Arts

Film | Theatre | Art | Opera | Music | Television | Festivals

Welcome to ABR Arts, home to some of Australia's best arts journalism. We review film, theatre, opera, music, television, art exhibitions – and more. To read ABR Arts articles in full, subscribe to ABR or take out an ABR Arts subscription. Both packages give full access to our arts reviews the moment they are published online and to our extensive arts archive.

Meanwhile, the ABR Arts e-newsletter, published every second Tuesday, will keep you up-to-date as to our recent arts reviews.

Recent reviews

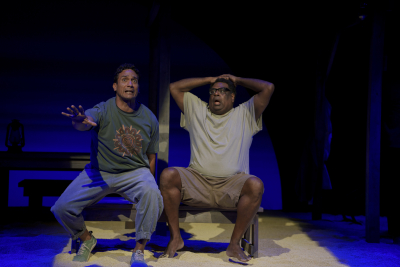

On the opening night of Dear Son at Belvoir, director and co-adaptor Isaac Drandic takes to the stage before the performance. One of the cast members is ill; on short notice, Drandic will play his role. Don’t expect a star turn, he warns.

... (read more)In the wake of publicity for Chloé Zhao’s Hamnet, an adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s award-winning novel of the same name, it gives nothing away to say that the success or otherwise of the film depends largely on the believability of its final scenes. A mother, who also happens to be the wife of William Shakespeare, has travelled to London to determine why her husband has named his newest play – a tragedy – after their recently deceased son, Hamnet. =

... (read more)After the Rain is the fifth iteration of the National Gallery of Australia’s National Indigenous Art Triennial. Delivered by celebrated Australian artist Tony Albert, it is the first to be artist led. (Brenda L. Croft had been a practicing artist for some two decades at the time she produced the 2007 inaugural Triennial, Culture Warriors, but she did so as a curator and not as an artist). Albert resists the label of curator, preferring the title Artistic Director.

... (read more)There is a particular sense of anticipation surrounding Ron Mueck’s return to Australian soil – his first since 2010. An immensely popular figurative sculptor, Mueck has built an international following through his uncanny, hyperreal sculptures of the human body. Recent exhibitions in Seoul this year at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and in 2024 at Museum Voorlinden in the Netherlands drew record crowds, as has his current touring exhibition from the Fondation Cartier in Paris. His Sydney survey, Encounter, presents just fifteen sculptures, understandable given the fact that his meticulous, labour-intensive works can take months, even years, to complete.

... (read more)To celebrate the year’s memorable plays, films, television, music, operas, dance, and exhibitions, we invited a number of arts professionals and critics to nominate their favourites.

... (read more)Arts highlights

This issue we present the best arts productions of 2025, as nominated by our critics. Across film, theatre, music, visual art, opera, dance, and television, ABR Arts continues to publish erudite, long-form, professionally edited, and independent arts reviews at a time when space for such work is diminishing across the sector. Thank you to all our critics in 2025 and to our arts readers, an enthusiastic cohort who enliven us with letters, comments, emails, and a staggering number of website hits. There is an appetite for arts criticism in this country. Our critics show that, despite the pressures facing the arts sector, and the controversies that dominated arts journalism in 2025, there remains an appetite for well-constructed and elevating productions.

... (read more)Kokuhō (★★1/2), Sunset Sunrise (★★), Chime (★★★★1/2)

The phenomenal box office success of Lee Sang-il’s Kokuhō – a sprawling epic about the friendship and rivalry between two kabuki actors – has been regarded as something of a miracle in Japan. The surprise stems from the status of kabuki: despite being a centuries-old art form of immense cultural significance, it remains neither broadly understood nor widely appreciated.

...

German baroque composer Christoph Gluck’s Orpheus & Eurydice presents several challenges for the contemporary opera director. There are only three characters, for a start. When the story opens, Orpheus/Orfeo (Iestyn Davies) has already lost his bride, Eurydice (Samantha Clarke), to a snake bite on their wedding day. She has been taken to the Underworld, to a paradise within hell.

... (read more)There was a culminative air about the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s last subscription concert for the year. Branded ‘New Worlds’ in order, no doubt, to draw attention to its inclusion of Dvořák’s beloved Symphony No.9 From the New World, at its heart was the Australian premiere of Deborah Cheetham Fraillon’s Treaty. Cheetham Fraillon’s successful five-year appointment as MSO First Nations Creative Chair draws to a close at the end of the year and Treaty appears in the shadow of the passing of the Statewide Treaty Bill 2025 (it received Royal Assent on November 13). Among other things, this bill paves the way for the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria to become a permanent, legislated body.

... (read more)