Commentary

The question is probably all wrong. How can an American – well, an Egyptian-born American, if hyphenate we must – pronounce life on Australia? I came to the Antipodes late in my life, drawn to the Pacific, that great wink of eternity, Melville called it, drawn to horizons more than to origins. I made friends and became in Australia a wintry celebrant.

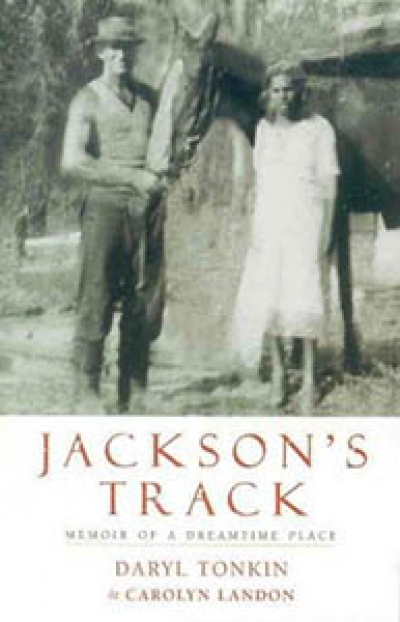

... (read more)Jackson's Track: Memoir of a Dreamtime place by Daryl Tonkin and Carolyn Landon

I first heard of Martin Boyd at a dinner party in the Cotswolds in the early 1980s. At the time I was adapting a novel by Rosamond Lehmann for the BBC, an enterprise with unexpected hazards, as Rosamond was very much alive and keen to be involved in the process. I had just begun my account of driving to the studio with Rosamond – a formidable and still beautiful woman, who relied on God to solve her parking problems – when the guest of honour, sitting opposite me, interrupted.

... (read more)During that torrid season when I was trying to place my forever unplaced and ultra-controversial novel Complicity (now called The Blood Judge, with good reason) one well-known and basically sane Fiction Editor comforted me. ‘You see, we don’t just publish a book, we have to market a personality.’ He later became even more famous for trying to market a white author (whom he had never met) as a black one.

... (read more)The last thing a highbrow hack needs is to find himself in a sustained bout of controversy with a blockbusting writer from the other side of the tracks. A few weeks ago at the Melbourne Writers Festival, I found myself a participant in a discussion about reviewing (and whether the critic was a friend or a foe) which rapidly turned into a sustained accusation on the part of the bestselling novelist Bryce Courtenay that I and the chairman of the panel, Professor Peter Pierce of James Cook University, were literary snobs with no conception of any popular genres in general and no apprehension of the critical injustices (and personal pain) which Courtenay in particular was subjected to by us and all our ilk.

... (read more)A player of the calibre of John McEnroe constantly thrills his audience with strokes so perfectly timed that they appear effortless and lethal – and it is this combination which regularly amazes spectators. They may at times sense that what contributes so effectively to this timing is an early preparation of his strokes. He seems always already ready. It is, I suspect, only on fewer occasions that an admiring audience can see, and appreciate, what lies behind that: an ability, seemingly an uncanny one, to anticipate the play of the opponent. So uncanny sometimes that spectators come close to laughing, embarrassingly, at the supposed ‘luck’ of the player – to manage even to ‘get the racket at’ some extremely difficult or unexpected shot by the opponent, but then perchance to hit it for a winner. But the wise audience ‘knows’ that only the exceptional player has such ‘luck’ and has it so often. It is uncanny.

... (read more)I opened up my last issue of ABR to see my photograph. It’s there because I was mentioned at a conference at La Trobe as evidence of an ascendant antiintellectualism. I suspect my new reputation as a villain on the black hat side of the Culture Wars has a lot to do with my play, Dead White Males, or, more accurately, the fact that the play proved popular with audiences. Dead White Males satirised the dominant theology of the humanities, variously called postmodernism, post-structuralism, deconstructionism, social constructionism or what you will.

... (read more)The Australian literary scene has always been more depressing that it is lively, especially when critics and writers are quick to display their battle scars in public places where oftentimes the debate hardly rises above fawning or fighting. The walking wounded are encouraged to endure. This is about the only encouragement extant. I remember the Simpson episode, not O.J. but Bart, who arrived in Australia for a kick up the bum. Perhaps the emulation of Britain has reached such an unconscious proportion that no ground can be explored beyond the grid bounded by Grub Street and Fleet Street, where youngsters need to be caned for reasons more prurient than wise, and where small ponds become the breeding pools for goldfish pretending to be piranhas dishing up more of the same stew. Thus, British writing, apart from its internationalists, hath come to this sad pass. Or where, given the brashness of being itself a young nation unused to finesse, Australia’s grand ideals end up as populist opinion – a talkback republic of letters irrelevant to its real enemies.

... (read more)‘Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.’

Can I begin like that? It’s risky, and contentious, and will probably come back at me. But it’s no less a stupid comment for all that. In my experience it is usually the ones who say it who are the ones who can’t.

... (read more)Some years ago the poet John Forbes was addressing himself to that national monument, Les Murray, and he had occasion to remark, ‘The trouble with vernacular republics is that they presuppose that the kingdom of correct usage is elsewhere.’ It was, I suppose, designed to highlight the fact that the homespun qualities of the Bard from Bunyah were dependent on an awareness of the metropolitan style Murray willed himself to transgress and that there was an inverted dandiness, if not a pedantry, in all that Boeotian ballyhoo. It does not seem to me a remotely fair remark but it is a good epigram notwithstanding and it takes on a range of meanings depending on what light you look at it in. Presumably Forbes thought, or feigned to think, that Murray’s poetic demotic was a variation on that Colonial Strut which is, in fact, a version of the Cultural Cringe. In any case his words came into my head the other day when I was reading Simon During’s new Oxford monograph about Patrick White.

... (read more)