Australian History

Red Professor: The Cold War Life of Fred Rose by Peter Monteath and Valerie Munt

I vaguely knew about Fred Rose as somebody ASIO was after in the 1950s, a communist blackened in the Petrov case who went off to live in the German Democratic Republic. During the Cold War, that kind of boundary crossing was usually definitive. If you went over the wall, you stayed over.

Not Fred Rose. He went over the wall to the GDR, but after that he kept ...

Old Law, New Law: A Second Australian Legal Miscellany by Keith Mason

The practice of the law is about stories. The stories the parties tell to the judge, the story the judge tells back or, if you like, the judge’s review of the parties’ stories. Along the way there can be much that is frankly boring to onlookers, or indeed the parties themselves, but also drama, pathos, and humour, both intentional and the opposite. And past case ...

Awakening: Four Lives in Art by Eileen Chanin and Steven Miller

One of the few Australian-born female sculptors of the early twentieth century was a Ballarat girl, Dora Ohlfsen, who went to Berlin in 1892, at the age of twenty-three, to study music and found herself three years later in St Petersburg studying the art of the medallion. She was in Russia because she had fallen in love with the Russian-born, German-speaking Elena v ...

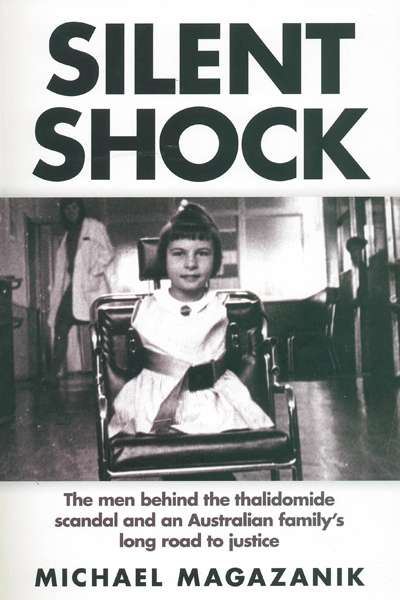

Silent Shock is an ambitious, important book. It is a work of history, a work of journalism, and a forensic exposé of hideous corporate negligence, all woven around the lives of one modest Melbourne family.

Former journalist turned lawyer Michael Magazanik was one of the dozens of lawyers, barristers, and researchers who worked on a recent class acti ...

‘I have never met an Aussie I didn’t like.’ The half-compliment was the best President Richard Nixon could muster during a restrained exchange with Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in the Oval Office in July 1973. After the turbulent build-up to this meeting, rivetingly conveyed in James Curran’s history Unholy Fury: Whitlam and Nixon at War, one almost e ...

Settler Society in the Australian Colonies: Self-Government and Imperial Culture by Angela Woollacott

Free settlement in Australia from 1788 to the 1850s is an old and favourite topic for historians in this country. It has engaged historical imagination for nearly two centuries, starting with William Charles Wentworth’s A Statistical, Historical, and Political Description of the Colony ...

‘Most history is simply lost.’ By means of a regular biographical column in the Jesuit magazine Madonna published over the past twenty-five years, Father Edmund Campion has preserved pieces of Australian personal history that might otherwise have been neglected, if not forgotten altogether. In this, the author’s second collection of biographical sketche ...

Trendyville: The Battle for Australia's inner cities by Renate Howe, David Nichols, and Graeme Davison

In the Melbourne suburb where I spent my childhood, a café was a place where ethnic men played cards and backgammon, puffed on cigarettes, and looked up from time to time to watch through the window the passing parade on the footpath outside. Now, when I return to Northcote, I am often served in hip cafés by boyish men with Ned Kelly beards and stylishly informal ...

In his essay ‘The Fiction Fields of Australia’ (1856), Frederick Sinnett conducts an inquiry ‘into the feasibility of writing Australian novels; or, to use other words, into the suitability of Australian life and scenery for the novel writers’ purpose and, secondly, into the right manner of their treatment’.

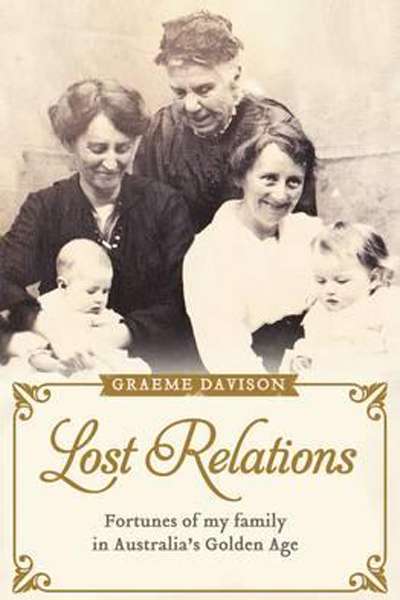

Lost Relations: Fortunes of My Family in Australia's Golden Age by Graeme Davison

Clear-eyed, unsentimental, but compassionate, with a nicely honed flair for story-telling, Graeme Davison is one of Australia’s master historians. Now Emeritus Professor of History at Monash University, his early training was in R.M. Crawford’s so-called Melbourne History School, where it was simply assumed that books would be written. Crawford’s department at ...