Australian History

A History of the Modern Australian University by Hannah Forsyth

Hannah Forsyth, a lecturer in history at the Australian Catholic University in Sydney, begins her first chapter with the words: ‘In 1857 all of the Arts students at the University of Sydney could fit into a single photograph.’ Some neo-liberal critics of universities would argue that it has been downhill ever since. By World War II, Forsyth estimates that there were still only about 10,000 university students in Australia. Forsyth succinctly highlights the historical changes from a small élite higher education system, dominated by white male ‘god’ professors, to the current complex system, where more than one million students face major changes in higher education funding and settings.

... (read more)The Europeans in Australia: Volume 3: Nation by Alan Atkinson

On 17 January 1991, Alan Atkinson wrote to fellow historian Manning Clark to express his appreciation after reading The Puzzles of Childhood (1989) and The Quest for Grace (1990), Clark’s two volumes of autobiography. While Clark had only four months to live, Atkinson would soon begin work on The Europeans in Australia, a three-volume history of his country that would occupy him over the next twenty years. ‘I enjoyed both [the autobiographies],’ he told Clark; they ‘had a kind of subjectivity about them. It’s a remarkable style you use, which seemed to relate very much to me, so that they taught me a lot.’ Atkinson later described how he was ‘profoundly influenced’ by Clark’s work. Even more than the vast scale of Clark’s six-volume A History of Australia, it was the ‘infinite variety and open-ended stillness … of the past itself’ that affected him so intensely. Clark had shown Atkinson that the historian must ‘not just reimagine the national story but also do it in ways that ask questions about humanity itself’.

... (read more)I am a ‘Sputnik’, born in the year the Soviet satellite launched the Cold War into space. The launching by the Russians of the first artificial Earth satellite on 4 October 1957 seemed to many in the West a threatening symbol of escalating superpower rivalry. And it did unleash extreme military anxiety and triggered what became known as the Space Race. Twelve years later, in the mid-winter of 1969, I remember waking up just before midnight to watch on television as a Saturn V US rocket, wreathed in smoke and flame, inched its way off the ground at Cape Canaveral. It powered mightily against the pull of gravity and triumphed. It was beginning its journey out of Earth’s atmosphere towards the Moon.

... (read more)‘Canberra’ is a loaded term among Australians. The capital embodies the aspirations, expectations, and disappointments of a nation. It is at once a bold experiment in Australian democracy and a national source of ambivalence and derision, the unfortunate shorthand for the federal government, and a symbol of Australia’s collective disenchantment with politics. Many Australians feel they can speak for the capital and are quick to pass judgement on it. It is hotly contested ground. There is even tension between the Ngunawal, Ngarigu, and Ngambri people over who can speak for country on the Limestone Plains.

... (read more)In times of high moral outrage at the barbarism of others, it is salutary to be reminded of the state-sanctioned viciousness of Australia’s past. Simon Barnard’s A–Z of Convicts in Van Diemen’s Land does this brilliantly. Australian convict history is a crowded field, but Barnard’s detailed and vivid illustrations breathe fresh life into it. In addition to the many architectural cutaway drawings (hospitals, jails, female factories, commissariats, coalmines, shipyards, treadmills), there is a wealth of social detail: the bell-pull system for solitary confinement cells, a water canteen, cell graffiti, named dogs of the Colony, the tattoos of Francis Fitzmaurice. Indeed, it is the rupture of the human dimension into the totalising aspects of the system that surrounded convict transportation that give this book real intellectual heft. The effect is achieved through image and text, drawing on the stories of many lesser-known personalities of the period from a rich range of primary source material.

... (read more)Visions of Colonial Grandeur: John Twycross at Melbourne’s International Exhibitions by Charlotte Smith and Benjamin Thomas

Not many substantial private collections of art and decorative arts in Australia have remained intact from the nineteenth century. John Twycross (1819–89) was one of Melbourne’s early art collectors, and his collection has proved to be an exception. Twycross, lured there by the gold rush, made his money as a merchant in Melbourne in the middle of the nineteenth century. He began collecting art during the 1860s and became a major lender to the National Gallery of Victoria’s historic 1869 loan exhibition. He also spent heavily at the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880 and even made a few purchases from the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition of 1888, the year before he died. He was also a lender to the 1888 exhibition. Some 200 of the works that Twycross purchased at these exhibitions have remained together. In 2009 a descendant donated them to Museum Victoria, which is custodian of the Royal Exhibition Building.

... (read more)The German film The Lives of Others (2006) ends with a coda, set after the fall of the Berlin Wall, in which protagonist Georg Dreyman is finally allowed access to the volumes of secret files collected on him by the Stasi. Apart from the sheer number, what strikes Georg most is the utter banality of the information contained within. It is a familiar reaction among the contributors to Dirty Secrets, a collection of essays from prominent Australians on the receipt of their ASIO files.

Meredith Burgmann, who has edited these essays, is refreshingly honest as to her aims. ‘I wanted to look at the effect of spying on those who have been its targets,’ she says in her introduction. Delightedly she adds, ‘We are finally writing about them instead of them writing about us.’ The lingering outrage underpinning the book rarely subsides.

... (read more)Visiting the Neighbours: Australians in Asia by Agnieszka Sobocinska

It was timely that halfway through reading this book, I glanced up to see Clive Palmer on Q&A vowing to stand up to ‘the Chinese mongrels’. It was as if a columnist from the Bulletin circa 1895 had risen from the grave to thump a battered tub and warn us about the monster intent on destroying ‘our Australian way of life’. Images like these still lurk in the bedrock of White Australian consciousness, and Palmer’s outburst was a reminder of how readily they can be summoned.

... (read more)Prime ministers seem to value longevity, whether it is Bob Hawke relishing the fact that he served longer than John Curtin and Ben Chifley combined, or John Howard relishing that he served longer than Hawke. But no prime minister is likely to serve as long as Robert Menzies’ sixteen years as prime minister from 1949 to 1966. His record is even more impressive when his earlier term (1939–1941) is included.

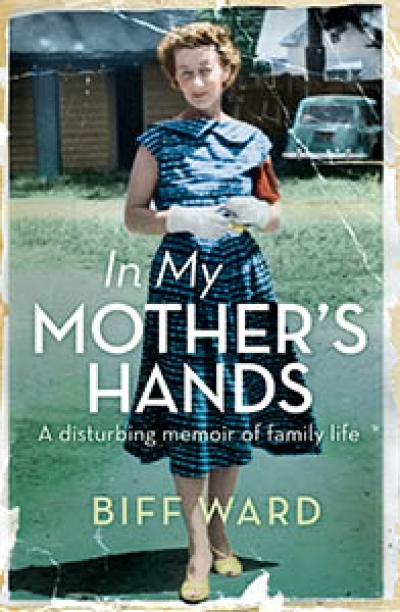

... (read more)In My Mother's Hands: A disturbing memoir of family life by Biff Ward

For anyone who has ever complained about a difficult mother, or written a memoir about one, this is a humbling book. How trivial, by comparison, our complaints seem. The subtitle promises (or threatens) a disturbing memoir, and so it is. I found it difficult to get out of my head days after reading it.

... (read more)