Non Fiction

Cactus Pear for My Beloved: A family story from Gaza by Samah Sabawi

Majnoon, Arabic for ‘madness’, looms over the life of Abdul Karim Sabawi, whose story is the central thread in Samah Sabawi’s 2025 Stella-shortlisted offering, Cactus Pear for My Beloved. The madness first takes form as the town lunatic, who terrorises the boy and his mother at the local well with concocted Quranic incantations. Thereafter, the majnoon casts fear from the sky, his ‘senseless and ruthless violence’ manifesting as Israeli aeroplanes that shadow Karim’s childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood in Gaza, Palestine. Born in 1942, Karim witnesses Al Nakba:

... (read more)In the quick-scroll world of soundbites and ‘shorts’, academic professionals must pack their expertise into a concise form, writing ever shorter narratives. Sheila Fitzpatrick, an eminent Australian scholar of everything Soviet, delivers in shorthand. Her little book focuses on a single aspect of one person’s life with Joseph Stalin’s death.

... (read more)A Fractured Liberation: Korea under US occupation by Kornel Chang

In the late hours of 3 December 2024 South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law in response to what he claimed was a ‘legislative dictatorship’ directed by ‘anti-state forces’. In shocking scenes broadcast around the world, citizens took to the streets in protest and mobilised army units defied orders to suppress dissent. Meanwhile, 190 legislators from both parties forced their way into the National Assembly to unanimously vote down the martial law declaration. It was rescinded just hours later, and the disgraced president was subsequently impeached and unceremoniously removed from office.

... (read more)The Captains’ Coup: From dictatorship to democracy in Portugal (1974-1976) by Wilfred Burchett and edited by Daniela F. Melo and Timothy D. Walker

More than a decade ago, two academics browsing in an antiquarian bookshop in Lisbon stumbled across a Portuguese language account of the 1974 Captains’ Coup by Wilfred Burchett. A little digging revealed that while the volume had been translated into Italian and Spanish in the year of its publication, with a Japanese edition appearing the year afterwards, no English language edition had ever been produced. Indeed, nobody seemed to know where the original manuscript might be found. A chance encounter and a helpful librarian located the original typescript in the Burchett papers at the National Library of Australia in Canberra. While this detective story makes for an entertaining preface, it is telling that having tracked down and meticulously prepared the manuscript it then took the editors more than ten years to find a publisher for the first English language edition of The Captains’ Coup.

... (read more)Ferryman: The life and deathwork of Ephraim Finch by Katia Ariel

On weekday mornings in the 1950s a teenager called Geoffrey William Finch would ride his Malvern Star through Sydney’s Rookwood cemetery on the way to his carpentry job. Cutting across fields of headstones, he talked incessantly. When, several decades later, Katia Ariel asks who he was speaking to, Finch pauses, closes his eyes and then, ‘with a boyish smile playing on his bearded face’, explains that he was ‘talking to God’.

