Commentary

Modern Australians live of course in a concourse or babble of discourses. We make our way through the bubble-and-squeak of chopped-up value systems. There is no tall hierarchy of speakings, no league ladder. Nor is there anything as redgum-solid as permanence; if anything, transience is taken as proof of the genuine.

... (read more)Thea Astley’s first novel, Girl with A Monkey (1958), signalled the arrival of a writer with a distinctive style. Astley believes that Angus and Robertson accepted the book, although it would not be a money-spinner like the work of their bestsellers, Frank Clune and Ion Idriess, because their editor Beatrice Davis took the initiative in encouraging ‘a different form of writing from the Bulletin school’. The plain Bulletin style, a consciously shaped style representing ‘natural’ narrative, was still the norm in Australian writing in the 1950s, although that decade also saw the publication of stylistically evocative novels like Patrick White’s The Tree of Man and Voss, Hal Porter’s A Handful of Pennies, Martin Boyd’s The Cardboard Crown, A Difficult Young Man, and Outbreak of Love, and Randolph Stow’s The Merry-Go-Round in the Sea, A Haunted Land, The Bystander, and To the Islands.

... (read more)Publishers are like invisible ink. Their imprint is in the mysterious appearance of books on shelves. This explains their obsession with crime novels.

To some authors they appear as good fairies, to others the Brothers Grimm. Publishers can be blamed for pages that fall out (Look ma, a self-exploding paperback!), for a book’s non-appearance at a country town called Ulmere. For appearing too early or too late for review. For a book being reviewed badly, and thus its non-appearance – in shops, newspapers and prized shortlistings.

As an author, it’s good therapy to blame someone and there’s nothing more cleansing than to blame a publisher. I know, because I’ve done it myself. A literary absolution feels good the whole day through.

... (read more)If before the 1890s, books had been judged by their dust jackets, most would have been considered uniformly dull, or indecently attired. Dust jackets appeared first in 1833 to protect the recently introduced cloth casings as they made their progress from printery to publisher’s warehouse, on to booksellers and then to library shelves, at which stage the wrappings were usually thrown away. Those earliest dust jackets could be blank or printed with the title as well as the names of the author and publisher on the front, or notices about other volumes on the back panel.

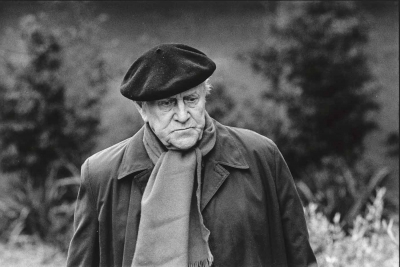

... (read more)He described himself as a ‘no-hoper’ (he died in a mental hospital in the poverty of his poetry and Catholic faith). These days, the label ‘a poet’s poet’ is sufficient to scare off anyone interested in approaching a body of work that is both substantial and challenging. With the publication of this annotated collection, containing most of Webb’s known poetry and extracts from his verse dramas, it is just a little dispiriting to see Webb’s work acquire a whiff of canonical sanctity. A short, cautious introduction by the editors Michael Griffith and James McGlade concludes with the respectful praises of five eminent Australian poets, as if a show of hands from the panel of distinguished experts were enough to explain anything of the enigma of Frank Webb to someone coming across his work for the first time. I think he deserves more. In an age where packaging plays such a conspicuous role, it is time to rescue Webb from the shrine of Tradition and to make an effort towards attracting new readers to a poet who magnificently defies idle curiosity.

... (read more)What a tragedy it would have been if after ten years the French had decided to let de Brunhoff’s masterworks fall by the wayside; if the Americans had shelved Sendak in favour of something more ‘current’, or the English publishers of Beatrice Potter had let her little masterpieces languish without giving them a kick-start every decade or so!

... (read more)Rudyard Kipling could not understand why his cheque account was so much in credit. The answer was that the tradespeople in his village were selling his signature to autograph collectors for more than they would have received by presenting Kipling’s cheques to the bank.

... (read more)‘No,’ Ania Walwicz said at the Melbourne Festival when asked if she was an ethnic writer, ‘I’m a fat writer.’ We laughed and applauded.

The multicultural professionals, however, may not let her (or Tess Lyssiotis) off the hook so easily. I have in mind that small but eloquent band of people, usually from institutions, who actually have a vested interest in keeping constructs like Anglo-Celtic/non-Anglo-Celtic, English-speaking background/non-English-speaking background alive and functional.

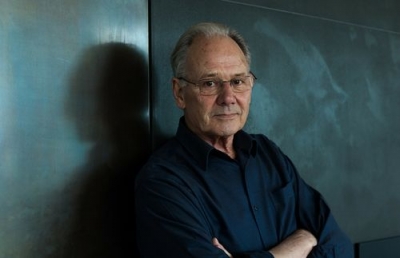

... (read more)I met Patrick White first in 1965. Reduced to 1.9s.6d, he was lying, in an American edition of Riders in the Chariot, on a sale table at Finney Isles department store in Brisbane. So much has changed. Today, we would talk of remainders; the shop has been taken over by David Jones which has in turn been taken over by Adelaide Steamship which later bought up Grace Bros; prices are now given in dollar and cents.

... (read more)Writers and readers, it seems to me, are often driven by a need to confess. Everything. Not just sins. But the lot. To confess in the original secular sense of this word; to utter, to declare (ourselves, that is), to disclose and uncover what lies hidden within us. If I’d not been a writer, I used to think I’d like to have been an archaeologist. It’s only recently I’ve located the connection between writing fiction and archaeology. Historians and biographers are probably just as confessional in their work as writers of declared fictions. But they are undoubtedly able to more easily disguise this because they are accountable to the objective – to outcrops of unrelocatable facts along the way, that is.

... (read more)