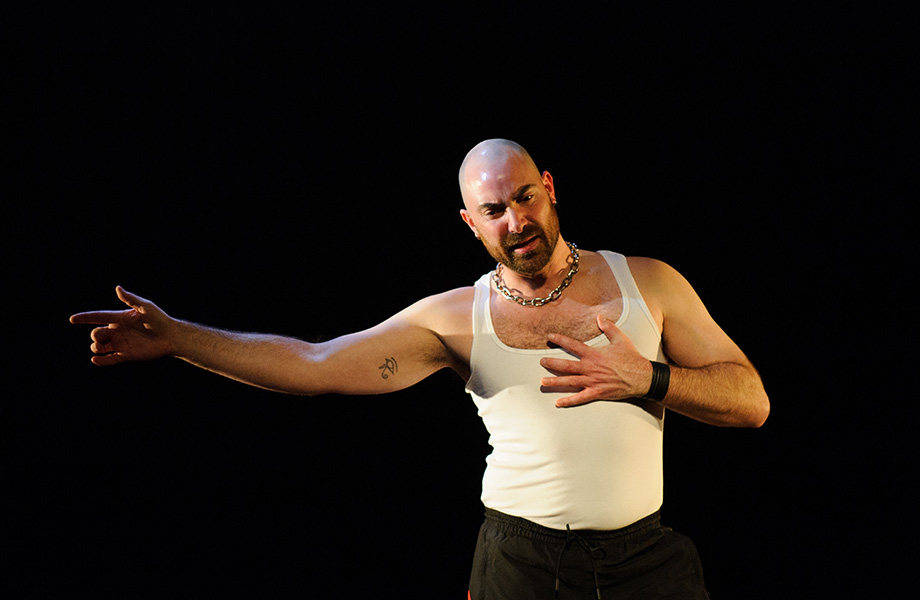

Milk and Blood

Milk and Blood are the third and fourth instalments in Benjamin Nichol’s anthology series of works for solo performers. The preceding plays, kerosene and SIRENS, similarly played as a double bill at fortyfivedownstairs a year ago and were roundly lauded (this critic, sadly, did not see them). There are threads which run through these works – in Nichol’s own words, ‘love, loneliness, violence and resilience’ – but to reduce them thus would be to take away from their distinctiveness. One might equally say that what they have in common is craft – and, indeed, heart, for both are, despite their toughness, deeply compassionate. I have seen a lot of middling and, frankly, bad high-concept work on Melbourne stages recently, after which Milk and Blood came as a relief (not a revolve in sight!). Pared back, and by turns lyrical and gritty, both plays demonstrate that ‘text-based’, playwright- rather than director-led theatre can still turn a few tricks.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.