Raimond Gaita

‘Dear God. Save us from those who would believe in you.’ Not long after the attack on the World Trade Centre on September 11 last year, those words were sprayed on a wall in New York. Knowing what provoked them, I sense fear of religion in them. Their wit does not dilute the fear, nor does it render its expression less unsettling. To the contrary, it makes the fear more poignant and its justification more evident.

Enough people have been murdered and tortured over the centuries in the name of religion for anyone to have good reason to fear it. Is it, therefore, yet another example of the hyperbole that overwhelmed common sense and sober judgment after September 11 to sense something new in the fear expressed in that graffiti? In part, I think it is. But the thought that makes the fear seem relatively (rather than absolutely) novel is this: perhaps the horrors of religion are not corruptions of religion, but inseparable from it. To put it less strongly, but strongly enough: though there is much in religion that condemns evils committed in its name, none of it has the authority to show that fanatics who murder and torture and dispossess people of their lands necessarily practise false religion or that they believe in false gods. At best (this thought continues), religion is a mixed bag of treasures and horrors.

... (read more)Querulous impatience has overtaken discussion of Aboriginal matters in some quarters. ‘If we apologise, they must forgive and then assimilate. Invite them to discussions about how to ameliorate their misery – the disintegration of community, the alcoholism, the glue sniffing. But they mustn’t talk “ideology”. We’ve had enough brooding over the past, heard enough about treaties and self-determination, and more than enough about genocide. It’s time to move on.’ That’s what I hear and in that tone.

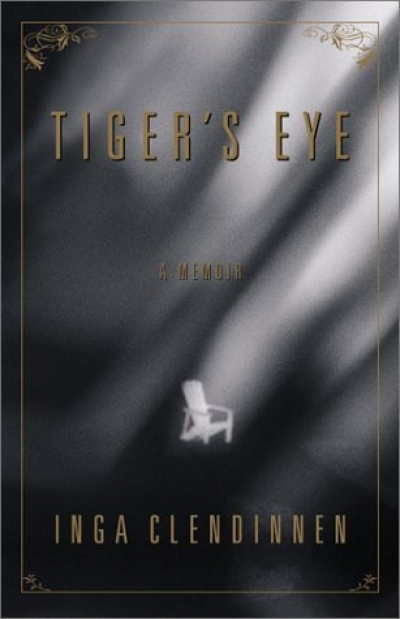

... (read more)For any editor, one of the attractions and challenges of shaping a magazine is the unexpected submission that arrives at the eleventh hour. When the author happens to be someone of the stature of Raimond Gaita, one is indeed fortunate. This month, we are pleased to be able to bring you Professor Gaita’s incisive, yet anguished, contribution to the debate about reconciliation and genocidal impulses in Australian history. His piece, entitled ‘Why the Impatience? Genocide, “Ideology” and Practical Reconciliation’, is our La Trobe University Essay for July. It takes up some of the issues raised by Inga Clendinnen in the Australian Review of Books, an essay that prompted much correspondence in the June issue of that publication.

... (read more)‘We’ve given Ayers Rock back to the Aborigines!’ Perhaps I remember those words so clearly because a friend spoke them to me over the telephone when I was in England, surprised almost daily at the reforms of the Whitlam government and at the international interest they excited. Years later I reflected on the meaning of that ‘we’. Had he said the same words to an English person, the meaning of it would have been different. Addressed to me, that ‘we’ wasn’t so much a classification that included or excluded me: it was an invitation to be part of a community whose identity was partly formed by its relation to Australia and its past and by its preparedness to accept responsibilities for what head been done to the Aborigines – at that time (before we knew about the stolen children), the taking of their lands and desecration of their sacred places. Had I thought about it, that would partly have answered the question I did ask him. ‘What does giving it back mean?’ He couldn’t say. In fact no one I asked could. No one was interested. Everyone was heartened by the generosity expressed in the gesture and enthusiastic in their hopes for a new era.

... (read more)