Australian Art

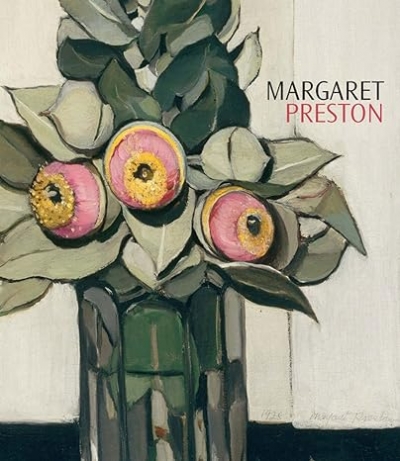

Margaret Preston by Deborah Edwards (with Rose Peel et al.) & The Prints of Margaret Preston by Roger Butler

by Damian Smith •

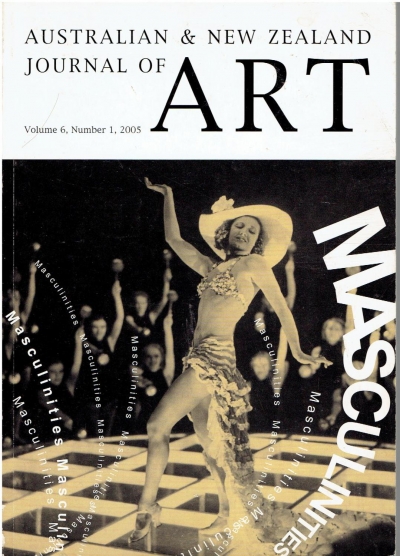

Australian & New Zealand Journal of Art: Masculinities, vol. 6, no. 1, 2005 edited by Karen Burns et al.

by Catherine Bell •

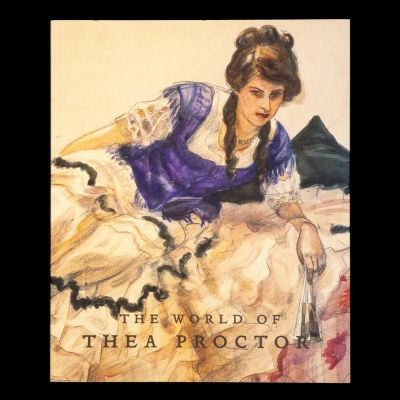

The World of Thea Proctor by Barry Humphries, Andrew Sayers, and Sarah Engledow

by Caroline Jordan •

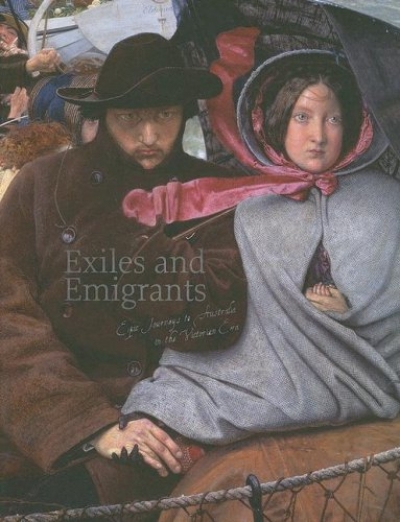

Exiles and Emigrants: Epic journeys to Australia in the Victorian era by Patricia Tryon Macdonald

by Daniel Thomas •

The Diaries of Donald Friend, Volume 3 edited by Paul Hetherington

by Ian Britain •

Through Artists’ Eyes: Australian Suburbs and their Cities, 1919-1945 by John Slater

by Daniel Thomas •

Yvonne Audette: Paintings and drawings by Christopher Heathcote, Bruce James, Gerard Vaughan and Kristy Grant

by Jason Smith •

Fred Williams: An Australian vision by Irena Zdanowicz and Stephen Coppel

by Sebastian Smee •