Allen & Unwin

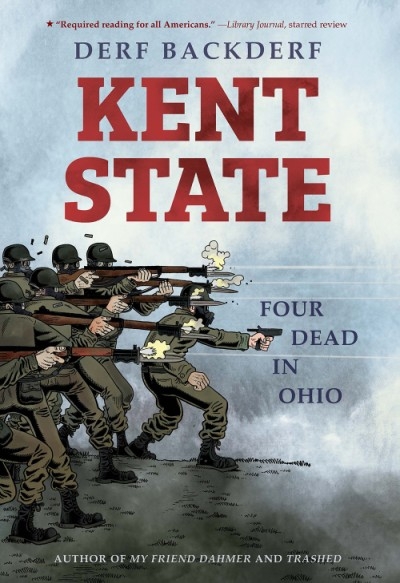

Kent State by Derf Backderf & Underground by Mirranda Burton

Paige Clark’s She Is Haunted (Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 264 pp) opens with the story ‘Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’, a title that alludes to the five stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance – that inform the rest of her début collection. Clark doesn’t explain why the narrator feels anxious about the survival of her unborn child and its father. The reader is left to assume that the prospect of too much undeserved happiness impels her to embark on a series of amusing and escalating bargains with a capricious God. That the narrator bears the losses with equanimity is indicative of the deadpan humour with which Clark deflects serious matters.

... (read more)Leaping into Waterfalls: The enigmatic Gillian Mears by Bernadette Brennan

A Life in Words: Collected writings from Gallipoli to the Melbourne Cup by Les Carlyon

Nellie: The life and loves of Dame Nellie Melba by Robert Wainwright

One of the hardest challenges for a novelist is to write a story for adults from the point of view of a child. In 1847, Charlotte Brontë set the bar high with Jane Eyre, the first novel to achieve this. The story ends when Jane is a woman but commences with the child Jane’s perspective. So effective for readers was Brontë’s ground-breaking feat that Charles Dickens decided to write Great Expectations in the voice of the child Pip, after just hearing about Jane Eyre, even before reading it. But the risks are great: creating a child narrator who knows, tells, or understands far too much for their age; dumbing down the story to fit with the character’s youth; striking the wrong notes by making the voice too childish or not childlike enough. It’s a minefield, and any novelist, especially a debutant, who pulls it off deserves praise. Thus Harper Lee, who never had to produce another book to maintain her legendary status.

... (read more)One of the hardest challenges for a novelist is to write a story for adults from the point of view of a child. In 1847, Charlotte Brontë set the bar high with Jane Eyre, the first novel to achieve this. The story ends when Jane is a woman but commences with the child Jane’s perspective. So effective for readers was Brontë’s ground-breaking feat that Charles Dickens decided to write Great Expectations in the voice of the child Pip, after just hearing about Jane Eyre, even before reading it.

... (read more)