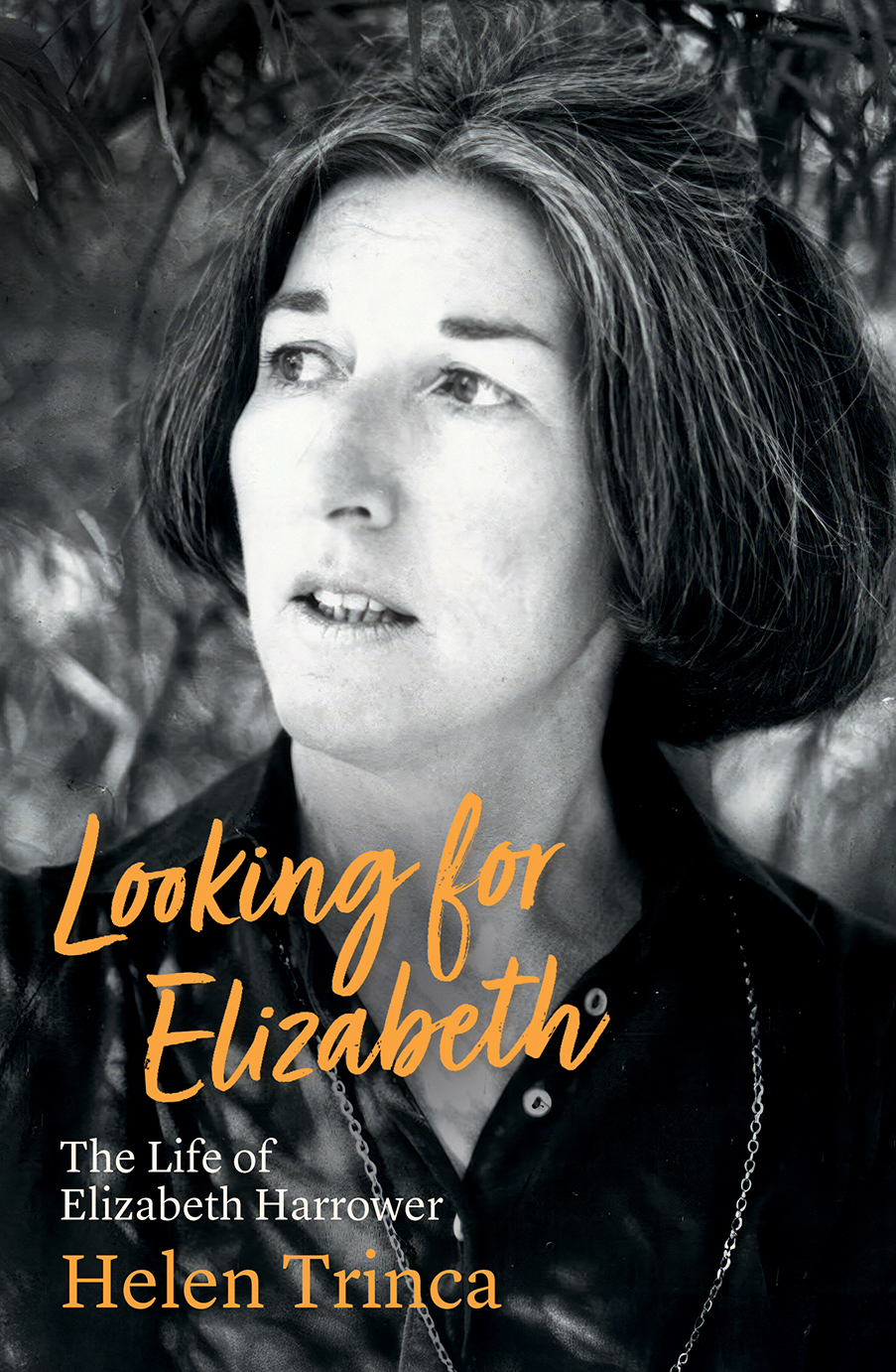

... (read more)Looking for Elizabeth by Helen Trinca & Elizabeth Harrower by Susan Wyndham

That Elizabeth Harrower should merit not one but two biographies would have both surprised and pleased her. That the biographies would be published within months of each other, by two Sydney writers and journalists, using much the same source material, would have intrigued her, as it did me. I don’t know Helen Trinca or Susan Wyndham, or who had the idea first, or anything of the anxiety they must have felt at being pipped at the post, or of any rivalry for sources and access to people or documents, but the two books arrived on my desk together.

... (read more)Part memoir, part manifesto, part ‘moral reckoning’, Ittay Flescher’s The Holy and the Broken opens with a tribute to Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah’. Flescher names Cohen’s timeless ballad Jerusalem’s unofficial anthem, infused as it is with Biblical allegory and, at times, a kind of despair-filled nihilism. Whereas Cohen imagined the Hebrew liturgical expression as either holy or broken, depending on the inclinations of those who heard it, for Flescher, his own newly adopted home of Jerusalem is both holy and broken at the same time. It is Flescher’s fervent wish, and the mission of his book, that the city’s diverse inhabitants come together to ‘mend what is broken and build a future that honours the holy aspirations of all of us who call this land home’.

... (read more)Living in Tin: The Bungalow, Alice Springs, 1914-1929 by Linda Wells

The ‘bungalow’ of Living in Tin’s subtitle was a rough tin shed, erected in Mpwartne (Alice Springs) in 1914 to house Aboriginal children of mixed descent. Described by one observer as ‘a place of squalid horror’, it was managed first by Arabana woman Topsy Smith, and then placed under the supervision of a white matron, Ida Standley. The two women ran the Bungalow until 1929 but the institution survived until 1942. At least one hundred children were housed in the Bungalow over its lifetime, sleeping on the dirt floor of one room with no doors or windows, provided with meagre rations and only the most basic education.

... (read more)Fathering: An Australian history by Alistair Thomson, John Murphy, Kate Murphy, and Jonny Bell, with Jill Barnard

We have had histories of Australian motherhood for decades. Fathers feature – sometimes as villains – in some of our best loved fiction: D’Arcy Niland’s The Shiralee (1955), George Johnston’s My Brother Jack (1964), and Don Charlwood’s All the Green Year (1965) spring to mind. Rounded portraits of fathers have figured in memoir and autobiography. Examples by Germaine Greer, Manning Clark, Raimond Gaita, and Biff Ward stand out. But not so in works of history, where there is a strange silence.

... (read more)The African Revolution: A history of the long nineteenth century by Richard Reid

Richard Reid’s tour de force begins with the story of a single road that ‘ran from the Indian Ocean coast, ascending the lightly wooded, elevated plateau of central-east Africa, through the small but perfectly positioned chiefdom of Unyanyembe, and then onward to the west until it reached Lake Tanganyika’.

... (read more)