Biography

William Lawrence Baillieu: Founder of Australia’s Greatest Business Empire by Peter Yule

by John Arnold •

Lives of the Novelists: A history of fiction in 287 Lives by John Sutherland

by James Ley •

True North: The story of Mary and Elizabeth Durack by Brenda Niall

by Susan Sheridan •

Alfred Kazin by Richard M. Cook & Alfred Kazin’s Journals edited by Richard M. Cook

by Don Anderson •

The Keats Brothers: The life of John and George by Denise Gigante

by William Christie •

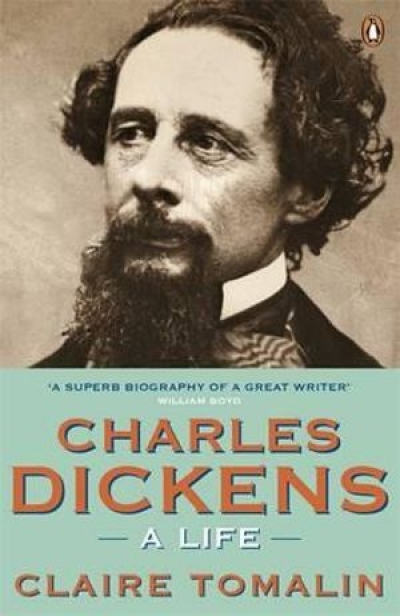

Charles Dickens by Claire Tomalin & Becoming Dickens by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

by Evelyn Juers •

Permanent Revolution: Mike Brown and the Australian avant-garde1953–97 by Richard Haese

by Peter Hill •

Women of Note: The rise of Australian women composers by Rosalind Appleby

by Jillian Graham •