Archive

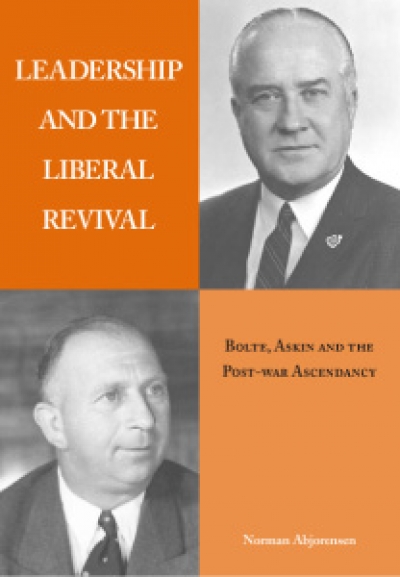

Leadership And The Liberal Revival: Bolte, Askin and the post-war ascendancy by Norman Abjorensen

by Don Aitkin •

Fifty Key Thinkers on History: Second Edition by Marnie Hughes-Warrington

by Beverley Kingston •

Political Tourists: : Travellers from Australia to the Soviet Union in the 1920s–1940s edited by Sheila Fitzpatrick and Carolyn Rasmussen

by John Thompson •

Rivals by Bill Emmott & The New Asian Hemisphere by Kishore Mahbubani

by Nick Bisley •