is to recall a more impassioned account of this scene, which can pass unnoticed in lesser hands. Humble, not holding back, brought out the fiery best in Halloran. This was grand singing and acting that shook the house – unforgettable theatre that once again, as so often in this production, seemed to transcend the form. Fortunate we are to have heard Humble in these two roles (ones she also performed in Opera Australia’s Ring in 2013).

Act II begins memorably, with Alberich’s final appearance as Hagen sleeps, spear in hand. To the gravest music, Alberich (the self-declared ‘mirthless, much wronged dwarf’) extracts a promise from his son to kill Siegfried and regain the Ring. ‘Hasse die Frohen,’ Alberich beseeches him – ‘Hate the happy’. (Now and then, among Wagner’s ponderous libretti, there are lines of which any writer would be proud.) Simon Meadows’s three Methodish turns as Alberich – wound-up, splayed fingers, twitching and writhing, unbelievably tense – have been vocal and dramatic highlights of the production. How he slithered onto the stage at the start of this scene.

Chris Hillier as Gunther and Antoinette Halloran as Brunnhilde and Company (photograph by Robin Halls)

Chris Hillier as Gunther and Antoinette Halloran as Brunnhilde and Company (photograph by Robin Halls)

Then we had the crude and abrupt conceit when Siegfried is drugged into betraying Brünnhilde and goes on to arrange her proxy rape and abduction. Brünnhilde’s devastation when she is dragged to the castle of the Gibichungs and realises that Siegfried is about to marry Gutrune is always distressing to watch. Here, Halloran was at her most magnetic (those flashing eyes helped), shock and incredulity soon giving way to indignation and murderous intent. She allies herself with the odious Hagen, revealing the one physical weakness in Siegfried’s repertoire that Hagen can exploit to avenge her.

When I reviewed the Opera Australia /Neil Armfield production of Der Ring in 2016, I noted that in Götterdämmerung Wagner begins to do all manner of things that he had hitherto resisted in the Ring. Finally, a chorus is introduced, to rousing effect in Hagen’s bereted Blackshirts’ two mighty choruses. Act II ends with a distinctly Verdian revenge trio between the wrathful Brünnhilde and the scheming half-brothers.

Thus, finally, Act III, and the conclusion of Der Ring. Initially, it was to end quite differently, with Brünnhilde leading Siegfried to Valhalla. But then Wagner drew on Erda – ‘All that is – ends; a gloomy day dawns on the gods.’ He decided, controversially, that the gods must perish, even though the Ring was to be returned to the Rhine.

After the melodic scene when the Rhinemaidens make a last attempt to prise the Ring from Siegfried, and after the hunting party when Siegfried indulges in yet another lengthy narrative recapitulation, Hagen dispatches him with his spear and Siegfried (undrugged now) recalls how he awakened Brünnhilde from sleep. All day – all evening it seemed – Bradley Daley acted with energy and involvement, just as he sang with great accuracy and power. It was a memorable performance in this toughest of roles in the German tenor repertoire.

The Funeral Music that followed was beautifully executed. No supernumeraries trooped on to dispose of the corpse. Siegfried – private in death – lay on his own as the stirring music unfolded.

Antoinette Halloran as Brunnhilde (photograph by Robin Halls)

Antoinette Halloran as Brunnhilde (photograph by Robin Halls)

Then Brünnhilde presides in an epic scene of expiation and self-abnegation. Here, Antoinette Halloran was at her most impressive. What a vivid and agile singer-actor she is. There was some fine soft singing in the lower register, but the high notes were always there – steely, ringing, fearless. (Halloran – with her big, bold, serviceable voice – reminds me of Eva Marton, Bernard Haitink’s Brünnhilde in his estimable EMI Ring.)

Brünnhilde’s blessing for Wotan (‘Ruhe, ruhe, du Gott’), one of the most affecting blessings in all opera, was beautifully sung. How keenly Wagner’s beloved Valkyrie realises that the Ring is the cause of all misfortunes. Then Brünnhilde lay by Siegfried as the flames rose in our imagination and as violins played the theme last heard in Act II of Die Walküre – ‘Redemption through love’.

Much has been written about the true meaning of the Ring – not all of it tosh. Bernard Shaw, in The Perfect Wagnerite (1898), is the work’s most brilliant and tendentious champion. In closing, though, I will turn to one of the shrewdest and most searching commentators on the Ring, Michael Tanner, whose short book Wagner (1996) I encourage newcomers to explore:

So what is the Ring really about? For one thing, it seems to be about the power of the Ring, as announced in the opening scene, since no one who gets it derives any benefit from it … Most people, it seems, spend the larger part of their lives pointlessly, doing nothing in particular or pursuing goals which will give them no satisfaction. The Ring is best seen, despite the Rhinemaiden’s ill-advised claims on its behalf, as the image of what almost everyone seeks but either fails to find, or regrets it if they do … The Ring is, and only partly on account of its dimensions, Wagner’s most sustained attempt to portray the complexities of life, not omitting anything which plays a vital role. Since he was an extraordinarily complex person, anyway, his preparedness to express, or rather insistence on not suppressing, any element in his experience and awareness was bound to result in something that is, in its endlessly fascinating respects, untidy. Since he was among the greatest composers, more interested in the symphonic than the operatic tradition which he inherited, the Ring’s musical structure was bound to be, in various ways, at odds with its dramatic content, seeming to give the latter a coherence which in its honesty it can’t possess.

When Wagner finished writing Götterdämmerung, he noted the date and added: ‘I shall say no more.’ But never trust an artist! After all, Wagner hadn’t tackled Christianity yet. Parsifal in Bendigo, perhaps?

First, though, let’s congratulate Melbourne Opera for what it has achieved – against the odds – and hope that it will revive this production in a few years’ time. Vocally and conceptually, it surely ranks as the finest modern Ring seen in Australia.

Der Ring Des Nibelungen (Melbourne Opera) continues at the Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo. There are two more full cycles, beginning on Good Friday. The season ends on 30 April 2023.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.