Wuthering Heights

Emerald Fennell’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ begins in darkness, with sounds that suggest sexual arousal: creaks, groans, gasps. The opening scene abruptly reveals the context: the groans come from a man swinging on the gallows. His grim climax is taking place in front of an excited, milling crowd that includes men, women, young children, a Punch and Judy show, and an appreciative nun.

The scene has both bang and whimper: sex, cruelty, punishment, and spectacle, rolled into a juicy opening sequence. There is no such event in Emily Brontë’s novel, no mention of a public execution.

Fennell has been upfront about the challenges she faced while making her film. ‘You can’t adapt a book as dense and complicated and difficult as this book,’ she said in an interview. ‘I can’t say I’m making Wuthering Heights. It’s not possible. What I can say is I’m making a version of it … There’s a version that I remembered reading that isn’t quite real. And there’s a version where I wanted stuff to happen that never happened. And so, it is Wuthering Heights and it isn’t.’

She is hardly alone in this. There have been many screen adaptations – by directors including William Wyler, Jacques Rivette, Luis Buñuel, Andrea Arnold, and Yoshishige Yoshida – and they have taken creative liberties of all kinds. What almost all the films have in common is that they stop halfway through the events of the novel, focusing on the figures of Catherine and Heathcliff and omitting their impact on subsequent generations. Fennell is no exception.

Her opening scene might suggest a few dark themes, but its depiction of a teeming crowd is misleading. The rest of the film is essentially a chamber piece, set within the confines of two contrasting households. Beyond their walls the moors loom, functioning less as landscape than gloomy, atmospheric backdrop.

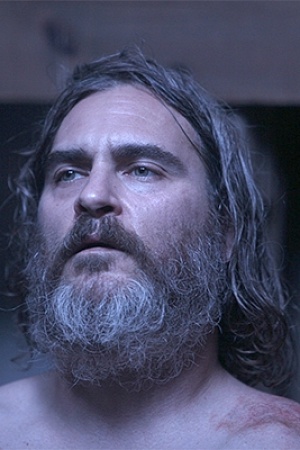

Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights (photograph courtesy of Warner Bros)

Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights (photograph courtesy of Warner Bros)

The film begins with the central characters as children. At Wuthering Heights, the property that gives the work its name, the novel’s kindly father and his resentful, vicious son are compressed into a single, ugly figure in Fennell’s version: Catherine’s father, Mr Earnshaw (Martin Clunes), who rescues a young Heathcliff (Owen Cooper) from the streets in what appears to be his only moment of goodwill. Erratic, brutal, contemptuous, a drinker and a gambler, Mr Earnshaw establishes Wuthering Heights as a grim place from the outset: a world of mud and muck and the master vomiting on the floor.

Fennell retains the figure of Nelly Dean, played as a child by Vy Nguyen and as an adult by Hong Chau. She becomes a servant in two households. In the novel, she is a significant, often unreliable narrator; Fennell makes her a meddler whose motives invite debate. She is given a new, fleetingly referenced backstory: she is the illegitimate child of a lord, whose father has paid for her to ‘disappear’.

Having established the relationship between the young Catherine (Charlotte Mellington) and Heathcliff, Fennell presents them as adults (Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi). There is a heavy-handed playfulness to their interactions, a sense of complicity, and an increasing intimacy. There is also a focus on Catherine’s simmering desire; it is as if she sees sex, metaphorically and literally, everywhere she looks, with Heathcliff as a frequent witness.

Everything changes with the arrival of newcomers to their neighbouring property, Thrushcross Grange. Catherine is as excited as any younger Bennet sister by the prospect. There is an Alice in Wonderland whimsy in the depiction of these newcomers, Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif) and his ward Isabella (Alison Oliver). We first see them dressed to the nines, taking tea in a walled garden, as Edgar listens wearily to Isabella’s account of the plot of Romeo and Juliet (a story of two households, botched communications, and romantic love and death that seems to reflect Fennell’s Wuthering Heights vision).

Edgar is almost a cipher; Fennell has little interest in him. She focuses more on Isabella, who is coy and girlish, keeps a room just for her ribbons, and has a giant dollhouse. Isabella has a crush on Catherine and makes a doll to represent her, using Catherine’s own hair. It is a somewhat heavy-handed gesture towards the living-doll fate that awaits Catherine.

Meanwhile Heathcliff has had his own glow up, with much more control over his circumstances. Having departed abruptly at the prospect of Catherine’s marriage to Edgar, he returns to Wuthering Heights as a wealthy, assured figure with a Byronic air: mad, bad, and dangerous to know. Isabella soon transfers her crush onto him. There is an intriguing scene in which Heathcliff hijacks the language of consent to reel her in, cynically laying out what he will withhold from her or subject her to.

At the heart of Wuthering Heights lies the shared, complex cruelty and devotion that binds Catherine and Heathcliff. For Elizabeth Hardwick, writing in 1972 about ‘the sustained brilliance and originality we hardly know how to account for’ in the novel, ‘[t]he peculiarity of it lies in the harshness of the characters. Cathy is as hard, careless, and destructive as Heathcliff. She too has a sadistic nature. The love the two feel for each other is a longing for an impossible completion.’

Fennell seems to want to make some form of completion possible; at least, she wants to allow them to explain themselves to one another, and she wants to see their sexual desires fulfilled. There is, however, a strangely unimaginative, stereotypical romantic depiction of their swoony assignations and adulterous trysts. Fennell might have set things up with sticky sexual metaphors and passionate avowals, but by the end she has drained the intensity, danger, madness, and cruelty inherent in these characters.

There is one other significant element Fennell has jettisoned, something that Kate Bush celebrated in her version of Wuthering Heights: a song that distils longing and possession from beyond the grave. Fennell’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ is very much about the world of physical sensations. She demonstrates no engagement with the extra-physical dimensions of Catherine and Heathcliff’s relationship, sidelining both the idea of the supernatural and the persistent intergenerational haunting that define the novel.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.