fortyfivedownstairs

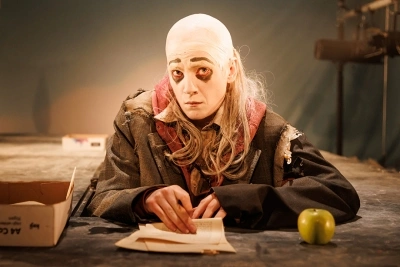

Zinnie Harris’s adaptation of Eugène Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, in this Spinning Plates production at fortyfivedownstairs, opens on a sombre wasteland setting, bathed in eerie yellow light. In a sudden blaze of colour, a raucous rabble of ordinary characters, rendered extraordinary by Dann Barber’s bold and anarchic costumes, invades the stage. The energy is starkly at odds with Jacob Battista and Dann Barber’s superbly contained and claustrophobic staging. From this heightened theatrical world – part pantomime, part circus – we brace for a wild ride.

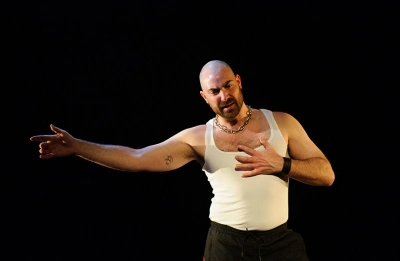

... (read more)Milk and Blood are the third and fourth instalments in Benjamin Nichol’s anthology series of works for solo performers. The preceding plays, kerosene and SIRENS, similarly played as a double bill at fortyfivedownstairs a year ago and were roundly lauded (this critic, sadly, did not see them).

... (read more)Somewhere on West 24th Street in the early 2000s, Susan Sontag asked Terry Castle whether Virginia Woolf was a ‘great genius’. Castle agreed emphatically before offering a tongue-in-cheek follow-up: ‘Do you really think Orlando is a work of genius?’ Sontag’s response was quick and admonishing. ‘“Of course not!.” she shouts, “You don’t judge a writer by her worst work! You judge her by her best work!”’

... (read more)In many ways, William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (almost certainly 1599) is a director’s rather than an actor’s play. While there have been brilliant performances associated with it – from Marlon Brando and John Gielgud to Ben Whishaw and our own Robyn Nevin – it is really the directors who make sense of it on stage, and have moulded its politics to suit the times. John Philip Kemble and William Charles Macready defined the play in the nineteenth century, with elaborately realistic sets and massive crowds, emphasising Brutus as a revolutionary figure.

... (read more)Now an octogenarian, and with more than thirty plays to her name, Caryl Churchill must be the English-speaking theatre’s nearest equivalent to a rock star of a certain age. It’s no exaggeration to say that without her plays – which, like Samuel Beckett’s, have become increasingly spare and crystalline over time, some running to as little as ten minutes – it would be hard to imagine the existence of whole generations of British playwrights, from Martin Crimp and Mark Ravenhill, to Alistair McDowell and Lucy Kirkwood.

... (read more)Is it time for Joyce’s Exiles to come in from the cold? Joyce’s only extant play has long been marginal within his oeuvre, scantly loved even by Joyce enthusiasts, and seldom produced for stage. Bloomsday in Melbourne, which has been making live theatrical adaptations of James Joyce’s prose work for some thirty years, has only got round to putting it on now, the first ever production in Victoria.

... (read more)Since its première in 1949, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman has managed to cling to cultural relevance with a vice-like grip. In 1975, New York Times critic Walter Goodman saw in its evocation of the American middle class the perfect representation of a nation-wide recession following the Vietnam War. In 1984, the play’s titular salesman, Willy Loman, became the symbol of a dwindling middle class under Ronald Reagan. And in Mike Nichol’s 2012 Broadway revival, Charles Isherwood transformed Loman into the perfect everyman for the Great Recession. That same year, Simon Stone staged an innovative adaptation of Miller’s masterpiece for Sydney’s Belvoir Theatre. It was Stone’s decision to have his actors speak in Australian accents rather than the conventional Brooklyn dialect that seemed to pry the play from its American origins.

... (read more)A solid wooden desk at centre stage is bracketed by two more placed behind it. A whiteboard is off to one side, and a pile of broken office chairs rises on a tiered platform, suggesting a throne. The rollers from five swivel chairs hang threateningly over the actors’ heads. As the audience is seated, actors in dour business suits enter and exit, checking papers with a sense of subdued activity as the ethereal strings, pads, and pizzicato melodies of Ben Keene’s sound design float through the space. Someone Blu-Tacks a pie chart split into three on the whiteboard, foreshadowing the play’s famous conceit. These pre-show touches promise an anachronistic corporate world with overtones of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil and the Time Variance Authority from Marvel’s recent Loki.

... (read more)