Archive

James Macarthur by John Manning Ward & Philip Gidley King by Jonathan King & John King

by Beverley Kingston •

Exiles at Home: Australian women writers 1925–1945 by Drusilla Modjeska

by Judy Turner •

Power Conflict and Control in Australian Trade Unions edited by Kathryn Cole

by Leo Hawkins •

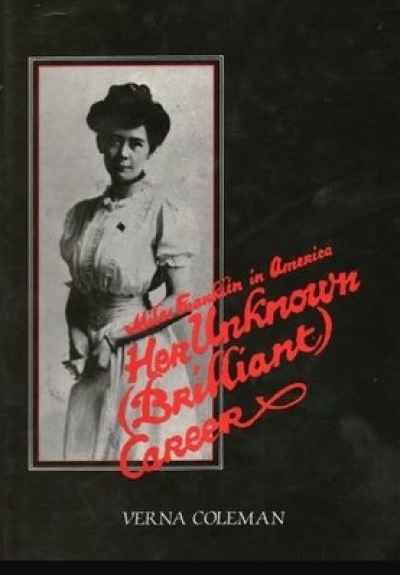

Her Unknown (Brilliant) Career: Miles Franklin in America by Verna Coleman

by Beatrice Faust •