Non Fiction

I was weaned on Blackadder. It was a series that hit its comedy straps when Ben Elton came on board for the 1986 second season to begin his immensely fruitful collaboration with Richard Curtis. Blackadder played a similar role in my childhood to Horrible Histories in the next generation. Its third season should probably take at least partial blame for the decades I spent studying Britain’s Georgian decades.

... (read more)Who is Kamala Harris and what does she stand for? This question animated coverage across the political spectrum during her 2024 US presidential campaign, even though she was already serving as Vice President – the first woman, the first African American, and the first Asian American to hold the office. At crucial points, Harris herself struggled to articulate her own distinctive agenda. When asked on the television talk show The View what she would have done differently from Democrat President Joe Biden over the past four years, she replied, ‘There is not a thing that comes to mind.’

... (read more)Turbulence: Australian foreign policy in the Trump era by Clinton Fernandes

This is not really a book about Australian foreign policy in the Trump era. It is, however, an attempt to chart the coordinates of President Trump’s approach to the world in his second term. It depicts Australia, not unlike most other US allies in Europe and Asia, scrambling to remain relevant to Washington as the fond and the familiar in the international system are tossed to and fro by the latest Trump hurricane. Clinton Fernandes, a former intelligence officer in the Australian army and now Professor of International and Political Studies at UNSW, is damning of the inability of successive Australian governments to explain to the Parliament or the Australian people why Australia has become, in his words, a ‘US sentinel state’, alongside the Republic of Korea and Japan. The strongest parts of the book are those which ask precisely how this state of affairs has eventuated. The questions are vital, but Fernandes knows that they are unlikely to be answered by this government.

... (read more)The Future of Truth by Werner Herzog, translated from German by Michael Hofmann

Werner Herzog is as much a poet as a storyteller, whether he is dealing in images or words. He thinks in metaphor, often extended ones, like the story of the Palermo Pig that begins his new book, The Future of Truth. His creative endeavours tend to sneak up on their final form from behind, or from sideways, pouncing in knights-move ...

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My cemetery journeys by Mariana Enríquez, translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell

Mariana Enríquez is deep in the catacombs beneath Montparnasse, the dead arranged in obedient rows. She has a plan. All she needs is a distraction, and one arrives in the form of a fainting tourist, a convenient wuss. The man falls hard – his skull thwacks the stone floor – and Enríquez seizes her moment. She slips into an alcove, works a slim bone loose, and slides it into her jacket sleeve ‘like a knife’. She strolls out past the exit guard and into the Paris daylight. ‘Is it a serious crime to steal a bone?’ she asks. ‘The catacombs are a museum, after all. But I feel so innocent!’

... (read more)In a recent interview published in ABR (November 2025), Melissa Lucashenko was asked what qualities she looks for in critics and editors. ‘Language that I can understand without needing a thesaurus,’ she responded. ‘Some points of connection, regardless of how far apart our cultures of origin might be.’ This collection of twenty non-fiction pieces written over two decades draws together a selection of keynote addresses, feature articles, radio presentations, speeches, and reviews, many previously unpublished. These pieces reflect on her career as a writer, a public intellectual, and the author of celebrated novels; Too Much Lip won the Miles Franklin Award in 2019 and her historical novel Edenglassie has won a series of prestigious awards since its publication in 2023. The pieces in this collection are also ‘personal’. The heron that features on the hardcover design of this collection gestures to Lucashenko’s totem, and we follow its tracks across the page.

... (read more)Woodside vs the Planet by Marian Wilkinson & Extractive Capitalism by Laleh Khalili

The Karratha Gas Plant sits on the Burrup Peninsula, a short drive from Dampier in the remote north-west of Western Australia. From a visitors centre perched on a hill above it, you get a spectacular view of the giant facility: stretching over two square kilometres, it is bound by the blue waters of Withnell Bay and the red rock hills of the Murujuga National Park. The first time she took in this vista, author and journalist Marian Wilkinson was stunned. ‘No image’, she writes, ‘quite captures its breathtaking size and scale.’

... (read more)Looking from the North: Australian history from the top down by Henry Reynolds

Every book is snared in the time and place in which it is written. Few authors create work that remains eternally relevant, not only because books that appear groundbreaking when published can easily date or pale with the passage of time, but for more prosaic reasons as well. Given that approximately 23,000 books are published annually in Australia alone, few survive on the shelf beyond a year or two, and even fewer become embedded in the nation’s literary imagination. Still, most authors dream of writing a ‘classic’ – even a minor classic will do.

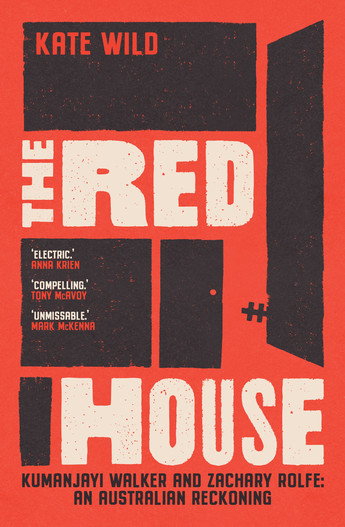

... (read more)The Red House: Kumanjayi Walker and Zachary Rolfe – an Australian reckoning by Kate Wild

It is in places like Alice Springs and remote towns like Yuendumu that the fleshy, malignant knot in the corpus of the settler-colonial nation state becomes utterly, obscenely visible. If you’re drawn to these places, you will find that regardless of who you are, at some point you will have to sit in your discomfort. In that profound culture shock, you have to accept that you are a foreigner in what you might regard as your own country.

... (read more)This week, on The ABR Podcast, Jessica Whyte reviews A Philosophy of Shame: A revolutionary emotion by Frédéric Gros. Whyte applauds the attempt to ‘revolutionise how we think about shame’ and to consider shame not simply as a retrograde emotion but ‘a resource for political struggle’.

... (read more)